Analysis

Israel’s education system fails the Covid-19 test

With just two weeks before the new school year, the Israeli Ministry of Education prides itself in its back to school outline, yet the plan is full of holes and will likely only widen the gap between stronger and weaker students

While it is undoubtedly better than distance learning throughout the week, it might nonetheless be nothing to brag about. Delving into the fine details of the outline reveals many holes and severe ramifications the ministry did not adequately account for.

Education minister Yoav Galant. Photo:Omer Mesinger

Education minister Yoav Galant. Photo:Omer Mesinger “These kids will end up on the street,” Dan wrote, “and from there the path to drugs and crime is very short. In other words, the plan would manufacture 140,000 potential criminals in Israel and we will see its consequences in a few years, as the country will face a wave of criminal activity, the magnitude of which it has never experienced before.”

Dan referred to what she calls “transparent dropouts,” meaning those students that remain enrolled in the system but only partially attend. Her assumption is that for every official dropout there are two transparent dropouts, for whom the only drawing points to the system are social ties.

Not having a steady place to go every day might sever these ties, Dan worries. And she is not the only one. The United Nations’ Secretary-General Antonio Guterres recently warned of a "generational catastrophe that could waste untold human potential, undermine decades of progress, and exacerbate entrenched inequalities," due to the closure of physical schools in light of the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic. Guterres named child nutrition, child marriage, and gender equality as some of the main areas that will be poorly affected by the state of the education system.

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. Photo: IPA

UN Secretary-General Antonio Guterres. Photo: IPA These gloomy forecasts refer to a situation where programs for school excluded youth remain active. In Israel, these programs include the education ministry’s HILA Program, which, like other similar programs, is currently facing termination due to budgetary issues. Should this happen, the effect on at-risk youths will be even greater.

HILA is the last resort for pupils who have dropped out, according to Walid Taha, a member of the Israeli parliament (the Knesset) on behalf of the Joint List, which includes the country’s four major Arab-led parties. “If the program is shut down, these kids will have nowhere else to go besides the street,” Taha said.

The expected shut down of the program is not caused by a lack of money. The cost of its continued operation for the remainder of the budget year is NIS 1.5 billion (approximately $440 million) and, according to Galant, the money is available. However, as a state budget has yet to be approved, there is no legal way to allocate new funds to the program.

Galant places the blame on Alternate Prime Minister Benny Gantz’s refusal to pass a new budget for just one year. In forming the current government, Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu agreed to pass a bi-annual budget at Gantz’s demand but is now backing down and pushing for a single year budget in what many see as an attempt to send the country on yet another election, the fourth in under two years. What is clear is that tens of thousands of youths might become collateral damage in Netanyahu’s political exploits.

The Arab minority did not go back to school

The risk of pupils dropping out is far greater for members of the Arab minority in Israel, who amount to around 20% of the population, as the Arab education system has yet to resume full activity since the lockdown was lifted in May.

Attendance in Arab educational institutes in the period that came after the lockdown was at just 10%-30%, according to Sharaf Hassan, chair of the education committee of the High Follow-Up Committee for Arab Citizens of Israel, an extra-parliamentary umbrella organization that represents Arabs with Israeli citizenship at a national level. For comparison, in May, the Ministry of Education reported 75% attendance at Jewish educational institutes.

Arab Children enter their school. Photo: Amit Shabi

Arab Children enter their school. Photo: Amit Shabi The ministry fails to maintain a dialogue with the Arab minority, Hassan told Calcalist. “We asked for meetings, but got no response,” he said.

Hassan is convinced that the already prolonged absence from school will significantly increase the dropout rate. “Anyone who hasn’t been to school since March has effectively already dropped out,” he said.

Academically, Hassan said, the damage already done to first and second graders will stay with them throughout their lives. “Arab pupils lost a school year as most of them were unable to attend remote classes,” he said. “If this year is disrupted as well, they will lose two consecutive school years.”

As an underprivileged population, Hassan said, the Arab minority in Israel has a dominantly large number of at-risk youth and should programs intended to handle dropouts be shut down due to political budget issues it will result in a disaster.

“You can already see an increase in crime, caused by youths roaming the streets aimlessly all the time,” Marian Tehawkho, a senior researcher at the Aaron Institute for Economic Policy at the Interdisciplinary Center Herzliya (IDC), told Calcalist.

"There is a severe trust crisis as Arab parents feel the education ministry had abandoned them,” Hassan said. “Half the schools in the Negev region, for example, operate in makeshift structures and 50,000 students rely on bus transports that are extremely crowded,” he explained.

