Opinion

Guns: Just a Red Herring in 3D Printing or Something More Problematic

If a group of people was asked about the legal concerns associated with 3D printing, most would likely mention 3D printed guns. But the moral and legal debate the technology raises is much broader

For daily updates, subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

3D printing is not a young technology per se. The basic technology has been around for decades, but it has experienced a resurgence of innovation over the past couple of years. There are many different methods for 3D printing, but most involve the use of computer-aided design software (CAD) to instruct a digital fabricating machine that extrudes materials, via a layering pattern, to form objects. The technology is relatively unlimited in the materials it can print with, and in the complexity or size of the objects. 3D printers range broadly in cost and use from the industrial to home-based, and even to child-oriented devices. Notably, 3D printing is likely seeing this resurgence because of the expiration of foundational patents in the field that previously prevented too much innovation.

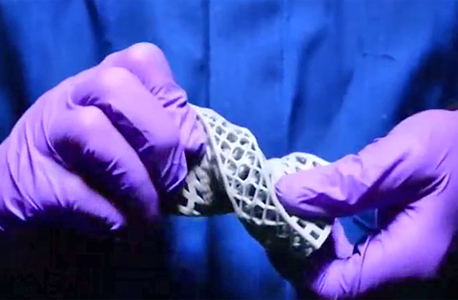

3D printing. Photo: Reuters

3D printing. Photo: Reuters

And there is a lot of current and exciting innovation. In fact, the now-dead legislation notwithstanding, gun manufacturing by 3D printing is one of the least relevant and interesting aspects of 3D printing vis-à-vis the law.

Consider the fact that in most jurisdictions in the U.S., which accounts for almost half of the worldwide multi-billion dollar 3D printing market, regular guns of the unprinted variety are relatively easy to obtain legally. There are tens of thousands of gun retailers across the U.S. that can perform the necessary perfunctory background checks prior to a gun purchase, not including the background-check-free purchases that are possible at gun shows. Many states will even let you buy the gun immediately following said background check without any waiting period (to cool off from whatever event initially drove you to buy the gun). In more than half of the states, gun owners are not required to be licensed to carry a gun, either open or concealed, obtain a permit to buy the gun, or even register their firearm.

Compare those very scary statistics with the current status of 3D printed guns: they are non-trivial to build, they work only a couple of times if at all, and they are possibly as likely to backfire and harm the user as they are to harm the intended target.

More problematic however, are the many other potential products of 3D printers. For example, soon it will be much easier to cheaply 3D print gun accessories, such as a reliable simple-minded bumpstock that can change a frightening but legal semi-automatic rifle into a terrifying and illegal fully-automatic rifle, than to buy one: last month the U.S. Department of Justice announced that bumpstocks would be regulated like machine guns as of March 2019.

Putting guns aside, what are the exciting but legally interesting aforementioned areas of innovation?

NASA recently awarded a Texas-based engineering firm a grant to create 3D food printers. According to some research, food printing technology will facilitate the incorporation of non-traditional food materials such as bug-based and high fiber plant-based materials as well as animal-based by-products. The technology can also reduce food waste by reusing materials that would otherwise be discarded after standard manufacturing processes and by only printing the food product itself with none of the associated production waste.

And just like printers can print food, they can also print medications. This use is ostensibly designed to print combinations of medications so multiple pills don’t have to be taken separately. Of course, you would usually want trained and licensed pharmacists to be the ones combining medications, not anyone who can afford a cheap printer. Similarly, people can print medical devices and/or prosthetics on their printers, making them much more affordable, albeit without the oversight that a standard device manufacturer might be subject to.

There is also the concern that individuals may print replacement parts for complex machines such as cars with potentially catastrophic results. Liabilities from such instances may not be simple to pinpoint, and may be some indeterminable combination of the source of the CAD blueprints, the printer manufacturer, the source of the raw materials for the printing, and the individual who printed the parts. This is further complicated by the fact that under U.S. law, unless you are a commercial seller of products, a random guy who prints random items in his garage is likely not strictly liable for the failure of the limited run of the product he prints and sells. Moreover, as data content is typically not considered a product under the U.S. strict liability laws, strict liability would also not attach to the underlying CAD files (intangible content and not legally a product) that were used to produce the printed product.

The law could change as 3D printing evolves and becomes much more popular, but it’s not clear how those types of increased liabilities might negatively affect innovation in this space.

Intellectual property infringement is also likely to emerge as a consequence of 3D printing. In general, IP laws are designed to create false scarcity by taking something that isn’t scarce–for example information–and placing artificial, monopoly-like restrictions on them. This scarcity works fine most of time to compensate authors, artists and inventors, but every so often a new technology comes along to threaten that false scarcity by making reproductions effortless and costless.

Just like the photocopier allowed people to easily make copies of books, and the advent of MP3s and file-sharing technology allowed people to easily violate music and movie copyrights by making the production essentially costless compared to its creation, 3D printing may allow people to trivially violate utility patents, design patents, copyrights and trademarks by making the creation of infringing products easy and cheap. 3D printing also has the added concern that counterfeiting will move out of the purview of identifiable manufacturers with determinable distribution channels, to the hard to find “everyone and anyone.”

The 2017 U.S. Supreme Court ruling in the Star Athletica case found that aesthetic aspects of useful products can be severable from the product itself and protectable under copyright law. This ruling might also allow some producers to make copyright claims over 3D printed knockoffs. It would also allow the courts to apply decades of copyright jurisprudence to these relevant suits. And like former cases of copyright infringement where content creators went after the intermediaries that facilitated infringement, it’s possible that intellectual property holders will come after those in the print-to-order business that don’t take into account whether a requested product is infringing.

However, much of the law developed over the past decades with regard to infringing copyrights, particularly over the internet, is not necessarily applicable or feasible in the area of design patents, e.g., those areas of intellectual property that have not yet experienced widespread infringement by individuals. As such the law is less developed in these areas and might initially allow unchecked infringement. The fear is that governments will attempt misguided legislation like registration of printers or watermarking all 3D-printed objects to help deal with the potential for patent infringement, given the lack of case law, potentially curbing innovation. Governments here ought to tread carefully, haven’t patents already held back 3D printing for too long?

- Now That Autonomous Vehicles Are a Reality, Are Autonomous Boats Next?

- The Battle for Net Neutrality Rages On, But Does Anyone Really Care?

- Netflix’s Bandersnatch Brings Up Ethical Questions About BMI Prosthetics

Dov Greenbaum, JD-PhD, is the director of the Zvi Meitar Institute for Legal Implications of Emerging Technologies at the Radzyner Law School, at the Interdisciplinary Center in Herzliya.

Leenore Briscoe, a student at the institute, contributed to the research and writing of this article.