Interview

Healthtech Is Israel’s Next Growth Engine, Says Venture Capitalist

Yair Schindel was a decorated army medic, a doctor, an entrepreneur, and the head of Israel’s National Digital Bureau. Now, he manages Israeli venture capital fund aMoon and wants to turn Israel into a healthtech empire

Israel is already seen as a leader in cyber, Schindel said. “If the world will also know that Israel is an exporter of health and longevity and of growing old in a healthy way, it will be a very strong brand.

Yair Schindel. Photo: Tommy Herpaz

Yair Schindel. Photo: Tommy Herpaz Schindel believes the local healthcare sector has the potential to produce at least 10 more mega-companies like Teva Pharmaceutical Industries Ltd., which currently has a market capitalization of $13.35 billion on NYSE, and Check Point Software Technologies Ltd., which trades on Nasdaq at a market capitalization of $17.04 billion.

In 2017, when Mobileye was sold to Intel for $15.3 billion, Schindel was the head of Israeli government agency the National Digital Bureau. “I saw how much added value the budget boost generated,” he said. “The implication for Israel’s economy is dramatic. It is not just the people who will work at those companies, but everything adjacent—they will grease the wheels of the gross domestic product (GDP).” Israel is focused on how to divide the budget instead of on how to enlarge the budget, Schindel said, but health tech has the potential to double the current budget, which stands at almost NIS 500 billion ($146.2 billion), and increase the GDP per capita from $40,000 to $80,000 within five years.

Schindel, 45, seems an appropriate choice to spearhead Israel’s evolution into a healthtech empire. Born to a family of physicians, he was the lead doctor of Israel’s marine commando unit the Shayetet and received a commendation for his actions in combat. After leaving the army and receiving an MBA from Harvard, he founded one medtech company and helped start another two, was involved in the founding of Maoz, a public service leadership program, and was tapped to head the National Digital Bureau.

In 2017, Check Point Software Technologies Ltd. co-founder Marius Nacht, one of Israel’s self-made billionaires, came to him with a dream to launch a giant healthtech project in the country.

“To me, everything has to do with zionism, and with healing,” Schindel said. “In our fund, alongside traditional parameters such as returns, we assess each company by how many patients it touched.”

Nacht and Schindel founded aMoon—whose website states its goal of partnering with teams who use technology and cutting-edge science to accelerate cures for the world’s most life-threatening conditions—while nursing his father, who was dying of cancer. aMoon’s first fund was created with $250 million entirely out of pocket. Today Nacht is not actively involved in the fund’s operations. It took Schindel less than a year to raise $650 million in commitments for aMoon’s second fund, and another $120 million for an early stage fund. Alongside Nacht, investors include billionaire Morris Kahn and private Israeli investors, as well as U.S. institutional investors.

Marius Nacht. Photo: Orel Cohen

Marius Nacht. Photo: Orel Cohen aMoon has invested around $500 million to date in 31 companies, 20 of them Israel-based and the rest in the U.S. “At first, the size of the fund bothered me,” Schindel said. “In the early stages, we asked ourselves if there are really enough investment targets for all this money. But when you think about it, there are similar funds in Boston, California, and New York that manage $10 billion in assets each, and those locations have less startups in the health sector than Israel—we have around 2,000 locally, and in the end we invested double what we expected.”

According to Schindel, aMoon’s activity in the U.S. came as a surprise. “Our activity there is bigger than we expected thanks to the very active network of Israelis and former Israelis, which gives us access to companies we did not think we would reach.”

In 2019, aMoon looked at 1,000 companies and ended up investing $150 million in 10 of them, but that is still twice the amount the fund expected to invest, Schindel revealed. “We will invest a similar sum in new companies this year, and I estimate that overall we will invest in 10 companies, half of them early stage.”

While Schindel is enthusiastic about the exits aMoon has already seen, he is no less excited about the developments being made by the fund’s current portfolio companies. His role in the navy combined operative activity with the development of novel medical accessories and products, he recalled. “We needed to think outside the box, and it started to stimulate entrepreneurial thinking. You need to figure out, for example, how to transfer an injured, unconscious, and intubated person from the shore to a boat or submarine; so we worked on developing heated blood and plasma products that you can administer thousands of kilometers away from land, or even on a floating gurney. You essentially need to set up an emergency room and an operating room away from any tools.”

