Interview

Co-founder of Team8: “Success requires that the stars align for you. We know how to align them”

In the seven years since his discharge from the command of the Israeli army’s elite intelligence Unit 8200, Nadav Zafrir has turned Team8, the cyber company group he established, into a mini-ecosystem. Now he’s warning about the gap exposed by the coronavirus pandemic between cyber attacks and the defense systems meant to repel them

For the past six months, Nadav Zafrir, founding partner of the cyber company group Team8, has been stuck at the group’s office in New York – and the return flight to Israel is nowhere on the horizon, due to the vagaries of the coronavirus pandemic. “Both as people and as managers of an organization, we’ve been through several upheavals,” he says.

“In February, the feeling was that it had nothing to do with us; in March, after the transition to working from home, there was almost hysteria; and then, after we realized that the sky didn’t fall down, many organizations moved into a state of euphoria. Today we understand that we have a long-term event that will harm all of us. I believe we still need and want human interaction, so the question is how long can we hang on like this.”

Nadav Zafrir, Team8 Co-founder. Photo: Nadav Neuhaus.

Nadav Zafrir, Team8 Co-founder. Photo: Nadav Neuhaus. Zafrir knows a thing or two about the realm of cybersecurity and about taking action during crises on a wider scale: He served in the Israel Defense Forces’ elite units, was decorated with the Chief of Staff’s Citation and commanded Unit 8200, the IDF’s well-known military intelligence unit that is recognized as one of the world’s best cyber academies. This expertise has served him well: Team8 and its companies have recruited over 100 employees in 2020, and Zafrir predicts that the group will finish the year in better shape than it started it.

Nevertheless, the turmoil caused by the pandemic forced Zafrir to come up with a new path for Team8. The company established a working group to analyze the current crisis and the new cyber risks it created, and the resulting conclusions were worrisome: the overnight transition to working from home (WFH), based on a digital infrastructure that was not designed to support what it’s doing now, has stretched the existing systems’ capabilities to the breaking point.

The result is a “cyber debt,” as Zafrir has dubbed it. “The risk of attacks increased and the ability to contain them has taken a significant hit. For example, companies can’t allow themselves to not paythe perpetrators of ransomware attacks. The attackers have identified this opportunity and are exploiting this period to create bridgeheads, so we can assume that we’ll be seeing much more sophisticated attacks in the near future. All of this adds to the prevailing chaos.”

Former Mossad chief Tamir Pardo recently warned that the pandemic would lead to a change in the world order. Is this also relevant in the digital realm?

“Yes, our reliance on the digital space and on new opportunities is dangerous not only in the commercial context. We’ve already been undergoing a digital transformation for decades – some of what we expected to happen in 2030 is happening now, but we haven’t had time to match our defense systems to this acceleration, and the gaps are only increasing. At the same time, the coronavirus also challenges globalization: organizations, countries and the intersection between them will leverage our reliance on the digital infrastructure in adverse ways, spanning from surveillance to actual weaponization.

“As the election in the United States draws near, the concept of “digital trust” and the confidence in our digital infrastructure goes from important to critical, and at the same time we are seeing commercialization of capabilities that challenge this. It’s already possible to create bots that will cause you to doubt whether it’s me that’s speaking to you, and not my bot. In addition, we’ve transferred some complex and critical decision-making to machines, but they are exposed to attackers and can be manipulated. So in a situation where everything is digital, digital security is crucial and is eroding.”

You’ve presented a picture of a gloomy situation while at the same time broadcasting optimism.

“The question is from which angle to look at reality. The digital infrastructure enables the continuation of a new normal, and that’s positive. Take the current situation, take out the internet and you’ll get 1918, when you couldn’t send people home (to work – ed.) because everyone would die from hunger. The digital infrastructure enabled resilience. The pessimistic side is that we’re more fragile.”

“The kids wanted us to open a candy store”

Zafrir spent a considerable part of his childhood in Latin America (his father was a diplomat) and returned to Israel in 1988 to enlist in the IDF. He began his military service in elite secret combat units and ended it as Commander of Unit 8200. “I never planned to have a military career, but for me, the army was an amazing experience,” he says. “At every stage when I was thinking about leaving it, I got a more challenging offer. The IDF put me through university, and it was in the army that I met my wife and some terrific friends. People like Guy Sela (the founder of SolarEdge who died from cancer in 2019 and was Zafrir’s commander – ed.), who taught me about curiosity and overcoming fear, and extreme agility.”

