From Plutarch to Beresheet: a Short History of Lunar Exploration

An outline of the history of lunar exploration, from ancient times to this day and age, in honor of Israeli spacecraft Beresheet that crashed on the moon’s surface last week

Israel’s first lunar mission came to an end last week when unmanned spacecraft Beresheet crashed on the moon’s surface. The achievement was nonetheless enormous: just sending a spacecraft 384,000 kilometers away from earth requires vast technological and scientific knowledge.

For daily updates, subscribe to our newsletter by clicking here.

Whole generations of spacecrafts got lost, crashed, or failed in some way before Beresheet, and though some may have had less knowledge and experience behind them, they did have huge governmental budgets and the extra motivational push of the space race.

The moon as captured by Israeli spacecraft Beresheet. Photo: Beresheet

The moon as captured by Israeli spacecraft Beresheet. Photo: Beresheet With a mere $100 million, SpaceIL, the nonprofit that developed and constructed Beresheet in collaboration with Israeli state-owned defense contractor Israel Aerospace Industries Ltd. (IAI), proved that you do not need the full resources of a country in order to launch a craft from earth to the moon, showing the way to future private space ventures.

In honor of Beresheet and its entrepreneurial spirit, below is a short history of lunar exploration, from ancient times to this day and age.

Greek philosopher Anaxagoras was the first to claim the sun and the moon were two flying rocks and that the light of the former reflects onto the latter. Having made this claim in ancient Greece in 428 B.C.—a highly religious and conservative period that frowned upon the shattering of widely accepted conceptions—Anaxagoras was thrown in jail and then exiled for fear of spoiling the minds of impressionable youth. Many years have passed before anyone in Greece dared to speak of the moon in a way that challenged the beliefs of the regime.

Next was Greek-Roman philosopher Plutarch, born in 46 A.D., who claimed that the spots on the moon were actually valleys and that the different shades were the result of sunlight not reaching them as strongly. Unlike Anaxagoras, Plutarch was not exiled thanks to his close ties with the rulers of the time.

Persian astronomer Habash al-Hasib al-Marwazi estimated in 825 A.D. the moon’s diameter to be 3,037 km and its distance from earth to be 363,345 km. He wasn’t far off: the moon’s true diameter is 3,476 km and its distance from earth at the perigee—the point in orbit where it is closest to earth—is 363,000 km.

Data on the moon and its orbit was also gathered by ancient cultures in China, Iraq, South America, and Central America. When Galilei Galileo first tried out his telescope in 1609, therefore, he must not have seen anything that took him by surprise. The first maps of the moon appeared by 1645, and some of the findings of that period’s astronomers are still being used. For example, “The sea of Serenity,” the area where several moon landings took place in the past and where Bereshit was also destined to land, was named by Italian astronomers Francesco Maria Grimaldi and Giovanni Battista Riccioli in 1651.

Though since disproven, the notion of possible life on the moon managed to spark the imagination of people for ages. In 1835, New York morning newspaper The Sun published a series of six articles referencing new “discoveries” it falsely attributed to British astronomer John Herschel, who was known for discovering seven of Saturn’s moons and four of Uranus’ moons, and was the Neil deGrasse Tyson of the 19th century. In its articles, The Sun claimed Herschel discovered that the moon was populated by sentient man-bat creatures, unicorns, giant rodents, and bisons. Herschel’s initial amusement at what was later known as the “Great Moon Hoax” soon turned to outrage when he was repeatedly bombarded with inquiries regarding his latest “findings.”

While the U.S. was the first to actually bring humans to our celestial neighbor in 1969 as part of Project Apollo, the first craft to land on the moon’s surface was, in fact, Soviet. On September 13, 1959, Luna 2 landed on the moon equipped with various radiation meters, a magnetometer, and two Soviet flags, so that if moon creatures did come and welcome it, they would know who sent it. Nobody came.

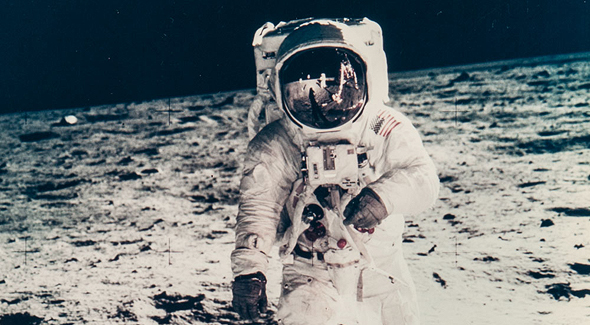

American astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the moon. Photo: NASA

American astronaut Buzz Aldrin on the moon. Photo: NASA As far as the U.S. knew at the time, the Soviet Union should have been nowhere near accomplishing a successful a moon landing. The closest the U.S. got at this point was 60,000 km away, with Pioneer 4. While the Americans were planning crafts that will approach the moon, slow down, maneuver, and land, it turned out, the Soviets built one that just crashes down on its surface but is capable of surviving the impact.

