Interview: The Koch empire’s man in Israel who has unlimited funds to invest in tech

Eli Groner has a history of working for controversial figures - from Benjamin Netanyahu to Charles Koch

“The government must refrain from interfering,” Groner explains. “It should just lower taxes so that hardworking people can keep as much money as they can without it going to inefficient needs.” It is somewhat of a surprising statement considering Groner’s substantial time in public service, most notably as the Director-General of the Prime Minister’s Office during the tumultuous years when Benjamin Netanyahu pushed through the much-opposed outline for natural gas drilling. But after leaving the post on a sour note in 2018, Groner changed course, preferring to revolutionize the tech sector: “It was clear to me that after leaving the government I’d turn to tech. The values of liberty, self-actualization, and reliance on people rather than governments for solutions have found solid footing in the tech sector.”

Eli Groner. Photo: Tommy Harpaz

Eli Groner. Photo: Tommy Harpaz For the past two years, Groner has served as the managing director of KDT (Israel )(Koch Disruptive Technologies) the innovation arm of Koch Industries, America’s second-largest private company that deals in everything from oil refineries to mineral water to toilet paper, and employs 130,000 people in 70 countries.

KDT is an outlier in terms of investment funds: most investment bodies, even the biggest and strongest, have a cap on the sums they can invest. But Chase Koch, Charle’s son and Groner’s direct boss has set no such limits, not on the amount, not on the company’s field of operation, and not on the company’s stage of growth, instead instructing him to simply “find the best companies and invest in them.”

“We are the most flexible money you’ve ever seen in Israel or the U.S.,” Groner says proudly. “We invest out of the balance sheet and seek significant disruption. We aren’t structured like a fund, there is none of the capital allocation or limitations that a venture capital fund has. We invest out of the balance and seek significant disruption. We are not focused on a single sub-sector or growth stage. Koch itself started in energy and is now involved in 60% of the U.S. industry. The only limitations are my own capacity and that of my team. For now, the team is me and one more person, but we’re recruiting a third.”

Since it began operating, KDT’s small team has invested no less than half a billion dollars in five Israeli companies. It started with a $300 million investment in Insightec Ltd., a developer of MRI-guided ultrasound devices, and then led four investment rounds, in which it made up 80% of the total money raised: $109 million in 3D imaging sensor company Vayyar Imaging Ltd.; $71 million in rapid blood-testing startup S.D. Sight Diagnostics Ltd.; $45 million in proteanTecs, the deep data company founded by former Mellanox executives; and $2.5 million in Deepcube, which developed a deep learning solution for software upgrades. KDT is currently leading its sixth investment that will make up $25 million of a total $40 million round in a new company. KDT’s Israel activities are the only ones outside of the U.S. and its investments in Israel make up half of its investments worldwide. In fact, in two years of silent operations, which took place nearly entirely under the radar, Koch Industries invested in Israeli tech the amount that a large local VC fund invests over five years or more. It appears that for Groner, however, $500 million is just the warm-up ahead of the Koch family’s major charge on the Startup Nation.

It sounds like you’re a type of Softbank — an organization with deep pockets that wants to disrupt the local investment scene.

“Really, we’re not. What’s special about us is that we invest for the long term. We want to build giant companies here. That’s the beauty of a private entity with only one partner.”

No investors, no limitations, how will your success be measured? Is there at least an expectation for annual ROI?

“Chase forbids us to look at the IRR (Internal rate of return) because looking at it encourages short term thinking. IRR makes people limit their investment to five years instead of six or delay the investment and hold on to the money six months longer to artificially increase ROI. We won’t do anything that distorts the result since we assume that the entrepreneur’s long-term interest is the right one and if we try to help them, it will eventually build up our reputation.”

What are the measures of success?

“We look at the company’s valuations relative to the capital that was invested and trace the company’s development. We want to build huge companies here.”