In 2003, Schindel operated on an injured soldier in the middle of a commando activity in Nablus, an act for which he received a citation from the commander of the Israeli navy. Two years later, he left the service with a growing interest in advancing medicine via technological development. “I thought up a few ideas for startups, but understood that if that was what I wanted to do, I should study it. So instead of heading off for a medical specialization, I enrolled at Harvard.”

During his studies, Schindel met a professor from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and joined him to work at OmniGuide Inc., a company developing minimally invasive surgical tools. “Professor Yoel Fink managed the company and I was number two. We developed an optical fiber that is used to cut out certain types of malicious tumors in a much less invasive surgery than was common at the time.” In 2011, they sold control of the company to healthcare investment firm OrbiMed Advisors LLC, after working with many U.S. hospitals and treating over 300,000 patients. “It was an excellent school, and what’s more, the company is still up and running,” Schindel said.

In 2012, Schindel came back to Israel and was involved in the establishment of two other companies. The first was Medisafe Project Ltd., which developed a mobile drug compliance app and is backed by the likes of Merck KGaA (“aMoon has yet to invest in them,” he said). The second was medical analytics company Zebra Medical Vision Ltd., co-founded by CEO Eyal Gura, which went on to become one of aMoon’s star portfolio companies, with an investment by Johnson & Johnson, and an estimated valuation of $100 million.

“I gave the company its name,” Schindel said. “Doctors like to say that when you hear hoofbeats, there is a chance it might be a zebra, but odds are it is a horse. Meaning a patient might have a brain hemorrhage or a tumor, but most cases will turn out to be a migraine. Med students, of course, tend to think everything is a zebra. When I sat down with Eyal Gura, he told me ‘we will be able to recognize both horses and zebras,’ and that is how we decided on the name.”

In 2013, Schindel moved on to head Start-Up Nation Central (SNC), a Tel Aviv-based non-profit organization managing a database of Israeli tech companies and facilitating collaboration with global partners and investors. Less than a year into the job, he was approached to participate in a tender to head Israel’s National Digital Bureau, a state agency that was being launched at the time to help integrate innovative technologies into the government’s day to day operations. His public sector gig lasted less than two years, when he left due to disagreements with his superior, Minister of Social Equality Gila Gamliel.

It was not about the money, Schindel said. “When I went to work in the public sector I sold all my stock in the companies I was involved in. And anyway, I think the technology sector today focuses too much on the investors. We are the cheerleaders, at most the coaches; the stars on the court, those who determine the results, are the tech people, the entrepreneurs, and the company managers.”

Out of the nine portfolio companies under its second fund, aMoon expects three or four to go public within the next year or two, Schindel said, providing a more specific timeframe than most venture capitalists are willing to commit to. “It is sooner than we thought—the initial plan forecasted a first exit in 2022, then we moved it up to 2021, but now we understand it could already happen this year.”

aMoon identified a niche of companies that cannot live up to their potential due to financial limitations and are thus forced to find a buyer instead of growing independently, Schindel said. “For example, a company worth $1 billion or even $3 billion that is sold for $50 million or $60 million because it isn’t bringing in enough in sales, or has not achieved an FDA approval, or does not have the full clinical package. Another check of $30 million, $40 million sometimes makes all the difference,” he explained, adding that aMoon looks at companies extensively before committing. “I am not the only doctor on the team, and the investment teams spend months on every deal, look into both the science and the business side, and so when we write the check we are already pretty confident.” The fund plans to keep a stake even at portfolio companies that go public, he said.

A surprising aMoon investment that is nearing the finish line is BiondVax Pharmaceuticals Ltd. The company, founded in 2003 with the aim of developing a universal flu vaccine, listed on Tel Aviv in 2007 but disappointed investors. Its co-founder and CEO Ron Babecoff confessed to insider trading as part of an out-of-court settlement with no criminal record. Three years ago, the company delisted from TASE, though it is still traded on NASDAQ, where it listed in 2014.

aMoon invested $3 million in BiondVax for a controlling stake according to a company valuation of $15 million, and today the company has a market capitalization of $90 million—already quite a premium, but aMoon is still waiting for the big break. BiondVax is set to complete its biggest clinical trial to date, spanning some 12,000 people, by the end of 2020. “If they succeed, the company will be worth a lot more money,” Schindel said. “Existing flu vaccine technology is anachronistic, based on the strains observed the year before, and it leads to misses.”

