Tech and Academia leaders urge AG to charge Netanyahu with sedition

Accusers claim the prime minister’s speech outside his courtroom was a tangible call to harm judges and Israel’s rule of law

The impetus for the requests, which was penned by attorney Daphna Holtz-Lechner was the prime minister’s speech on the 24th of May, moments before the start of his trial, which according to the letters’ authors perfectly matches the definition of sedition according to article 133 in thepenal law. Netanyhau was indicted on charges of bribery, fraud and absruction of justice following years of investigations into alleged corruption offenses.

Benjamin Netanyhau delivers a speech ahead of his trial on May 24th. Photo: Yonatan Zindel/Flash90

Benjamin Netanyhau delivers a speech ahead of his trial on May 24th. Photo: Yonatan Zindel/Flash90 The impressive professional and personal record of the petitioners and the professional reputation of their attorney make it difficult to categorize the appeal as absurd or bizarre. And yet, the question arises whether this is a public relations stunt or a legally feasible effort. “These are dark times,” says Holtz-Lechner, “during which the prime minister is using his voice and every other governing tool at his disposal to lash out and rally the public against the judicial system. In his acts, he has allegedly struck a severe blow to Israeli democracy.” She draws a direct line between the speech and subsequent actions that entailed threats directed at judges Anat Baron and Uzi Vogleman, calls to arrest Channel 10 journalist Raviv Druker, and a physical attack on television analyst Amnon Abramovich, from which he was saved at the last minute.

The chances that Mandelblit actually orders the opening of an investigation on the suspicions are slim. Other, seemingly more logical petitions, such as the request to prevent the indicted prime minister from assembling the governments, or the call to investigate Netanyahu’s involvement in the submarine affair, were rejected. If so, why not put the sedition option on the table too? Especially seeing how Netanyahu’s words at the start of his trial fit the letter of the law like a glove: “the arousal of hatred, contempt or disloyalty toward the State or its lawfully constituted administrative or judicial authorities.” The speech was indeed packed with hatred and contempt for the state authorities: “Elements in the police and State Attorney’s Office banded together with left-wing journalists… to fabricate baseless cases against me,” said Netanyahu. “These investigations were corrupted and fabricated from the start. This is an attempted political coup against the will of the people.”

The prime minister also named names in his speech: former police chief Rony Elsheich, former senior prosecutor Shay Nitzan, and investigative reporter Ravid Druker among them. If the words of the sedition clause were to be drafted today, Netanyahu’s speech could have been the model and inspiration for lawmakers.

Netanyahu and his supporters naturally claim the right of freedom of expression and freedom to criticize and point out failures. If we put aside for a moment the lack of respect and tolerance to critics of the sovereign, there is indeed a deep-grained problem in the definition of the crime: where is the line between legitimate discourse and criminal incitement and sedition? The test is often one of probability, asking what are the chances that the words will actually lead to acts of incitement or sedition.

Until prime minister Yitzhak Rabin was murdered, there was a debate over whether freedom of expression protected incitement to violence against him by rabbis, politicians, and protesters. The debate continued after the murder surrounding the questions of whether there was a causal connection between the words and the murder. Evaluating potential risk is always speculative while silencing speech is immediate and tangible. The High Court has long expanded, nearly to infinity, the protection of free speech. Now, ironically, the court and its judges are under threat because of that leniency, and by none other than the prime ministers and his supporters in the political system, in the streets, and particularly on social media.

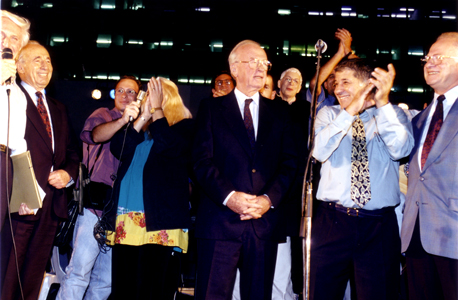

Slain prime minister Yitzhak Rabin moments before being shot at a peace rally in 1996. Photo: Michael Kramer

Slain prime minister Yitzhak Rabin moments before being shot at a peace rally in 1996. Photo: Michael Kramer The probability of danger does not rely solely on the statements’ content, read one of the rulings, “sometimes the public atmosphere in which the statements were made, the locations they were uttered in, their timing or their audience, also bear weight. These can all instruct on the probability that the statements constitute sedition.” Holtz-Lechner details the circumstances in which the speech was given that she believes strengthen the case for potential sedition: the speaker’s status and position of power, his immense influence over his supporters, the time and place the speech was given, minutes before entering the courtroom, and the use of symbols and tools of power and authority. Netanyahu didn’t just drag his official podium to the courthouse, but also his most senior ministers, who surrounded him like a human backdrop, she argues. “In this way, Netanyahu committed the crime of sedition,” she wrote in the letter to Mandelblit, “the unprecedented harm these actions did to the law enforcement authorities and the justice system of the State of Israel, qualify as near-certain probability from a legal perspective.”

Incitement to murder and sedition express two sorts of threats: to people and to the structure of governance. In the past, the attorney general had refused to indict prominent rabbi, Ovadia Yosef, for saying: “Damn Yossi Sarid he should be rooted out of this world.” Later the AG and the High Court refused to prosecute the authors of a book titled “The King’s Torah,” which detailed when it is permissible for Jews to kill Arabs. In another case, the High Court judges were split on whether sedition was meant to protect only the stability of the regime or also its democratic values. It seems as if Netanyahu and his helpers, at home, in the party, and in the street protests, are offering a package threat deal: against judges, prosecutors, journalists, and the state’s lawfully constituted administrative or judicial authorities (particularly its judicial authorities) and also on its democratic values.

An appendix attached to the letter includes the professional assessment of a social media expert, who provides evidence from posts that support Netanyahu of the levels of hatred and vitriol aimed at his critics. In starring roles are the Supreme Court Judges, Mandelblit, prosecutors and journalists. She highlighted a video predicting that the attorney general’s fate is to be hanged from a high tree and another that showed supreme court judge Hanan Meltzer’s face intermittently transposed with that of a skull. These, the authors of the letter believe, meet the definition of sedition. “Tangible results of the hatred and contempt and disloyalty that Netanyahu’s seditious acts against the judicial authorities led to can be found in these horrible and dangerous threats aimed directly and in an unrestrained fashion towards Supreme Court judges, and pose a real threat to their lives, threats that resulted in the placement of bodyguards to protect the judges,” read the letter to Mandelblit, who himself is under state protection.