$400 Million To Fund A Far-Right Shadow Government

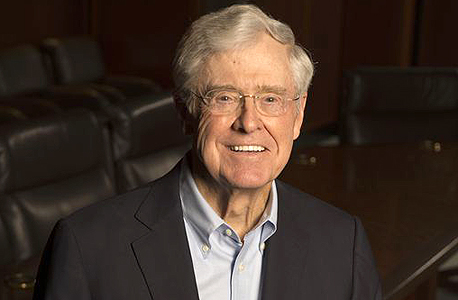

The Koch family fortune is estimated at $120 billion, making it the U.S.’s second-richest family. Forbes ranked Charles Koch as the 15th richest man in America. The family members are extreme libertarians, who believe in minimal taxation, minimal government aid to the needy, and minimal regulation.

Charles Koch. Photo: Robert Deutsch

Charles Koch. Photo: Robert Deutsch The family empire began with an oil refinery firm founded by Fred Koch in Wichita, Kansas in the 1940s, and its conservative political activism accompanied the business from the start. In the 50s Fred Koch joined an ultra-conservative organization that among other things accused President Dwight Eisenhower of being a communist agent. Koch idolized Benito Mussolini and published an essay stating that “The colored man looms large in the Communist plan to take over America.” Two of Fred’s sons, Charles and David, took over the reins of the company and transformed it into a giant conglomerate. David passed away a year ago and his brother Charles now oversees the vast array of the family’s holdings with his son Chase developing the innovation side of things.

Over the past 20 years, the Kochs have stood out as the driving force behind the Republican Party: they spent millions of dollars on aggressive attacks against Democratic candidates and are among those responsible for the extremist tendencies of congressional representatives that forced moderates to shift further conservative in order to hold on to their seats. The family fought vigorously against legislation attempts by President Barack Obama and in 2012 they donated an astounding $86 million to try to prevent his reelection. In 2018 they launched the Koch Network, an organization of 500 American businesspeople who each pay $100,000 a year to advance conservative causes. The network is considered to be one of the most influential political forces in the U.S., a sort of shadow government with branches across the country that has spent an estimated $400 million to advance its causes over the past two years.

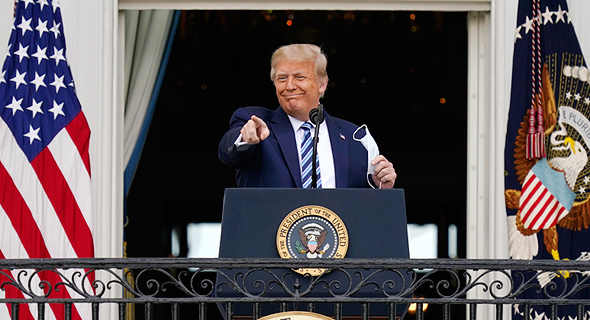

The family itself decided to lower its profile since Donald Trump was elected president. Charles said that choosing between him and Hilary Clinton was akin to choosing between a heart attack and cancer. The family is not fond of the trade war Trump launched against China, nor of his policy of deporting family members of illegal immigrants born in the U.S. All that didn’t prevent the appointment of senior Koch executives to central roles in the Trump administration, nor did it curb the efforts to try to repeal Obamacare. Nowadays, the family is offering support for the appointment of conservative judge Amy Coney Barret to replace Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg on the Supreme Court.

U.S. President Donald Trump. Photo: AP

U.S. President Donald Trump. Photo: AP Groner’s connection to the Koch family was mediated by Eugene Kandel, who currently heads Start-Up Nation Central, an organization dedicated to forming links between Israeli companies and international investors, and during Groner’s time in public service, was the chairman of the PMO’s National Economic Council. Sharing a similar economic worldview, the two remained close. Kandel made the connection with the Koch family and invited them to get to know the Israeli ecosystem better after they had already invested in Insightec.

Many businesspeople and surely tech executives must have issues with their ultra-conservative views

“There are a lot of misconceptions about them. What motivates the Koch family is advancing human society to a higher level. They always operate according to their values, not everyone needs to agree with those values, but that’s what drives them.”

How did you come to work for them?

