Interview

Delegating the IIA to a government ministry would be an act of madness, says outgoing CEO

After four years at the head of Israel’s tech investment arm, Aharon Aharon shares his successes and failures

10:1702.10.20

"A vaccine for Covid-19 is complicated. No one has ever developed a vaccine or anything close to it in Israel so to think that we will be the ones to develop a global vaccine for coronavirus is nonsense. That won't happen," the outgoing CEO of the Israel Innovation Authority (IIA) Aharon Aharon told Calcalist.

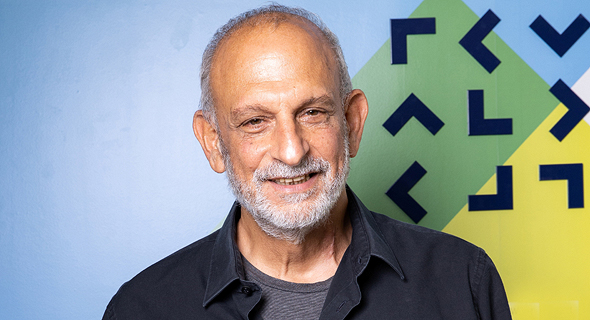

IIA outgoing CEO Aharon Aharon. Photo: Alex Kolomoisky

IIA outgoing CEO Aharon Aharon. Photo: Alex Kolomoisky

At the end of August, Aharon surprised the local tech industry with the announcement that he would be resigning. He said he would continue in the role until a replacement is found, which is only expected to happen towards the end of the year. "I was always thinking about when would be the right time to retire. I thought about retiring in March, but Covid-19 changed that. My eventual timing was also not great as it coincided with the resignation of the head of the Budget Department at the Finance Ministry Shaul Meridor, but I understood that it was time for me to leave."

Aharon was appointed to the role at the end of 2016, shortly after the IIA became an independent body, replacing the Office of the Chief Scientist at the Ministry of Economy. He had previously served as VP Hardware Technologies and GM of Apple Israel as well as in senior executive positions at IBM Israel. His departure has raised concerns that his replacement will be weak or politically motivated.

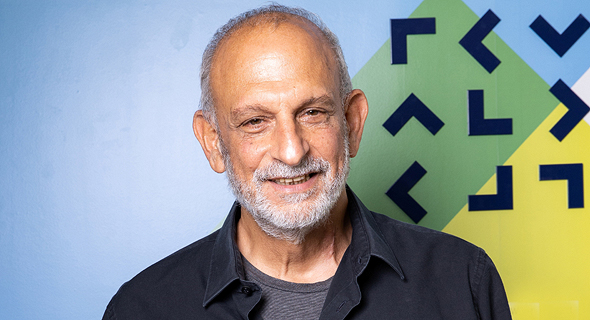

IIA outgoing CEO Aharon Aharon. Photo: Alex Kolomoisky

IIA outgoing CEO Aharon Aharon. Photo: Alex Kolomoisky Who do you think should replace you?

"At all my previous roles I selected my successors and was involved in the entire process. The IIA has completed its move to Jerusalem, during which it saw its workforce downsized by 90 people. The management has remained stable and the challenges my replacement faces will be different to the ones I had. They will have to be able to run a complex, multi-dimensional organization, have excellent interpersonal relations, especially as that is a basic requirement in order to get along with the government. They will also have to be well known and well respected so that people won't question their abilities."

Minister of Science and Technology Izhar Shai thinks that the IIA should be delegated to a government ministry.

"We are an independent unit. We used to be part of the Ministry of Economy but now that we are independent we have much better work relations with them. I’m friends with Izhar and I think he has a good overall vision, but to make us part of the government again would be madness. There are many pressures coming from the government, but we are able to resist them because we are an independent organization. If we were part of the government that wouldn't happen. Tech is like lava, it will continue to flow even if you try and block it. We are looking for the problems that are blocking the flow of the lava and removing them."

How did the tech industry respond to the Covid-19 pandemic?

"Two things happened during the crisis: there was a yearning for technology and digital transformation. Both are wonderful for tech and the question is who benefits from it. Around 10-15% of the tech companies received a boost from the pandemic. It is amazing to see where JFrog and Wix were before the pandemic and where they are now. There are companies that shouldn't have even existed, but in an industry that is prospering they somehow managed to survive and this is true for about 10% of the companies. Then there is the rest, which is the majority, that suffered a big blow in the crisis. We are trying to help them but want to avoid investing good money after bad. In our fast track route, which we set up during the pandemic, we vetted the quality of the company, whether it has enough money to survive, if its management reacted well to the crisis and displayed flexibility and whether it has good financial potential.