Companies like BiondVax certainly require someone who is in it for the long haul. “It is an example of how we look at companies that have operated for years, have gone through a long arduous journey, and nothing happened,” Schindel said. “In these stages other funds are usually not interested, thinking that if nothing happened for 10 years it is probably not interesting,” he said. “That is not true, sometimes when you take a deeper look you find out it is amazing.”

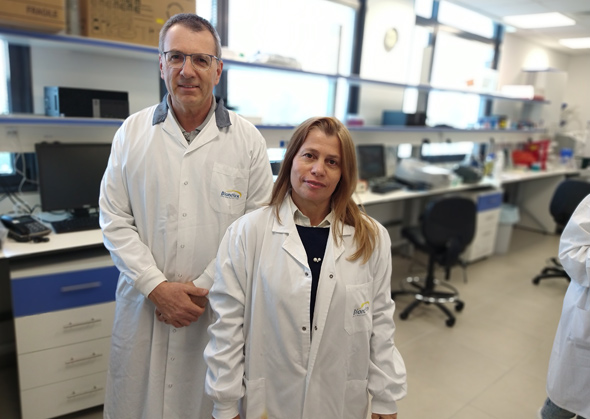

BiondVax's Ron Babecoff (left) and Tamar Ben-Yedidia. Photo: BiondVax

BiondVax's Ron Babecoff (left) and Tamar Ben-Yedidia. Photo: BiondVax One possible nearby IPO is that of Ayala Pharmaceuticals Inc., a clinical-stage company developing therapies for genetically-defined cancers. aMoon led the company’s first $17 million investment round. Another possible IPO is that of CartiHeal Inc., which develops a biocompatible, off-the-shelf coral-based implants for damaged joints. “CartiHeal had a significant development recently,” Schindel said: the company recently published results of an interim analysis of a study, and showed they have a 95% probability of success based on the interim results.

Another ripe company, according to Schindel, is Theranica Ltd., which develops electrical nerve stimulation (ENS) technology for controlling migraines. In 2019, the company’s technology was chosen by the Times for its best inventions for 2019 list. “Now sales have started,” Schindel said. In Theranica’s case, aMoon’s timing was especially successful: in March 2019 it participated in a $35 million investment round in the company, two months ahead of the company’s FDA approval. MDClone Ltd., which develops a system for ensuring patient confidentiality during the analysis of medical data, is also an IPO contender. “It is the ultimate big data—all the medical data is real, but the personal details of the patients are fictional so there are no privacy concerns. This enables the creation of giant databases that can be shared between hospitals.”

While Israel is quickly becoming a medtech and healthtech hub, these innovations rarely impact everyday life in the country. “The regulation and openness in Israel need to change,” Schindel said. “We need to be quicker to approve drugs and devices, processes here are outdated and slow, and there is not enough manpower and resources. There are many products that have been approved in the U.S. and Europe but the Israeli regulator does not sign off on them.” aMoon, he said, is part of the 8400 health network initiative, a coalition of 400 leading executives attempting to solve this problem.

Schindel is also working to advance the opening of a local FDA branch in Israel. U.S. Secretary of the Treasury Steven Mnuchin already visited the country in October to discuss the matter, and an FDA delegation is also slated to visit soon. “A local FDA branch will ease the situation for local companies and save on costs,” he said. “Another option currently being considered is that the government change the regulation to enable clinical processes here ahead of the final FDA approval stages.”

- An App a Day Keeps the Doctor Away: 8 At-Home Health Monitoring Startups

- God Willing, He Will Cure Cancer, and Shrimp

- Teva’s Small Print Gives Rise to Optimism

Interest in the healthtech sector is not just the purview of hedge funds and medical companies anymore, either. Like Nacht, many of the local tech millionaires—from cyber, fintech, and AI—are turning to the sector. “It is a combination of great economic potential and a desire to help the world,” Schindel said. “They continue to believe in capitalism and technological superiority, but the fact that they can leverage their power for accelerated healing is a game changer. Some think of their parents, their children, themselves. If I can identify and solve problems like Alzheimer's or diabetes early, then it pertains to everyone.”

In venture capital, of course, there are successes and there are losing bets. “There are three companies we erased,” Schindel said. “There are also probably a lot of companies we said no to that should have been a big yes. All funds have the anti-portfolio. Bessemer Venture Partners initially asked those ‘two clowns from Google’ what anyone needs another search engine for.” Bets that fail are frustrating, but part of a business, he said.