Opinion

A Data Analyst Looks at His Own Facebook Data

From my 10 years as an avid Facebook user, the company amassed 21 megabytes of data. What can I possibly learn from it?

Just a few clicks on Facebook’s Settings tab produced an impressive array of juicy information about my digital self. It included anything from photos and geolocation to things I liked, things I followed, things I searched for, even a history of payments made on the platform.

Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg testifying before the U.S. Senate. Photo: Reuters

Facebook's Mark Zuckerberg testifying before the U.S. Senate. Photo: Reuters The first step was to manually go over the data, a total of about 1,200 files, only 47 of them actually requiring field mapping. There were 1,150 identically-formatted files, each standing for a different person or group I ever had chatted with.

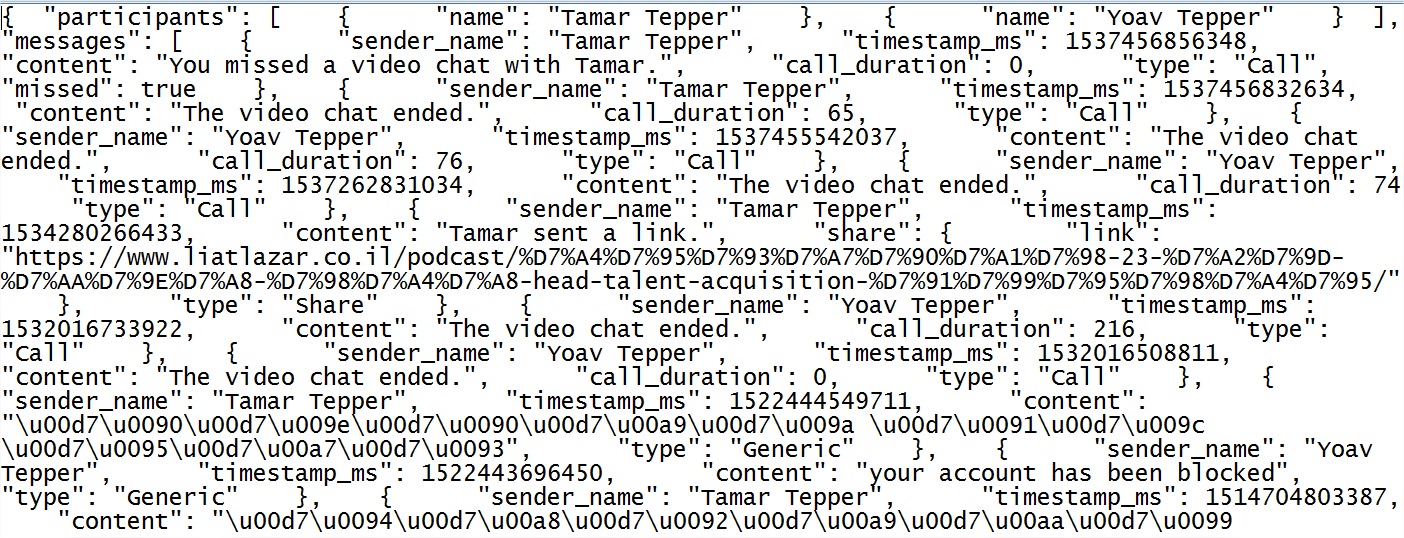

Armed with the programming language Python and data analysis software Tableau, I began to process the information. It took a few hours of code writing to standardize all the different pieces of information and turn massive amounts of raw data into coherent information. To those who are not familiar with such tasks, I had to turn this:

Image: Yoav Tepper

Image: Yoav Tepper

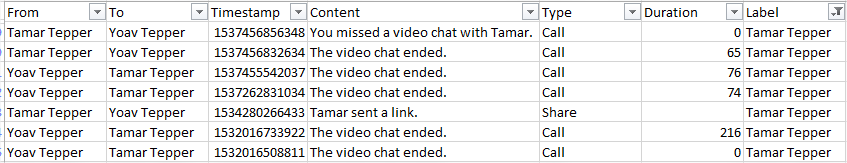

Into this:

Image: Yoav Tepper

Image: Yoav Tepper

From my 10 years as an avid Facebook user, the company amassed 21 megabytes of data, but what did it say about me?

First, I wanted to check the extent of my activity on the social network over time. I created an ordinal rating mechanism that weighs how active I was each year, taking into consideration the number of likes, chats, replies, and posts I have published. The results showed a spike in my activity in 2011, which could be attributed to the amount of free time I had, having just finished high-school.