"None of us initially understood what this crisis was. At the beginning of the crisis in March we assumed that it would be over by the third quarter of 2020 and that the economic recovery would soon follow. But our assessments have undergone major changes."

One of the IIA's biggest projects is aimed at getting local institutional investors, meaning pension and provident funds, to invest in Israeli tech. The project is gathering steam, with the 10 institutional investment firms that will benefit from the program being selected on Wednesday. Those who object to the plan, claim that the institutional investment firms charge too high a commission and that there is a danger of creating a bubble that will burst. Those in favor of the program claim that it makes no sense that a pension fund in New York is benefitting from investment in Israeli tech while local pension funds are wary of doing so. Aharon and the IIA believe the move is essential and that is why they set up several programs to promote it, including recruiting analysts for the different firms before also offering a safety net to institutional investors that will entitle them to receive back up to 40% of their original investment from the state in the case of losses.

Why is it so crucial to you to get the institutional investors involved?

"I was looking at the different investments made by the institutional firms over the past 10, 15 and 20 years. If these firms had invested in tech, savers would have been in a far better state. Savers received lower returns because the funds didn't invest in tech. They invest 97% in state bonds and we are talking about the remaining 3%. That money is currently going to local tycoons like Yitzhak Tshuva and Nochi Dankner, which is far worse than tech and far less stable. Why does the pension fund of the employees of the State of California benefit from Israeli tech by investing in local VCs while the citizens of Israel don't have the right to benefit from local tech? That is a market failure.

"In our analyst program we saw that the institutional firms that didn't have an analyst and didn't receive funding from us to hire one still decided to hire one themselves. That happened a year-and-a-half ago. Our program will not fund losses. It will cover up to 40% of losses over 10 years or will benefit from 10% of successes. I can already hear the institutional firms discussing tech investments. This wouldn't have happened without government money. I hope that five years from now we'll see institutional investors invest intelligently and probably do so in a much broader manner than we defined for them. We will see them invest in very late stages and in very early stages. I think it is excellent that Israeli tech will be using Israeli money and not just American money."

When you sum up your tenure, what was your greatest success?

"I think it was the fast track we developed during the Covid-19 pandemic. It encapsulated everything that we have developed here. We managed to build a funding fast track to save companies within a month, when we needed two weeks just to receive ministerial approval. We have so far invested NIS 500 million ($146 million) and that will increase to NIS 650 million by the end of the year."

What is your biggest failure?

"There were many failures. We didn't succeed when it comes to the periphery the way I had hoped. I come from the periphery. I've lived in the Galilee for the past 35 years and despite all our efforts we didn't succeed there. There are around 3,000 engineers in Beer Sheva and that is not a great success. We invested a lot of money there and it didn't succeed. You need to build an ecosystem and bring about a big change. The IDF's move down south was the big change that was supposed to happen but it never materialized. In a small country like Israel there is no need for any more than one metro area and Tel Aviv serves that purpose. There are three sub-metro areas in Beer Sheva, Jerusalem and Haifa. The problem with all three is that they see themselves as competition for Tel Aviv which is a bad mistake. Beer Sheva should look to the south and the east, but instead it is looking at Tel Aviv. The same goes for Haifa and Jerusalem that are all trying to be like Tel Aviv. That is complete nonsense as in a country like ours there can only be one tech metro. I put a lot of energy and effort into this and was very far from succeeding."

What about the integration of women, and the Haredi and Arab sectors?

"The integration of women in tech is a failure. If you look four years back there has been no change. There are more female entrepreneurs, but at the macro level we didn't succeed. Regarding Arabs and Haredim, we are moving in a very positive direction, but the results are still not there. From 2012 to 2018 the number of Haredim in tech rose from 3,400 to 6,900 and that is a massive rise. We are also seeing excellent results with the Arabs. Arab graduates of the Technion are getting jobs at Apple and Intel, which wasn't previously the case. The problem is that most Arabs live in the periphery and therefore they settle for positions that are located nearby and then their salaries are lower. If we manage to create enough jobs in the north this problem will diminish, but unfortunately I don't see the periphery blossoming."

What do you think of work from home that has become the new normal during the pandemic?

"It has some positive sides, but also presents a difficult problem as the innovation that was born out of personal and informal meetings in companies has suffered a big blow. It is very difficult to create innovation when you are at home by yourself. Innovation comes from informal meetings between two employees at the office kitchen and companies must find a way to deal with this."

What are you planning to do next?

"I want to do something different. I have countless offers and I'm telling everyone that I'll decide after the Jewish holiday season, but I still don't know what I'll do."