“I first met Chase shortly after I left the Prime Minister’s Office. He was here on a junket to learn more about the region. We sat together for an hour and a half talking about everything apart from technology, we really connected and kept in touch. He was interested in the work I did on reducing regulation during my time at the Prime Minister’s Office. We also spoke about the natural gas drilling arrangement and I told him about the populist backlash that accompanied it. I was gushing because finally someone was taking an interest in it. I discovered a person with whose values I could identify.”

Values that are considered extreme

“I wouldn’t define them as extreme. He is motivated by the values of liberty and self-realization. These are not controversial values and when you explain that to people, most would agree with them.”

Were the Koch family looking for someone with links to the seats of power?

“No. I was not asked to make contact with the government and we invest in things that have nothing to do with it.”

Are you still in touch with Prime Minister Netanyahu?

“How is that relevant now? I have ties to politicians and senior officials, but only on the personal level.”

You come from the world of finance, not tech and startups. How do you know how to choose what to invest in?

“We have an investment committee and like many other investors around the world, I bring in external experts to examine companies. It’s important to recall that I was heavily involved in tech as director-general of the Prime Minister's Office. I invested a lot of my time in assessing Israel’s technological capabilities and threats. I had to study those issues in great detail, partially as the prime minister’s representative in forming the national budget and the defense budget as part of that.”

So you are one of the only people in Israel who knows what’s in the ‘black box’ that is the defense budget?

“Yes, and I believe that Israel’s defense budget must be high, in part because unlike other budgets, we receive not only security returns on it but also financial returns. After a few years, these technologies seep out into the world. We wouldn't be the cyber superpower that we are if we hadn’t invested in the field within the defense sector. Our superiority in the telecom field in the 1990s was also derived from the defense sector.”

“The Beauty Of The Tech Economy Is That The Government Doesn’t Interfere In It”

Gruner is a rightist, not just in the Israeli sense— he does live with his wife and five children in the West Bank settlement of Elazar (“you’d be surprised, there are a lot of techies in the local co-working space”)—but in the classic right-wing conservative sense, the sort that is rarely seen in Israel. And like his libertarian bosses, he too gets an allergic reaction from hearing about state intervention in the private sector: “Governments are less efficient with resources and capital than private individuals are and that’s why it's better that responsible individuals handle them and not governments,” he says. “That’s also why I chose tech, it’s the most interesting and successful sector of the Israeli economy and is also where there is the least amount of government intervention.”

But then along comes the Covid-19 crisis and suddenly everyone wants the government to help them and pour out funds. How do you reconcile that?

“The government should only deal with matters that citizens and companies can’t overcome themselves."

Was it a mistake to shut down the private sector?

“Of course it’s a mistake to shut down the economy. At Koch Industries we emphasize what we call the scientific process and try to base our decisions on it. Koch was founded by engineers and that’s why we do everything according to scientific or rational considerations. Personally, I haven’t seen any science that supports a lockdown, though I did see science claiming that lockdowns harm the economy. What’s interesting from a scientific point of view is that countries treated the pandemic differently are paying a different economic cost. It will be interesting, after the dust settles, to see which country’s treatment was better.”

How do you reconcile the crumbling economy with the tech boost that we’ve witnessed since the start of the Covid-19 crisis?

“Israeli tech focuses on services that need to compete on the international stage. When you’re trying to sell your products in the U.S., Europe, and Asia, favoritism doesn’t apply, only competition between products and services count and that fosters excellence. That is why I believe capitalism is of the highest value— because only the best win.”

How do you ensure that all Israelis can benefit from the fruits of the tech success, without creating two separate economies and huge income disparities between segments of the population?

“The beauty of the tech economy is that it is purely merit-based and that’s why it’s successful. The more interference there is from all sorts of individuals who are convinced they are remedying distortions, the more distortions they create. The beauty of the tech economy is that the government is not involved in it and that is how things should remain.”

So, you’re saying that the tech sector will save the Israeli economy?

“Someone will have to and I have no doubt it will be the tech sector.”

