Opinion

Hyperloop is not only radical in its technology, but also in its intellectual property strategy

Ultimately, the goal is to merge the hyperloop system with an autonomous uber system, seamlessly connecting a human-free transportation system

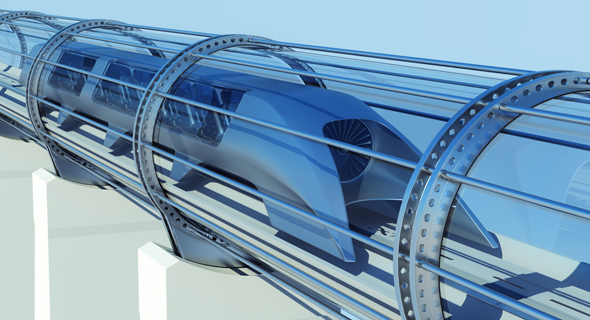

Elon Musk's vomit comet, now known as Virgin Hyperloop, is based on an idea developed more than a century ago by famed rocket scientist Robert Goddard. Essentially, the Hyperloop --its most recent iteration conceived of by Musk and Sherwin Pishevar while on a humanitarian trip down to Cuba-- is a system of reduced pressure tubes that use electromagnets to propel cylindrical pods containing people or freight at exceedingly high speeds between two points. The company just successfully completed a half kilometer trip with passengers at 172 km/h, less than half of its current top speed of 386 km/h, at their test track in Nevada.

The radical technology has caught the interest of many and various Hyperloop routes have been proposed including one in Israel between Eilat and Tel Aviv. But Hyperloop is not only radical in its technology, but also in its intellectual property strategy: much of the early technical ideas were made open source. Supposedly, Musk, lacking the bandwidth to devote to the hyperloop project, although he still has enough to follow through on crazy ideas like a commercially available flamethrower, or more recently, overpriced tequila, reportedly refrained, at least initially, from seeking out patents so that others could take advantage of his ideas. Musk's whitepaper outlining his plan was made freely available online.

The hyperloop. Photo Shutterstock

The hyperloop. Photo Shutterstock Their use, or lack thereof, of IP is not the only legally interesting aspect of the venture. The Hyperloop concept also presents fascinating regulatory questions as it is neither a railway per se, with all its inherent laws and regulations, nor does it fit well with any other current forms of long-distance transportation, such as planes or automobiles. Notably, at least in the U.S., many issues that come up in this novel area can be dealt with by the Non-Traditional and Emerging Transportation Technology (NETT) Council of the Department of Transportation.

However, Hyperloop not willing to sit back and wait for the U.S. government to iron out the regulatory issues has taken a more aggressive tack in its effort to deal with the potential governing mess. They reached out to countries around the world that were both interested in building their own Hyperloop and were also willing to work with the company to develop the optimal regulatory environment to make that happen.

Hyperloop is not the first technology company to help create its own regulatory environment. Other innovative technologies have also attempted to guide their own regulatory development, for better or for worse, including in the areas of privacy, fintech, drone deliveries, space tourism, and autonomous vehicles.

It remains to be seen how the law will practically regulate Hyperloop. And while many have already written it off as a failed experiment, we hope that this recent test will revitalize industry interest in the model as well as create novel regulation for similar projects.

Notably, that fateful flight to Cuba was not Pishevar’s only Caribbean interest. In October, presidential hopeful Kanye West announced that he is working with Pishevar in Haiti to develop a smart city on the Tortuga/Turtle island, to the understandable consternation of many Hattians.

However, while the Haiti effort did not get that much coverage internationally, Sherwin Pishevar’s more famous investment, Uber, has. Uber's recent local success in California may have broader repercussions, albeit at the expense of its drivers, which arguably, Uber intends to ultimately replace with robots anyway.

Pishervar’s Uber was a big part of a state-based campaign this election season that could have consequences across the country, and perhaps beyond. California is somewhat of a direct democracy in that the population often votes on various proposals directly, circumventing their legislature and even the courts, with mixed results.

In September 2019, the California Legislature passed Assembly Bill 5 (AB 5 aka The "Gig Worker law") codifying an earlier California Supreme Court ruling that would have ultimately made many gig economy workers into employees, rather than independent contractors.

AB 5 had pros and cons for both the industry and the former contractors; many companies refused to comply. In October 2020, the California appellate court ruled that companies like Uber and Lyft, which had heretofore mostly ignored the law, must treat their drivers as employees and provide the legally required benefits. Those companies --neither of which are yet profitable and would be less likely to be so if they were forced to provide substantial additional capital in their payroll — as well as other gig economy ridesharing and delivery companies — fought this ruling at the ballot box in the form of Proposition 22 via a record-smashing $205 million political campaign.

The ‘yes’ vote on Prop 22, which won by a relatively wide margin, was designed to circumvent AB 5 and the subsequent legal rulings for many, but not all formerly gig workers; cleaning staff and retail employees can still benefit from AB 5, for now.

Under Prop 22, which goes into effect in December, driveshare and delivery workers will be back to being considered independent contractors with significantly fewer benefits than employees. While these workers will still be a bit better off than they were before AB 5, Prop 22 was designed to benefit primarily the large drive sharing and other delivery companies, arguably promising gig workers much less than minimum wage, according to the University of California Berkeley, although a competing University of California, Riverside assessment disputes that finding.

The seeming excessiveness of the proposition underscores much of what is wrong with the direct democracy system in California, which often comes back to bite later generations of voters. For example, Prop 22 goes above and beyond to help these companies, mandating a 7/8s supermajority of the legislature to change the law, something unlikely in the notorious gridlock of California government.

Emboldened by their fresh win in California, Uber and Lyft are now looking to take their efforts nationally. Uber has been especially active in seeking out a federal law to solve this issue once and for all.

And if things couldn’t get worse for Uber and Lyft drivers, Mobileye and Volkswagen aim to have robot taxis on the road in Tel Aviv by 2022 further eroding their job security.

Ultimately, the goal is to merge the hyperloop system with an autonomous uber system, seamlessly connecting a human-free transportation system. Maybe Tortuga, where Columbus first set foot in 1492, is a good place as any to start fresh.

Prof. Dov Greenbaum is the director of the Zvi Meitar Institute for Legal Implications of Emerging Technologies at the Harry Radzyner Law School, at IDC Herzliya