Exclusive

Israeli Cyber Startup Senpai Helped Malaysia’s Corrupt Leader Spy on Opposition

Documents submitted to an Israeli court revealed Senpai’s methods of operation and its ties to questionable regimes, including its $1.5 million deal to supply Malaysia’s intelligence agency with surveillance tools to be used on civilians

During the campaign, no less than 2,300 candidates were attempting to dethrone Najib, who, throughout his 10-year reign, had rolled back human rights in the country, persecuted minority religious groups and members of the LGBTQ community, diminished free speech, and limited the freedom of the press. Najib was also accused of embezzling billions in state funds, and he and his family members were known for their lavish, eye-popping lifestyle.

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak. Photo: Bloomberg

Malaysian Prime Minister Najib Razak. Photo: Bloomberg The pressure felt by Najib’s party, the United Malays National Organisation (UMNO), was so immense that, just over a month before the election, the Malaysian government signed a deal to acquire a system that allowed it to gather information and analyze data on civilian activity. The system was meant to be used by Malaysian intelligence agency the Special Branch (SB) to surveil political activists for the opposition, according to court documents obtained and reviewed by Calcalist. The company that developed and supplied the system to the Malaysian government was Senpai Technologies Ltd., a small Israeli cybersecurity startup.

Read More:

Amnesty International Takes Legal Action Against Israeli Surveillance Company NSO

The Iranian Cyber Threat can no Longer be Underestimated

Spy Agency’s Phone Surveillance Detected a Third of Israel's Covid-19 Cases

The deal was signed in April 2018 with a price tag of $1.5 million and received the code name “Project Magnum.” Since Israel and Malaysia have no official diplomatic relations, the deal was signed through a Cypriot conduit company called Kohai Corp. Ltd., founded by two Senpai shareholders for the sole purpose of serving as a front for such deals. The Malaysian government’s plans for Senpai’s system were not kept secret from the company and its use for “political investigations״ is specifically mentioned in internal email correspondence.

Malaysia was not Senpai’s only controversial potential client and, according to documents reviewed by Calcalist, it had previously negotiated a deal to sell its services to the Sultanate of Oman on the southeastern coast of the Arabian Peninsula, which also has no diplomatic ties to Israel.

Not many have heard of Senpai, whose activity has since been frozen, but it is just one in a long line of Israeli cyber companies that do not shy away from working with totalitarian regimes and countries that have no relations with Israel. Like many of its competitors, Senpai aimed sky high. In May 2019, it was reported that Senpai is planning to join cyber-focused consortium Intellexa Ltd., in hopes of forming a market-leading alliance that could compete with companies, such as NSO Group and Nasdaq-listed Verint Systems Inc.

A surveillance control room. Photo: Nitzan Sadan

A surveillance control room. Photo: Nitzan Sadan Senpai’s flag product was RogueEye, a system that collects information on people from openly available online sources, such as social networks, and cross-references and analyzes it to produce intelligence reports for secret services, police forces, militaries, and business entities. Among RogueEye’s official data collection methods is a network of avatars (fake social network profiles) that follow the target and extract information through direct interaction with them.

A year after the election in Malaysia, according to correspondence obtained by Calcalist, Senpai was getting ready to sign a new contract with the SB that required adjusting the goals of the original contract in light of UMNO’s staggering defeat. “The client got the documents and we are waiting for his response,” Senpai co-founder and head of sales Roy Shloman said referring to “Magnum” in an email sent to fellow co-founders Guy David, Omri Raiter, and Eric Banoun on June 10, 2019.

A document submitted to court

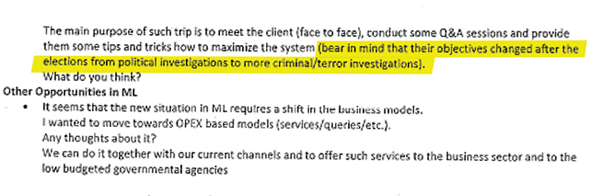

A document submitted to court “As you know, after the elections many things changed and became a bit more complicated,” Shloman wrote. “As for the client’s management process and based on some of the past conference calls with them, I think that we shall plan a visit to KL (Malaysia's capital Kuala Lumpur, TG and HR)” he added.