- Team8 launches new fintech startup founding platform, targeting $100 million in investments

- Team8 raised $30 million for a new fintech fund

- Payoneer founder and president Yuval Tal to step down and join Team8’s fintech fund

Team8 was founded in 2014. “It started when I was on a train from Washington to New York with Israel,” he says, referring to co-founder Israel Grimberg, who served as the Head of the Cyber Division in Unit 8200. “Israel was due to be discharged a week before me, and I asked him what he was going to do. At that time, both Israel and I had young children and my kids wanted me to open a toy store or a candy store. Israel said he had an idea related to the wisdom of the crowd, in the context of startups and innovation. I asked whether he’d like to do it together and that’s how we decided, three weeks before our discharge.”

You left the IDF rich in knowledge and experience. It could be assumed that you got some tempting offers, and yet you chose to set out on a new path.

“I didn’t want to work in a gigantic organization or in security services. I didn’t want to have to hide what I do from my kids.”

The concept the pair put together was founding a group that would establish startup companies in the field of cybersecurity and make the first investment in them. They quickly discovered that the local ecosystem did not share their enthusiasm. Their resumes did open some doors, “but after we explained what we wanted to do, most of them threw us out,” Zafrir recalls. “Then one day my wife came home and said she had heard some people discussing cyber at a café near our house in Herzliya (a major high-tech hub just north of Tel Aviv – ed.) and suggested I speak to them. She was probably afraid I’ll be stuck at home with her.”

The person leading that conversation in the café was Yuval Shachar. “He had just founded the Marker LLC venture capital fund and he had already sold three companies to Cisco. That café was his office. When Israel and I finally met him we mentally prepared ourselves for another rejection, but after we finished speaking with him and presenting our idea, Israel and I decided that if we were already in a café, why not have lunch. Yuval wrapped up another meeting, came over to us and said the idea was actually interesting, that he’d once thought about doing a similar thing with Cisco. Later in the process, Israel and I were joined by another two Unit 8200 graduates: Liran Grinberg, who took only 30 minutes to say yes to joining us, and Assaf Mischari, who was discharged a year later. This is the 8200 gang.”

Team8 operates according to a unique model on the local scene. The group has a wide-ranging team whose job is to think about challenges and solutions in the field of cybersecurity, plus a group of investors and partners who serve as the “test group” that examines these ideas, referred to as the Team8 village. Initially, each idea is carefully researched and validated by a small team until it reaches the stage where it gets an initial investment from Team8 in exchange for 50% of the equity, a very high rate for a seed investment. So far the group has had only one exit with Sygnia, which was acquired by Temasek in 2018 for $250 million. Team8, which put $4.3 million into Sygnia, was the company’s sole investor.

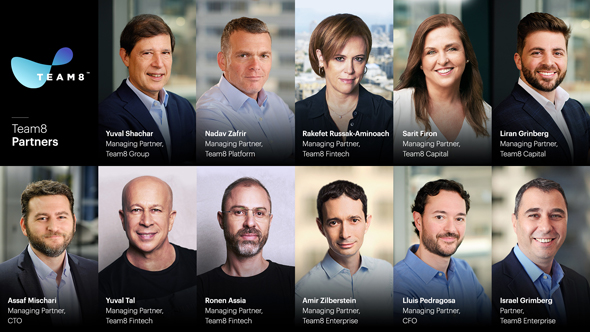

The Team8 partners. Photo: Scott Wagner, Jonathan Bloom and Ron Kedmi

The Team8 partners. Photo: Scott Wagner, Jonathan Bloom and Ron Kedmi In June, Team8 announced the establishment of a new VC fund headed by Sarit Firon, one of the first investors in Datorama (in which she was joined by Liran Grinberg). This week, Team8 announced the launch of a sister foundry group in the field of fintech, headed by Rakefet Russak-Aminoach, former CEO of Bank Leumi; Yuval Tal, co-founder of Payoneer; Galia Beer-Gabel, former regional head of business development at PayPal; and Ronen Assia, co-founder of eToro.