In predominantly Arab city Nazareth, Hassan added, classrooms are also extremely crowded, with 40 students each, making it impossible to maintain social distancing. On top of all of this, he explained, high unemployment rates among the Arab minority also mean many parents prefer to keep their children at home.

Galant is not blind to the disturbing phenomena of Arab parents boycotting schools but, instead of turning to his own ministry, decided to shift responsibility to Arab members of parliament, calling on them in a Knesset meeting last week “to encourage attendance by Arab pupils, as much as they can.”

Digital gaps will grow dramatically

The combined back-to-school outline is also likely to increase the social gaps between Israeli pupils. Israel entered the coronavirus crisis in very bad shape in terms of academic gaps between pupils from its top percentiles and those from lower percentiles.

The OECD’s 2018 Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results put Israel in the unfavorable first place among participating countries in terms of the divide between the strongest and weakest students. These sad results are due, in part, to Israel’s unflattering place in other OECD rankings—fourth in the poverty rate of families and second in the poverty rate of children.

Shifting to distance learning, whether it is for the entire school week or just for a part of it, will dramatically widen these gaps as the weaker populations in the country have far less access to computers and internet connections and lack the necessary digital literacy.

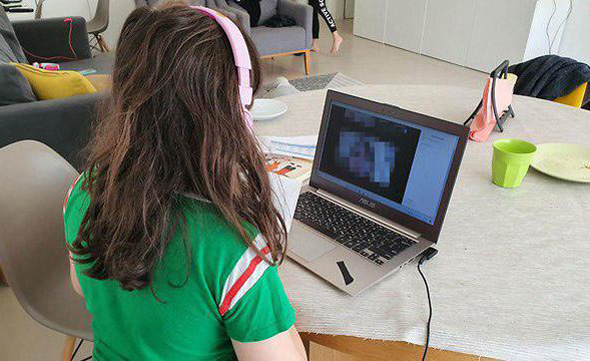

Remote learning. Photo: Adi Ben Ami

Remote learning. Photo: Adi Ben Ami Stronger schools have better infrastructure to support online learning and they can also hire additional teams to help children cope with the change and make sure they are learning, according to Tomer Samarkandi, executive director of the Israel Scholarship Education Foundation (ISEF), a nonprofit dedicated to promoting students from underserved backgrounds. Parents with more means can pay for tutors, Samarkandi told Calcalist, and, in the end, the real price will be even wider socio-economic gaps.

As with many other shortcomings, the mishandling of the digital gap in the five lost months since the shutdown of the Israeli education system can only be regarded as a failure by the system.

Former Minister of Education Rafi Peretz—who assumed office in June 2019 only to step down in May this year—promised, at the time, that NIS 50 million (approximately $14.7 million) will be allocated for the purchase of computers for students. In the end, the project received a budget of just NIS 16.5 million (approximately $4.8 million) and, according to the Knesset Research and Information Center, just 7,000 computers were actually distributed to students. A drop in the ocean.

Now, new promises are being made. Israel intends to spend NIS 1.2 billion (approximately $353 million) on promoting communication and connectivity in its education system. Of this sum, NIS 500 million (approximately $147 million) is intended for the purchase of 144,000 laptops equipped with Microsoft Office and sim cards with cellular internet support for those pupils who live in towns that have no internet infrastructure.

In addition, the ministry intends to purchase 64,000 Kosher cell phones for ultra-Orthodox (Haredi) pupils, as distance learning within this community is done through voice calls.

The equipment will remain the property of the educational institutes, which will loan it to students for the duration of the Covid-19 crisis, to prevent the possibility of impoverished families selling it to pay for other expenses.

Of the budget, NIS 700 million (approximately $206 million) is intended for purchasing filming, broadcast, and screening equipment for the schools themselves, as well as for teacher training and fiber optic internet connections. “It is far more than we did in all of the last decade,” Ofer Rimon, deputy general manager of technology at the Ministry of Education, said. “As far as I am concerned,” he said, “this is the ideal plan.”

Students and their laptops. Photo: Tal Shachar

Students and their laptops. Photo: Tal Shachar But, even this “ideal plan” is full of holes. According to Galant’s promises, only half of the laptops—72,000 units—will be purchased by the end of January 2020. This means that even after mass production of vaccines is expected to begin in Israel and around the world, there will still be tens of thousands of families in the country without a single computer.

Galant estimates that things will be much better in the next school year, which starts in September 2021, but, by then, there will likely be no distance learning.

The ministry of education estimates that there are currently 95,000-117,000 school-age children that do not have a computer at home and its aspiration is to have at least one computer per household.

