Warning: the following game is, in fact, a drug

The FDA recently approved a video game as a prescribed drug for the treatment of ADHD in kids, opening the door to the development of new chemical and side-effect free treatments that can also be fun

Then, one night, after months of dead ends, Gazzaley dreamt of a racing video game with alien characters and psychedelic colors.

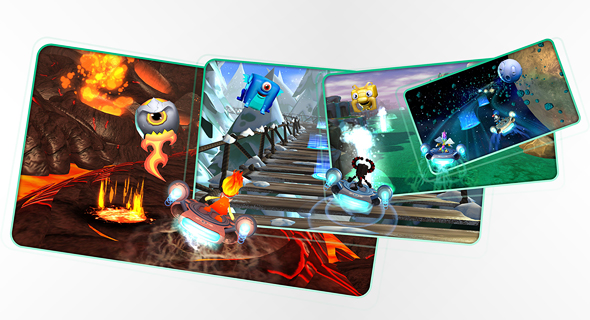

EndeavorRX was approved as a drug by the FDA. Photo: PR

EndeavorRX was approved as a drug by the FDA. Photo: PR In a recent video call interview with Calcalist, Gazzaley said he started making sketches as soon as he woke up. Twelve years later, these sketches matured into an unprecedented achievement that will soon be hitting the market: EndeavorRX, a video game aimed at children aged 8-12 with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). It is also the first video game to ever be approved as a drug by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

According to the company that developed the game, Akili Interactive Labs Inc., in clinical tests, a third of the children examined showed significant improvement in their ability to concentrate after playing the simple game for one month.

The objectives of the game may sound trivial—collect artifacts and avoid obstacles—but they are exactly the type of tasks that people with ADHD need to work on. Most importantly, as could be expected from a virtual drug, the game has little to no side effects compared with conventional drugs.

For the FDA, approving a game as a drug is not just a precedent but a declaration of intent. EndeavorRx “offers a non-drug option for improving symptoms associated with ADHD in children and is an important example of the growing field of digital therapy and digital therapeutics,” Jeffrey Shuren, director of the FDA’s Center for Devices and Radiological Health, said in a statement released last month . “The FDA is committed to providing regulatory pathways that enable patients timely access to safe and effective innovative digital therapeutics,” Shuren added.

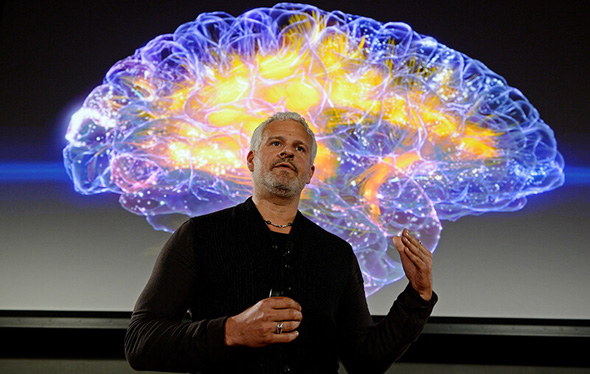

Gazzaley, 51, was a gamer from an early age and views himself as a member of the Atari generation, and, as a kid, he used to hack games to raise his score. Until a very advanced stage in his career, however, Gazzaley, who studied biochemistry never thought of himself as a video game developer. He started out studying biochemistry at the State University of New York at Binghamton before moving on to the prestigious Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York.

Adam Gazzaley. Photo: AFP

Adam Gazzaley. Photo: AFP Gazzaley said he never stopped gaming, except during his internship when he did not have the time, and was always on the lookout for projects that connect between neuroscience, media, and entertainment.

Among the projects that have brought Gazzaley fame, was a collaboration with Grateful Dead drummer Mickey Hart. The two developed a system that played video art based on Hart’s brain waves during a live performance.

Still, Gazzaley’s love for gaming remained not much more than a hobby. But then, in 2008, he saw the light. Gazzaley said he was really frustrated by medicine’s dependence on pills and molecules and wanted to find a new approach to “fixing the brain.”

Assorted pills. Photo: Pixabox

Assorted pills. Photo: Pixabox

In the 12 years since, Akili developed various therapeutic games, including NeuroRacer, designed for adults suffering from dementia, but the holy grail was always an FDA approval.

Trying to treat ADHD through video games may sound like a simple attempt to win the hearts of kids, somewhat like the educational software that was installed on every school computer in the early 1990s, but EndeavorRX is much more than that. People have known for thousands of years that various experiences affect the brain, Gazzaley said, giving mindfulness techniques, education, and psychotherapy as examples. What he set out to do was to create an experience that would make users adaptively react to challenges in their environment.

Akili International's Endeavor RX. Photo: screenshot

Akili International's Endeavor RX. Photo: screenshot Gazzaley quickly realized however that even if he could develop a tool that works, the main challenge would be to get people to use it for 30-60 minutes a day. He then thought of ways to get people to spend 30 minutes a day in front of a screen and then it hit him: some people do it willingly for 10 hours a day, they are called gamers. All that was left to do was to take the tool developed in the lab and build a game around it, preferably a fun game.

According to Gazzaley, in order for it to work, there was no need to create an interactive experience as the brain can also be affected by simply seeing something. Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), for example, he said, is caused by seeing something disturbing.

But Gazzaley wanted to create an interactive experience so that the challenge and the reward could adapt to the patient’s progress. If, in a regular game, the player chooses the difficulty level, Gazzaley said, he wanted to create a game that becomes more difficult as the player gets better, just enough to challenge them and keep them engaged. “The vision is that the computer processor and the processor between your ears would become one.”