The U.S. decided to adopt the Russian method, leading to the birth of the 1960s’ Ranger program. Ranger 1 and 2 blew up during launch; Ranger 3 through 5 missed the moon or failed on the way; and ranger 6 managed to land successfully in 1964, only to stop working on the surface. The true star was Ranger 7, the first craft to send back photos of the moon’s surface in July that year.

In the meantime, the Soviet Union kept the lead. In 1966, Luna 10 became the moon’s first artificial satellite, when it entered orbit. Both space race contestants kept sending out more and more crafts, spending vast resources on the development of the technologies required for a manned launch.

A moon exploration mission can be one of five main types. The simplest one is an orbiter—a craft that enters orbit and uses cameras and long-range sensors to extract information. This is the most common kind of moon missions, with 39 orbiters launched to date.

A more complex mission is to have a craft send a probe to crash land on the moon and send back data to its mother ship. Seventeen spacecrafts set out on such a mission and most of them were successful. The problem with this type of mission is that the crashing probe does not always survive the crash, and even if it does, it is normally short-lived.

The third type of mission is even trickier—a lander craft that is capable of reaching the moon’s surface. Thirty four crafts, including the most recent Beresheet, embarked from earth so far on this type of mission. It requires a craft equipped with navigation controls, measurement technologies, and advanced flight control capabilities. For this kind of mission, the craft brings its own measuring equipment to the surface, enabling it to conduct longer, more elaborate tests with greater scientific significance.

Another type of mission is a soft landing that includes a robot, also known as a rover, which can move around on the surface, collecting and analyzing samples. Only two rover moon landings were ever successful—both conducted by the Soviet Union. China also attempted to complete such a mission in 2013 with Chang'e 3, but its robot ended up stranded and communication was lost for months before it was rebooted.

The most difficult and complex mission, so far only accomplished by the U.S., is, of course, a manned lunar landing. Six such missions were successfully completed between 1969 and 1972. During these missions, astronauts analyzed the moon’s rocks, the layer of rock dust that covers it, and various radiations, while also searching for lifeforms and useful materials.

Out of 128 lunar missions, 72 were fully successful and three were partially successful. In 35 of the missions that ended in complete failure, there were no malfunctions in the craft, its sensors, or its communications modules. In fact, in most cases, these technologies never got a chance to prove themselves as the rockets carrying the spacecraft simply exploded on the launch pad or shortly following the launch. It doesn’t matter how many backup systems a craft is equipped with or how state-of-the-art its maneuvering system is, there is no way to account for a rocket detonating while carrying dozens of tonnes of rocket fuel.

At the end of the day, if the Soviet Union had less trouble with its rockets in the 1960s, it might have been able to beat the Americans to a successful manned lunar mission as well.

Just 18 lunar missions failed due to malfunctions in the craft itself, the most famous being the Apollo 13 mission. In April 1970 the spacecraft had to abort within days and return to earth, after an oxygen tank exploded on board. The explosion was caused due to a fault in the manufacturing of its parts and the use of incompatible components.

Of the dozens of lunar missions launched since the 1960s only several were manned and fewer successful. The most obvious explanation for abandoning manned missions is the sheer cost of the operation. While up to the 1980s the Cold War continued to fuel the space race and retain U.S. interest in beating the Russians to conquering the extraterrestrial reign, as the Soviet Union began to deteriorate, giving up on manned missions altogether, the U.S. found it much harder to justify the constant expense.

- The Challenge for Beresheet 2.0: Landing on the Moon and Sticking to the Budget

- Israel to Shoot for the Moon, Again

- The Little Spaceship That Couldn’t

There are, however, further plans for lunar missions meant to explore the possibility of constructing a launchpad on the moon’s surface for future manned missions to Mars. American aerospace manufacturer Lockheed Martin is currently working to construct a reusable manned lander, expected to be completed by 2024. This time, it appears, the budget will not come solely from the government, but would also involve private entities.