"The main purpose of such a trip is to meet the client (face to face), conduct some Q&A sessions, and provide them with some tips and tricks on how to maximize the system,” Shloman continued. “Bear in mind, that their objectives changed after elections from political investigations to more criminal-terror investigations,” he wrote.

In his email, Shloman said he believes the changes in ML (Malaysia, TG and HR), should bring Senpai to change its business model. “We can do it together with our current channels,” he wrote, “and to offer such services to the business sector and to the low budgeted governmental agencies.”

Eric Banoun. Photo: PR

Eric Banoun. Photo: PR For Malaysia’s phase two agreements, Banoun counted, $300,000-$400,000 from the SB, between $2 million and $2.5 million from the country’s Prime Minister’s Office, between $800,000 and $2.2 million from the Malaysian Anti-Corruption Commission, and a similar sum from the police. Banoun also mentioned a potential deal in Oman for between $1.2 million and $2.5 million. It is unclear whether these deals were eventually signed.

Najib first rose to power in 2009 when he won the Prime Minister’s seat in a landslide. This came as no surprise, as Najib’s father before him was a beloved prime minister who also headed UMNO, the country’s ruling party since it declared independence in 1957. Najib’s father, Abdul Razak Hussein, had a record of top government roles including as the minister of defense, the minister of education, and the minister of finance and was considered the one responsible for saving Malaysia from the 2008 global financial crisis.

Abdul Razak was popular thanks to his liberal policies that placed great importance on direct communication between the government and its citizens and on financial growth, which was essential to the prosperity of the developing country.

After his election, Najib established a government investment fund called 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), intended to invest in global collaborations. The Malaysian government transferred over $1 billion to the fund, which raised an additional sum of at least $6.5 billion in state bonds. Following various media reports and a rigorous investigation by the U.S. Department of Justice, it appeared the fund benefitted Najib and his associates most of all.

In its first months of activity, 1MDB invested billions of taxpayer Malaysian ringgits in a line of shady companies, some of which seem to have been established for this sole purpose. The fund’s management was entrusted in the hands of Jho Low, a little-known businessman, who was friends with Najib’s stepson as well as with several billionaires from the Gulf States.

It is possible that the alleged grandiose embezzlement would not have come to light if the people benefiting from it led a slightly more modest life, but they did the complete opposite of that. Low became famous for organizing grandiose parties. He paid American superstars, including Paris Hilton and Jamie Foxx, millions just to hang out with him, hired Britney Spears to jump out of a cake, and gifted luxury Bugatti cars to friends.

Najib’s second wife, Rosmah Mansor, rightfully earned the nickname the Malaysian Imelda Marcos—after the former first lady of the Philippines, known for her lavish lifestyle—due to her fondness for spending. According to the U.S. Department of Justice’s findings, Rosmah spent at least $6 million taken from the state fund. At one time, Rosmah reportedly filled a jet plane with luxury items acquired on a single shopping spree.

Malaysian taxpayer money funded the prime minister and his entourage’s frighteningly lavish lifestyles. Among Najib’s assets are three Manhattan properties: a $30 million penthouse at the Time Warner Center, a $33 million condo at Park Laurel Condominiums, and another $51 million penthouse. He also owns a $31 million mansion in Beverly Hills, a Los Angeles home priced at nearly $40 million, a $42 million London townhouse, a private business jet by Canadian company Bombardier Inc., nearly $100 million worth of paintings by Vincent Van Gogh and Claude Monet, and a Hollywood production company that was behind the 2013 hit starring Leonardo DiCaprio, “The Wolf of Wall Street”, which ironically dealt with the hedonistic lifestyle of another embezzler.

Protests in Kuala Lampur. Photo: Getty Images

Protests in Kuala Lampur. Photo: Getty Images Tim Leissner, then a partner at Goldman Sachs responsible for south-east Asia, also wanted a piece of Malaysia’s billion-dollar pie. Subsequently, Goldman Sachs issued $3.5 billion worth of bonds for 1MDB in exchange for $600 million, some 200 times the normally accepted fee. According to the allegations, this excessive payment constituted a bribe for turning a blind eye to the fund's corruption and illegal activity.