“I’m proud of what we’ve achieved, but I believe we’re at the beginning of our journey,” Zafrir says. “Our aspiration is to take the process of building high-tech companies, which started in the 1970s in Silicon Valley and hasn’t changed much since, and improve it. Our ambition is to create something unique and widen it out, not only to cyber but also to fintech and other focus areas. What we’ve achieved is significant, but the jury is still out and we have a long road ahead to prove our model.”

Seven years have gone by since you started out. Have you changed since then?

“Absolutely. I wanted both to achieve financial security and to reinvent myself, in the sense that I would be an expert in my field and be in a situation in which I deeply understand the language and the processes. It took me half a year to understand the concepts, and another two years to start speaking the language. Israel and I always compared this with basic training, boot camp etc. We are, and hopefully will remain, in a constant learning mode.”

How my biggest successes have been just one step away from failure

Over the years, Zafrir has spoken little about his military service. Today, too, he declines to reveal, for example, why Chief of Staff Shaul Mofaz awarded him the Chief of Staff’s Citation. “I received the citation because the event succeeded, but it was a hairline away from failure. There’s a tendency to disparage failures, not to identify the parameters that lead to it, but it must be remembered that often success included a disproportionate amount of luck. A long-distance runner standing on the podium knows how many times during the race she or he was just a split second from giving up.”

How does it feel, getting the Chief of Staff’s Citation?

“I was very happy; everybody likes to be commended. But I hope I have the ability to put things in proportion. In his book ‘The Old Man and the Sea,’ Ernest Hemingway wrote: ‘It is better to be lucky. But I would rather be prepared. Then when luck comes you are ready.’ I had a disproportionate amount of luck in my service in certain events that could have ended in a different way.”

Is it the same in tech?

“Yes, although with startup companies you’re not dealing with people’s lives, but rather with dreams and investors’ money. In the army or in high tech, you have to remember that in most cases history is told by the winners. But when you succeed in selling a company or a product, or in raising capital, it’s not because ‘that’s the way you are,’ but rather because you worked hard and also had some luck. The difference between success and failure is sometimes minuscule.

“That’s what we at Team8 try to do for our companies: The entrepreneurs don’t work for us; rather, we work for them. When required, we will roll up our sleeves and try to go beyond advice and guidance; if there's a competitive hiring situation, for example, we’ll do whatever it takes to succeed in hiring and by doing so improve the overall probability of success. Ultimately, success requires that many stars align, and our goal is to help align the stars. We try to prevent avoidable errors,’ the mistakes you make because you created them yourself and not because the world gave you a slap in the face.”

“The synergy between the IDF and the economy is fantastic”

The approach Zafrir brought to Team8 was based, at least at the beginning, on “graduates” of the IDF’s elite intelligence units, 8200 and 81. But he admits that this in itself wasn’t enough, so he beefed up the group’s capabilities by adding partners and advisors from other fields. “I acknowledge my shortcomings and the limits of my experience,” he says. “People like Yuval Tal, who built Payoneer, have abilities I won’t attain for the next 50 years.”

Nonetheless, your worldview was fashioned in 8200.

“One of the important things I took with me from Unit 8200 is a worldview that verges on meritocracy, in which it doesn’t matter where you grew up and where you were educated. The unit taught me that if you create the right infrastructure and trust, and portray that failure is not the end of the world, everything is possible. These are the things I take with me everywhere, and certainly to Team8 and our companies.”

- Israeli tech companies sell too soon, says Koch Industries exec

- COVID-19 to boost the insurtech revolution: An exclusive Interview with IDI CEO Kobi Haber

- Israel must double down on exports amid Covid-19 crisis, urges export institute chairman

There is a growing public feeling that serving in Unit 8200 is a springboard to a career in high tech and not a place that recruits choose out of a sense of mission.

“There’s no doubt that for those who’ve ‘graduated’ from 8200, the first steps in civilian life are easier. But don’t underestimate the personal strength and leadership qualities of someone who took the combat service path. An individual who enlists in a combat unit at the age of 18, goes through a grueling journey and persists gains something truly unique. Technology and programming can be attained later, but the character-building and personal coping skills and leadership can’t always be replicated. Some of the people at Team8 have combat experience, and although it’s true that I didn’t recruit them only because of it, I believe they got to where they are today because of their military service. I did both (combat and technology – ed.) and I wouldn’t change my path.