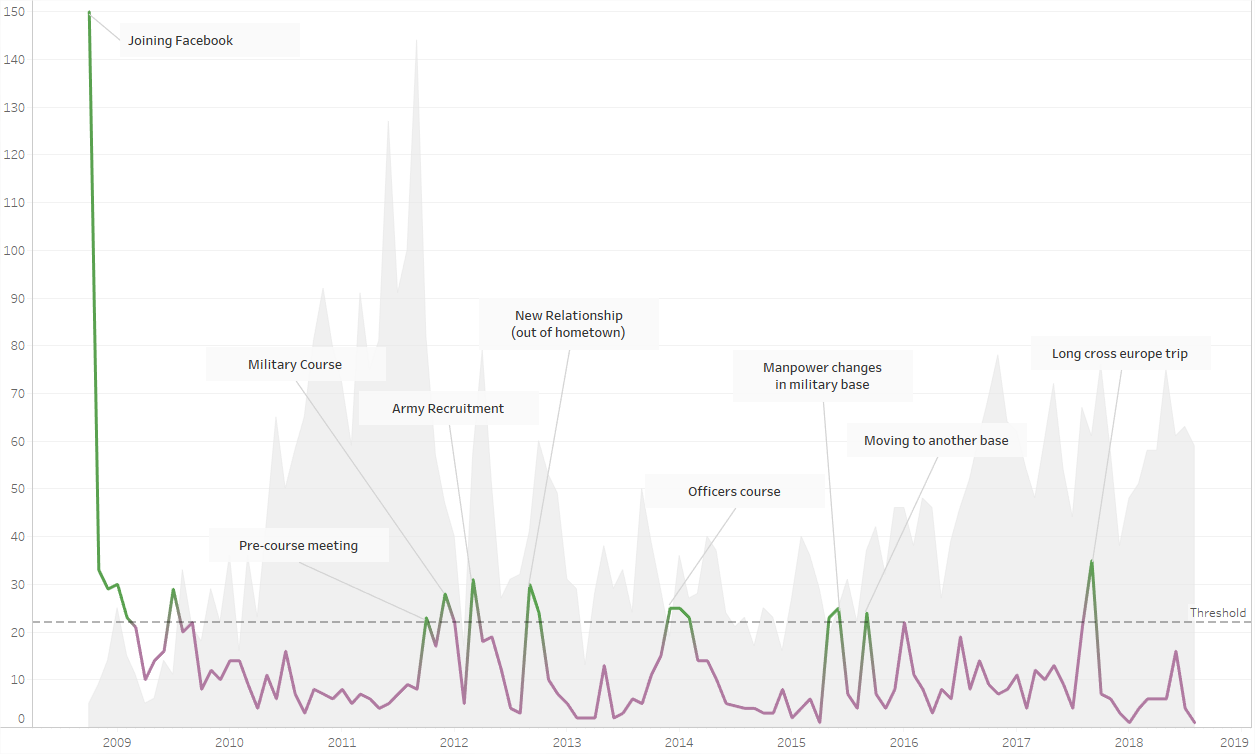

Today, I have about 1,500 Facebook friends. Over the last decade, I have added an average of 12.5 friends each month. To focus my exploration, I decided to set the number 23 added friends or more to defines a "highly social month." I then went on to try and see if these months correlated with life-events outside of the social network.

Image: Yoav Tepper

Image: Yoav Tepper

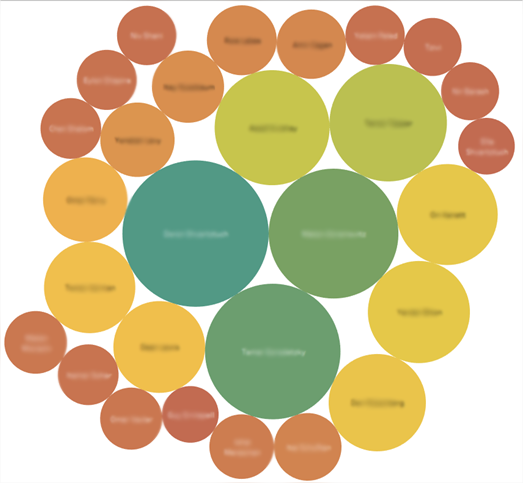

I do not easily give a “like” on Facebook, but even I know that “likes” are cheap compared with, say, the “love” reaction. I thought it would be useful to create a rating for the range of activities on Facebook, which will help me see my activity in mathematical terms and measure my affection towards a variety of Facebook friends. According to my personally devised rating scheme, a “love” reaction is worth five “likes,” and a comment is worth two “likes.” Each distinct time I spoke to someone in a chat is equal to one comment.

I ran a test using the above-mentioned rating method and used the number and “value” of interactions to compile a list of “close Facebook friends.” Being able to map my digital social life this way also allowed me to see the changes in my social sphere over time. Significant relationships clearly stood out. If I considered additional parameters including gender, age, keywords, the ratio between messages received and messages sent, tagging—Facebook has all kinds of data—it seemed very plausible that Facebook not only suggest potential romantic partners, but also approximate sexual orientation, predict the likelihood that relationships will succeed, and, why not, become a successful dating platform. Facebook recently launched a dating service, currently tested in Colombia.

Image: Yoav Tepper

Image: Yoav Tepper The next thing I did was to map all the Facebook events I had ever responded to, pin them on a timeline, and correlate the information with my Google location history. If you give credibility to the arrival status I responded to every event, it is fairly easy to pinpoint the location of the event on the map, and determine whether I was indeed present. Based on this data, Facebook can offer me events that I'm likely to be interested in.

The information stored on each of us is very different in purpose, volume, and meaning. There are many factors which influence the integrity of the data, the most dominant of which are our different patterns of behavior on the Internet, how long we are active on the social network, and which privileges we grant our apps.

While the analysis can go much further, by this point the breadth of possible extrapolations is evident. Such extrapolations may raise privacy concerns, but an understanding of what goes on in the life of users can also make our online life more conductive of social life offline.

Yoav Tepper is an analyst, musician, and developer. He works as a data expert at Nasdaq-listed surveillance and business intelligence company Verint Systems Inc. According to his Facebook data, he is also “starting his adult life,” interacting with “ads about music, technology, art, and vacation topics.” Yoav's full articles is available here .