By 2015, 1MDB was in so much debt, that the Malaysian government had to find additional sources to fund it. Among other things, it emptied the national Hajj fund, used by the country’s Muslim majority to save for a pilgrimage to Mecca. Many citizens deposited money there for decades to be able to afford the religious ritual, which every observant Muslim is required to perform at least once in their lifetime.

When the embezzlement became public around a year later it led to a vast public outcry in Malaysia. Najib responded to the protests with a strong hand, jailing oppositionists and promoting legislation limiting the right of protest. The closer the 2018 election got, the more tense the situation in Malaysia became.

In January that year, Najib’s political mentor, Mahathir Mohamad who was the country’s prime minister between 1981 and 2003, announced he will be running for the seat again to fight corruption. Najib then decided to take his efforts to crush the opposition up a notch, and that is when Senpai came in the picture.

It is not often that government spy deals are exposed, and it is even more rare to find written evidence that the supplying company was completely aware of the type of use a government intended to make of its product. In fact, if it were not for a financial dispute between Senpai’s co-founders, which found its way to a Tel Aviv court last year, the documents and correspondence exposing the company’s extensive activity would likely not have seen the light of day.

According to the documents submitted to the court, Senpai also provided its services in Mexico, Aquador, Gabon, Angola, Kenya, Indonesia, and Singapore. The price list it presented to potential clients ranged between $1.2 million and $1.6 million for the RogueEye system, $750,000-$1 million for the operation of avatars, and between $30,000 and $70,000 in monthly fees. Overall, Senpai’s deals since its establishment in 2016 amounted to over $9 million.

Officially, Senpai claimed its system only collects publicly available data, but correspondence between Shloman and one of the company’s salesmen, submitted to the court and reviewed by Calcalist, revealed that RogueEye also analyzes data from phones infected by spyware. The salesman, one Gregory Krasnostein, specifically wrote to Shloman that “Senpai’s system collected the data from the infected phone and is analyzing it.”

But, even Senpai’s officially declared activity of mining data using fake accounts is not free from ethical and legal concerns. “Using avatars to gather information is a very common practice for cyber companies,” an executive from the Israeli cyber industry told Calcalist on condition of anonymity. “This lets you collect information without having to hack anything and on some websites, for example, online forums, nobody uses their real name anyway,” he added.

It being common practice, however, does not necessarily also make it legal. “This is a complex issue in international law,” the executive said. “Consider, for example, creating a fake user to converse with a hacker and exchange information that I need to defend a client. Is it morally acceptable to negotiate with a criminal, even to exchange information with them? It would appear that the right course of action is to report them to the authorities.”

Senpai, like other Israeli cyber companies, chose to sell its services and products to countries that have no diplomatic relations with Israel through conduit companies. “This is a very common practice for Israeli companies that station most of their workforce outside of Israel,” the executive said.

It is important to keep in mind however, he said, that offensive cyber companies must gain an export license from the Israeli Ministry of Defense. He mentioned one well known company that has the ministry’s approval yet sells to Gulf States through its subsidiaries. This means that Israel is either fully aware of its conduct, or that the company is covering its tracks and fooling it using various business entities, he said. “Gulf States on their part also need to cover their tracks when buying Israeli technology,” he added.

Another executive at a large cyber company who spoke to Calcalist on condition of anonymity said that more often than not, the client countries are even more reluctant to be associated with an Israeli product. “The offensive cyber industry,” he said, “is, in a way, parallel to the conventional military industry. Spyware may not kill people, but it does give the state a lot of power against its citizens.”

As previously mentioned, Senpai is just one of many Israeli cyber companies linked to non-democratic regimes, shady clients, controversial practices, or run-ins with the law. NSO, the developer of spyware Pegasus is perhaps the best known of the bunch. In October, encrypted messaging app WhatsApp and its parent company Facebook filed a lawsuit against NSO alleging the former and its Luxembourg-based affiliate Q Cyber Technologies Ltd. used WhatsApp’s servers to deliver malware to approximately 1,400 devices, to surveil certain users, around 100 of which were human rights activists and journalists.