“Unit 8200 makes a huge contribution, first of all to the IDF but also to the country as a whole. What takes place in the technological units is becoming ever more relevant. For instance, in telecommunications infrastructure: There is a blurring line between military and civilian capabilities. We witness the relevance of capabilities that were built in the military extended into the business world and unfortunately also into criminal groups. This relevance wasn’t created because the unit thought that’s where the economy was heading, but because it was essential, yet the positive economic trickle down effect is a big plus.

“There are two basic things the unit did right. First, it realized that there really are people with innate abilities and that they are everywhere, and if we know how to identify them, their contribution will be fantastic. Among other things, we give a second chance to people who didn’t fit in at school. The second idea – one that has been challenged quite frequently – is to be liberal about allowing these units’ graduates to leverage their military technology education in the startup world. This creates a fantastic synergy between the IDF and the Israeli economy. We at Team8, for example, are very proud that we continued to recruit during this crisis and obviously when we have a successful acquisition or IPO we continue to give back to the country via taxes. I’m guilty of being profoundly Zionist.”

“In the coronavirus era, technology prevents collapse”

These days, the pandemic is shedding a genuine, unvarnished light on the promise of communication technologies and artificial intelligence, resulting in the exposure of a great many limitations. Zafrir, however, hasn’t lost faith. “Don’t diminish the value of the infrastructure that allowed people to start working from home, almost overnight,” he says. “It’s really astonishing. Without this infrastructure, we’d be caught in a catastrophe of a completely different nature.

“Regarding artificial intelligence systems, we are in a unique situation. At the end of the day, training these systems is done by providing them with access to historic data in order to reach conclusions about the future. In cybersecurity, for instance, a unique situation has been created in which actually there isn’t enough historic data since this is truly an unprecedented situation. I’m not an expert in epidemiology, but the movement toward the rapid attainment of a vaccine is moving at a much quicker pace, thanks to technology.

“The fact that the banks are still working, the healthcare system is working and people are making Zoom appointments with doctors and entire systems did not break down – in my view, it’s a small miracle. And it’s thanks to the resilience of the digital infrastructure we have built over the past 30 years.”

But technology has also produced some problematic solutions. In terms of the coronavirus, it’s the choosing of surveillance and location trackers.

“Israel chose health over privacy, and our place as technologists is to solve that dilemma. This is exemplified in the new encryption capabilities of Duality, one of our portfolio companies. They’re working on this very topic now and they have the ability to transcend these dilemmas, in this case via homomorphic encryption allowing computation on encrypted data. This is crucial to align and create a new balance between privacy and other considerations such as health.”

Until then, it’s liable to be too late.

“I understand the frustration, but we need to look into this in a balanced way. This is a challenge like we’ve never experienced before. We are still in the midst of the crisis. This is not the time to despair. We have to assess what we know and create a balanced approach to reduce the risks. Do all countries do this well? Certainly not. Are technology companies partners in reducing the potential damage? Unequivocally yes.”

- Back to normal: 8200 Impact accelerator program launches in physical space

- Unit 8200 veterans accelerator gets new head in Yarden Abarbanel

- Unit 8200 Commander Attacks Cybersecurity Startup That Tried to Poach Soldiers

What is the biggest mistake that was made in dealing with the pandemic?

“In every crisis of this kind, the most important thing is the question of when’s the optimal time to make difficult decisions. On the global level, the mistake we made is not designating the point when it was best to take the difficult decisions. Sometimes you have to finally arrive at a decision in the face of a changing reality.

“The second thing is to create cooperation and partnerships. There are issues here about privacy and regulation and politics. So next time there will be more extensive cooperation, and that brings us back to the question of trust and security.”

There was a lot of separation and competition among various countries. Not cooperation.

“In most competitions, there are situations in which your enemy stumbles and the advantage goes over to you. In this case, there’s no doubt that this is utterly foolish. This is not the time for a zero-sum game mentality. A local solution would be meaningless.”