The Constant Outsider

If there is a single thread that characterizes Groner’s path from childhood to the present, it is being an outsider. He was always the ‘odd man out’ who managed to be accepted into new territories and thrive in them based on merit. He grew up in a small town in upstate New York, where his father was a community rabbi, and when he was 15 the family immigrated to Israel and settled in Jerusalem. Groner was sent to the Or Etzion Yeshiva outside the city of Ashkelon after being rejected from the national-religious schools in Jerusalem for not speaking Hebrew. “My first year at Or Etzion was super difficult. I didn’t speak the language. What saved me was basketball. I still have friends from my time there,” he recalls. After Yeshiva, Groner joined the first cohort of the Bnei David pre-military academy in Eli, an institution that has often made headlines due to racist, homophobic, and misogynist statements uttered by its leaders. “I know it is controversial,” he anticipates the questions, “but when we grew up in the U.S., it was clear that there was the world of the mundane and the world of the sacred and at Eii I first realized that upholding the Jewish state under Israeli sovereignty was sacred. So is serving in the military and strengthening the economy and the courts. Our right to exist rests on Jewish statehood and even though I was raised on the separation of state and religion, that doesn’t apply to Israel, which was only established by virtue of the Jewish faith.”

Eli Groner in his role as director-general of the Prime Minister's Office. Photo: GPO

Eli Groner in his role as director-general of the Prime Minister's Office. Photo: GPO In 1989, Groner enlisted in the IDF’s Paratrooper’s unit and went on to officer’s training, where he excelled. After his discharge, he began studying communications and political science at Bar Ilan University but got bored. “Friends and cousins who stayed behind in the U.S. told me about their internships in government institutes and it bugged me that there wasn’t a similar culture in Israel,” he recalls. “I approached Hagai Elias, who was at the time Jerusalem Mayor Ehud Olmert’s spokesperson and offered to set up a liaison network for foreign journalists. They didn’t know what to make of me, but they let me do my thing.”

From there, Groner went on to become a financial reporter at the Jerusalem Post, where he stuck around for four years. “I quickly realized that it is more interesting to manage the economy than to write about it, so I went to get an MBA at NYU.” In 2002, he started working at Lehman Brothers and a year later he moved to the McKinsey & Co consulting firm, where he quickly became the New York office’s rising star. Groner was a husband and father of two by then and he had promised his wife they would return to Israel after four years in the U.S. so they came back and Groner landed in McKinsey’s Israel office.

As part of his job at McKinsey, he handled the “Tnuva Project,” which later became notorious for recommending to the Israeli dairy company’s controlling shareholders Apax Partners to raise the price of cottage cheese, which sparked widespread demonstrations protesting high living costs in 2011. “It should come as no surprise when a private investment fund behaves as private funds all over the world do. She is committed to her investors and ROI,” Groner says in defense of his former boss, Zehavit Cohen, who was managing partner of Apax Partners Israel. But he is quick to explain that “I was only involved in the operational side of the project, not its pricing and I was pulled off the project in favor of a Defense Ministry project, pretty quickly.” In 2009, Cohen brought Groner into Tnuva and appointed him as her special advisor shortly after Apax bought the company—an acquisition that would be the subject of public outcry five years later when Apax sold Tnuva to a Chinese conglomerate.

After two years at Tnuva, Groner decided to transition to public service and return to the U.S.: “I was 40 years old and one day I saw an ad in the paper that the government was looking for an economic attache in Washington D.C. I decided to apply even though the rest of the candidates were from within the system and I knew my chances were slim. The head of the selection committee was then Finance Ministry Director-General Haim Shani, who was actually very much in favor of recruiting an outsider for the role.”

Groner spent three years in Washington, “and that’s where I first got noticed by Netanyahu after I was able to exempt Israel from an across-the-board cut to the military aid budget,” he recalls. “A short time after returning from Washington the PMO Director-General at the time Harel Locker resigned and as soon as I heard the job was vacant, I rushed to set up a meeting with Netanyahu, even though I had never met him personally.”

How does one initiate a meeting with the prime minister?