NSO co-founders Omri Lavie (right) and Shalev Hulio. Photo: Bar Cohen

NSO co-founders Omri Lavie (right) and Shalev Hulio. Photo: Bar Cohen Other Israeli companies to be linked to questionable regimes and surveillance against civilians are Cyberbit Ltd.—recently sold to American Investment firm Charlesbank Technology Opportunities Fund by its parent company Israeli defense contractor Elbit Systems Ltd.—which, according to Canadian research center The Citizen Lab, provided the Ethiopian government with spyware software that was used to track journalists and dissidents; AnyVision Interactive Technologies Ltd., whose facial recognition technologies were reportedly used by Israeli forces to spy on Palestinians in the West Bank, costing it an investment from Microsoft; and DarkMatter, which operates out of the United Arab Emirates and employs veterans of Israel’s military intelligence and technology units. According to the New York Times, DarkMatter developed a popular chat app called ToTok, which turned out to be a means for the Emirati government to spy on its citizens and extract data from their phones.

The severity of the cases in which Israeli companies were involved, brought David Kaye, the United Nations’ special rapporteur on the promotion and protection of the right to freedom of opinion and expression, to name Israel in a May 2019 report calling states to “impose an immediate moratorium on the export, sale, transfer, use or servicing of privately developed surveillance tools until a human rights-compliant safeguards regime is in place.”

Kaye explained his position, writing that “surveillance of specific individuals—often journalists, activists, opposition figures, critics, and others exercising their right to freedom of expression—has been shown to lead to arbitrary detention, sometimes to torture, and possibly to extrajudicial killings.”

Kaye also mentioned NSO and Israel’s refusal to revoke its export license. He also wrote that a lack of substantial international pressure and a veil of secrecy justified by claims of national security are a major obstacle in regulating the export of cyber offensive technologies.

Kaye also mentioned that despite being one of the world’s biggest offensive cyber exporters, Israel is not an active member of the Wassenaar Arrangement, an international arrangement meant to regulate the sector. Israel has included items from the Wassenaar Arrangement’s control list to its own list of controlled goods, Kaye wrote, yet its level of enforcement in the country is unclear.

Senpai was founded in 2016 by five local tech veterans: Shloman, Banoun, David, Raiter, and Jonathan Lampert. Banoun was formerly employed by the cyber and intelligence unit of Nasdaq-listed software company Nice Ltd. and helped NSO market its Pegasus system to a country that cannot be specified due to a court-mandated gag-order. Lampert served as a sales manager for several defense contractors, including Paz Logistics Ltd., which, according to the U.S. Department of Justice, served as a mediator for the sale of military products to foreign law enforcement agencies. Shloman, according to his LinkedIn page, was formerly an executive at Verint.

Last month, the dispute between Senpai’s co-founders ended when the parties signed a confidential settlement and requested the court cancel the lawsuit. The lawsuit was originally filed by Lampert, Banoun, and Shloman, who alleged that their partners David and Raiter conspired with Dillian to steal the company away from them. Though it remains unclear if Senpai was indeed sold to Intellexa in the end, its system is currently offered to clients on the latter’s website.

The lawsuit also alleged Dillian was subject to an investigation by the internal military police for fiscal irregularities which led to his dismissal from the army. In 2019, Dillian was involved in a high profile affair involving a “spy van” confiscated by the Cipryote police. The van was developed by a company co-founded by Dillian in which Banoun was also a party.

Senpai’s activity was not enough to save Najib and UMNO’s regime, and shortly after losing the 2018 election, he was arrested by the Malaysian authorities on suspicion of receiving some $10 million as a bribe from a private company. The Malaysian police froze Najib’s assets, confiscating more than $220 million worth of real estate properties, diamonds, jewelry, purses, and watches. Najib’s trial began in April last year and is still ongoing.

Human rights were at the heart of the 2018 Malaysian election and their repeated violation was among the main reasons that brought Najib down. In his campaign, Najib’s opponent, Mahathir, focused on promises to annihilate corruption and cleanse Malaysia from Najib’s anti-democratic practices. Old habits, however, die hard, and despite his many promises, as prime minister, Mahathir has only enacted a fraction of the reforms he had promised in his campaign. Even though many of Najib’s draconian laws were canceled by the new government, quite a few laws were left in place, giving the regime extensive power over the press.