One side effect Gazzaley noted in his official research was a sense of frustration. The game always pushed you, he said, you cannot fall off the lane, otherwise, you would quit, but, like any good trainer, it always wants you to put in an effort. Some kids, he explained, do not enjoy these types of challenges and become frustrated and these are normally the same kids that do not enjoy regular video games either. Other kids, he said, feel the game isn’t hard enough.

A child playing a video game. Photo: shutterstock

A child playing a video game. Photo: shutterstock It sounds almost absurd to think of fun when you are talking about an experimental treatment, but this is the new reality and we better get used to it. Gaming is constantly changing and Gazzaley’s luck was to reach the FDA with his game, just as the perception of what can be done in the field is expanding.

Still, it was a long journey that included seven years of clinical trials participated by over 600 children. Officially, the FDA says it welcomed digital technologies, Gazzaley said, but, in reality, you need to convince an array of scientists, researchers, clerks, and critics, all with their own preconceptions on the prospect.

What worked best, Gazzaley said, was not to philosophize on what games can or cannot do, but just let the results of the trials speak for themselves.

- Online gaming company Playtika targeting $10 billion IPO

- Is Mobile the Future of Gaming? Twitter’s Head of Gaming Certainly Thinks so

- How Covid-19 Might Create an Onerous Economy Inside Video Games

Gazzaley and his team created trials similar to those undergone by traditional drugs, complete with a placebo game that was used on a control group. Focusing on the results of the clinical trials, helped convince the skeptics.

An FDA approval has been coveted by gaming companies for nearly a decade. In 2011, San Francisco-based company Brain Plasticity Inc. tried and failed to gain approval for a game meant to improve the memory and attention span of patients with schizophrenia. In 2015, Akili first attempted to gain the approval with an earlier version of EndeavorRX, while another competitor, Posit Science Corp., made a similar attempt.

All of these attempts failed to get the FDA’s seal of approval as there was no proof that the effects of the game lasted when the user was no longer playing.

It is difficult to say whether, in the five years that have since passed, Akili managed to tweak the game or its trial system or whether the FDA’s approach towards new technologies just changed. It appears to be a little of both.

The FDA’s relatively open approach towards gaming is not to be taken for granted and may have been influenced by a broader change in the way we think about video games, brought about by the events of recent months.

A child playing a video game. Photo:Shutterstock

A child playing a video game. Photo:Shutterstock Asi Burak, chairman of Games for Change, a community for socially engaged games, believes the global lockdown brought about by the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic deserves some of the credit for improving the public image of video games.

"This needs to be said very carefully as we are in a terrible situation, with countless people who have either died, gotten sick, or became unemployed, but gaming is skyrocketing,” Burak, said in an interview with Calcalist from his home in lockdown New York, one of the most serious outbreak sites in the world.

All of a sudden, Burak said, everyone started to see the benefits of gaming both for social and commercial causes that we were talking about. “It was always so difficult to get people to see that but suddenly it became almost intuitive,” he said.

“I have two daughters that go to a very advanced and technological school in New York and even there I hear parents completely opposed to screen time and games,” Burak said. “It is absurd,” he explained, “that you have such a strong medium with such a massive potential impact and you think the only thing that can be done with it is silly and superficial entertainment.”

According to Burak, a lot has changed over the past two decades. “I remember how, in 2004, we were trying to promote social games and we had to use vocabulary from a previous media, film, and we would call what we do an interactive documentary,” he recalled.

A girl playing a video game. Photo: Shutterstock

A girl playing a video game. Photo: Shutterstock “Now, left with no other choice, everyone opened their eyes to the positive aspects of games, such as distance learning and a way for kids to hang out together while they’re stuck in their respective homes,” Burak said, adding even the World Health Organization (WHO) recently recommended video games as an acceptable leisure time activity during the pandemic.

What Burak is referring to is a March announcement by WHO of a campaign it was launching together with gaming giants including Call of Duty developer Activision Blizzard Inc. The campaign encouraged homebound kids and adults to take up gaming as a hobby under the hashtag PlayApartTogether.

This was nothing short of an earthquake, representing a 180 degrees shift in WHO’s previous stance on video games. The announcement came just one year after adding gaming addiction to its list of mental disorders.

While the existence of gaming addiction is hard to deny and a medical classification is just a way to get those suffering from it the help they need, WHO’s actions did strike a nerve with the industry. Critics claimed the organization only strengthened stereotypes associated with a hobby that already has a non-justifiably bad reputation. From this perspective, WHO’s newly found stance indicates a shift in the perception of this young medium.

"For years,” Burak said, “people had this perception of gamers as a separate human species. This may have been true when you only had computers and consoles, but in the mobile phone age, we are no longer talking about hundreds of thousands of gamers but of 2 billion players.”

Earlier this week, market intelligence company Newzoo International BV estimated there will be around 3 billion gamers in the world by 2023, 39% of the global population.

Participants in a gaming competition in Germany. Photo: Blooberg

Participants in a gaming competition in Germany. Photo: Blooberg “There is no fighting it,” Burak said. “Parents can weep over screen time all they want, but right now it is what is saving their kids from infection outside and loneliness,” he added.

While working to promote the adoption of EndeavorRX among the U.S. medical community, Gazzaley is already thinking about his next project. The basic concept of a rewarding interactive experience can be applied to any field, including, for example, cognitive behavioral therapy, he said.

Gazzaley is currently examining games that use the principles of meditation and are played with eyes closed. Players focus on their breathing, touch the tablet, and get feedback and points, he explained, adding it helps adults concentrate and reduce stress levels.

Perhaps this is exactly what the Buddhists were missing all along: reaching enlightenment is nice and all, but winning points and ranks on the way is much better.