“I was after all an economic attache. We met and connected very well, especially when it came to what was needed to be done for the economy, like the establishment of a cyber directorate and developing the energy market.” It worked in Groner’s favor that during his time at McKinsey, he was a partner on the team that produced an outline for reforming the defense budget. “Near the end of the interview with Netanyahu, he told me ‘I think you can be a great director-general, but an essential part of the role is working opposite the finance ministry on the national budget and particularly the defense budget. What do you know about that?’ For me, it was a slam dunk opportunity.”

What about Sara (Netanyahu, the prime minister’s wife)? Did you require her approval for the appointment?

Groner sits silently for a long time before answering with a single word: “No.”

Eli Groner in conversation with Benjamin Netanyahu. Photo: GPO

Eli Groner in conversation with Benjamin Netanyahu. Photo: GPO Groner accomplished quite a lot during his intense term at the Prime Minister’s Office: the so-called Numerator Law, which for the first time forces government ministries to meet measurable goals and outline income sources for every planned expenditure; the establishment of the National Cyber Directorate; a business licensing reform; and of course, the natural gas arrangement. And despite all that he describes his time there as “39 months,” a figure that may hint at how much he enjoyed the job.

Media reports said he left the job under orders of the prime minister’s wife, who turned him into a persona non grata after he refused to approve funding for the renovation of the Netanyahu family’s private home in Caesarea. Now, after a long pause and a careful selection of his words he told Calcalist that he left the job because “I felt that I ceased being effective. The work is never done, but I had stopped being effective.”

Where do you feel that you were being effective?

“It is hard to point to a single accomplishment because there were many, but the development of the Leviathan natural gas deposit was one of the standout achievements,” Groner says, referring to what is to this day still a controversial natural gas outline. “Even before entering the role, I realized that transforming Israel into an energy superpower was a mission of the highest order. Any objective person realizes that and that’s why it was so frustrating to me that five years after discovering the largest reserve of its kind in the Middle East, zero progress had been made due to squabbles over who would benefit and how much. To this day it saddens me that an issue like that, which should receive across-the-board approval, became politicized and controversial. There were many distortions of the truth and it delayed carrying out the right move.”

The thing that was supposed to put the issue to rest was the establishment of the National Wealth Fund, which according to initial plans was supposed to have hundreds of millions of shekels in natural gas royalties sitting in it by now. However, not only is the fund empty, it is in deficit because of the expenses to establish it.

Protesters in 2016 claim the gas companies are robbing the people

Protesters in 2016 claim the gas companies are robbing the people “Everything is going according to schedule. The outline determined that the companies must first return their investments. They invested $4 billion in developing infrastructures and it takes a long time to make that back,” Groner said.

At the time Groner was a vocal opponent of the Sheshinski Law because he estimated that the high fees placed on the gas companies would prevent the royalties from reaching the National Wealth Fund. “The gas was there for millions of years, the state tried without success to locate it and then handed out licenses with clear profit-sharing definitions and, what a wonder— a private company was able to find it,” he said.

A person close to Groner said that “Eli wanted to give lawmakers proper tools to oversee the government’s actions, deriving from the realization that the Knesset (Israeli parliament) had stopped functioning and had descended to populist legislation, losing its oversight capabilities. But he was hated in the government offices because of the Numerator reform and some officials refused to cooperate with him. He would have stayed on to complete the move, but at one stage every day and every hour at the Prime Minister’s Office became insufferable. It was a result of the shift in Netanyahu’s attitude following the 2015 elections — Netanyahu veered away from everything Eli appreciated about him, from being a finance minister who lionized the private sector, he became a person constantly entrenched in private complications and obsessive battles with the media and the legal establishment.”

In 2018 Groner resigned and returned to the business world to run KDT.

Zehavit Cohen, Benjamin Netanyahu, and now Charles Koch. They are all people who have caused masses of citizens to take to the streets in protest against them. How is it that you keep finding yourself working for such controversial people?

“I like people who want to leave a mark on society and humankind. Apparently, only those who do nothing are not controversial.

Do you see yourself returning for another round in politics?

“I am very committed to Koch.”

And if you are called to the flag?

“There aren’t many attractive positions in the public service left for me.”

Not even prime minister?

“I am currently committed to building the platform for Koch.”