The Ministry of Finance, on the other hand, has very different numbers. According to its analysis, around 20% of students—some 500,000 children—live in a computer-less household, and 27% of students have no internet connection at home. It is safe to assume that a large share of these students are Haredi children whose parents do not want to have a computer in the house for religious reasons. Still, it is unlikely that 144,000 computers will be enough to bring a computer into every household that needs and wants one.

This plan, even if and when it materializes and is successful in bringing a computer into every household in Israel, would still not solve the issue of hundreds of thousands of siblings that will need to share a computer while using it to attend classes happening simultaneously. The government’s plan does not even refer to this situation.

According to the 2018 PISA survey, around 18% of non-Haredi students in Israel only had one computer in the house. All in all, this amounts to 150,000 pupils with access to just one computer per-household, accounting for 30% of Arab students and 14% of Jewish students. This means that, even in the best-case scenario, children from underprivileged communities who have siblings, would miss another year of school.

According to the education committee of the High Follow-Up Committee for Arab Citizens of Israel, the situation is even graver among the Arab minority. The committee estimates there are 140,000 students, among the Arab minority alone, who don’t have a computer, nearly the same as the total number of laptops the state intends to distribute. The numbers were collected from towns and villages in which 50% of the Arab population resides and were then doubled to create the estimate.

Another population with an even more severe problem is the children of asylum seekers and foreign workers, around 6,100 children enrolled in the system, 94% of whom were already born in Israel. These students do not have a computer or an internet connection at home, according to Iris Ben David-Hadar of the School of Education at Bar Ilan University. These children cannot even use their parents’ smartphones, as due to their legal status they rely on expensive pay-per-use data plans, she told Calcalist.

Teacher training is out for the summer

Even if the Ministry of Education does acquire the necessary electronic equipment, it will not be enough, as teachers need to learn how to use it. While most teachers have likely learned, by now, how to operate the basic functions of Zoom or similar tools, experts agree that simply taking a frontal class and conducting it online as-is makes learning far more difficult and misses out on the many advantages of distance learning. For online classes to be productive they must include interactive activities, group work, exploration, and debates. A teacher talking on tape for 45 minutes just won’t cut it.

Teaching a lesson on Zoom. Photo: YNet

Teaching a lesson on Zoom. Photo: YNet

Asked what he thought of Israel’s fast transition towards distance learning, Andreas Schleicher, the OECD’s director for education and skills, told Calcalist last month that he wouldn’t really call it that. “Much of it was 20th-century teaching using 21st-century technology,” he said at the time. “Distance learning is a little more than conducting online lessons. An innovative learning environment can only be achieved with teachers working together, developing technologies together, and sharing from their joint experiences,” he explained.

The Ministry of Education failed to use the summer vacation for training teachers to use these systems more optimally. There were some optional courses for teachers but most of the faculty will start the new year with exactly the same skill set they ended the previous one.

In an appearance at the Knesset, Rimon pledged that the education ministry will offer 7,200 30-hour courses for teachers and school staff during the next school year. These professional courses will try to give educational teams the tools to help children learning remotely to progress. The problem with this plan is that the courses will only be completed in six months. Still, there is room for hope that we will see gradual improvement as they progress.

This is another aspect in which the Arab minority is doing even worse. “They hardly learned anything even when online classes were available,” Tehawkho said. According to a survey conducted by the Aaron Institute, 70% of Arab teachers in Israel do not know how to operate Zoom, even on the most basic technical level. According to Tehawkho even teachers that know how to launch the app usually don’t know how to converse with students. “This type of teaching is completely ineffective,” she said, “if they don’t offer training for teachers, no one will learn anything in the Arab education system next year as well.”

Blocking out change

The coronavirus crisis marks a huge missed opportunity for the Israeli education system. Earlier this month, Ya'akov Margi, a member of the Israeli parliament on behalf of Haredi party Shas who previously headed the Knesset’s Education Committee, accused the education ministry of preventing any initiative for change.

“Covid-19 was an opportunity,” Margi said earlier this month at a meeting of the committee, “anyone that works in education, except those within the ministry, think it is time to revolutionize Israel’s education system. I finished my run in the system 40 years ago and my son graduated two years ago and hardly anything has changed.”

Now, Margi sees the current situation as an opportunity for innovation but feels the system is broken and that those at the top must get themselves together and start thinking outside the box. “They don’t see what everyone else is seeing,” he said, “either that, or they are afraid of change.”

Taking all of these elements into account, it appears the least the education ministry should do is prepare, as early as possible, a plan for minimizing gaps between students once the crisis is over. This plan should include identifying dropouts and assimilating them back into the education system, tutoring, and the option to repeat the twelfth grade, at no additional cost.