Interview

“SpaceX brought that Silicon Valley, entrepreneurial corporate culture to space,” says astronaut

Former NASA astronaut Garrett Reisman speaks of his career at Elon Musk’s SpaceX and how it’s defying the status quo, the hottest space tech companies for investors, as well as his time spent floating above the majestic vastness of the Earth

Garrett Reisman (52) is a former NASA astronaut, a professor of Astronautics Practice at the University of Southern California's Viterbi School of Engineering, a former Director of Crew Operations at SpaceX, and an admirer and supporter of the Israeli space scene. He holds a bachelor’s degree in mechanical engineering and applied mechanics from the University of Pennsylvania, as well as a master’s and PhD in mechanical engineering from the California Institute of Technology. He spoke to CTech about his time spent conducting spacewalks in the International Space Station, his career at SpaceX and how it is revolutionizing the private sector, as well as the advantages that Israel has in that regard.

Former NASA astronaut Garrett Reisman. Photo: Shutterstock/NASA

Former NASA astronaut Garrett Reisman. Photo: Shutterstock/NASA What were your impressions from Israeli Space Week?

“I’ve gone to many Israeli Space Weeks, and am impressed by how the Ramon Foundation is carrying on Ilan’s mission. Obviously the pain of losing him is indescribable, but it’s also the loss of the entire country, and he inspired the next generation to pursue space too,” Reisman told CTech’s Yafit Ovadia, after participating in the Ramon Foundation's Spacetech Conference during Israeli Space Week.

“Although there’s plenty of sadness, seeing the smiles on childrens’ faces and all the quality work done here is really uplifting and is the silver lining to the story. Everyone did a great job of pulling it off, and all the conferences, contests, and panels took off, even if they were all done virtually.”

What are your hopes for the Israeli space sector, and how do you expect it to grow?

“As far as technology goes, Israel has always been a leader. Since the country's founding, that tradition of science and discovery is there. Given the current challenges, I think Israel will shine through its peaceful uses of technology, which has become a part of its national character, and goes hand in hand with space exploration. There are lots of niches where Israeli technology can contribute to things as grandiose as the human exploration of our Solar System.”

How did you transition from the public sector to the private sector?

“When I first visited SpaceX’s launchpad in Florida, I was really impressed with how innovative they were, and how quickly they were getting stuff done, and how efficiently. They were getting things done in months, which would take NASA years,” he said.

“That’s when I had this sort of Eureka moment that there might be something to this.” He recalled how former astronaut and VP of SpaceX at the time Ken Bowersox gave him an extensive tour of their factory in Hawthorne, California. “I was hooked. I saw the potential, even though at the time it was just starting. I met with Elon Musk, and he interviewed me. I voluntarily stopped being an astronaut which was a very difficult thing to decide to do, but I wanted to be a part of this.”

At SpaceX, he served in a variety of managerial positions, including as director of crew operations where he oversaw commercial crews projects. He also served as director of proposal teams, which would compete with other commercial entities for large government contracts, and won the heftiest one for $2.6 billion, worked as a senior engineer on astronaut safety and mission assurance, and lastly as a consultant.

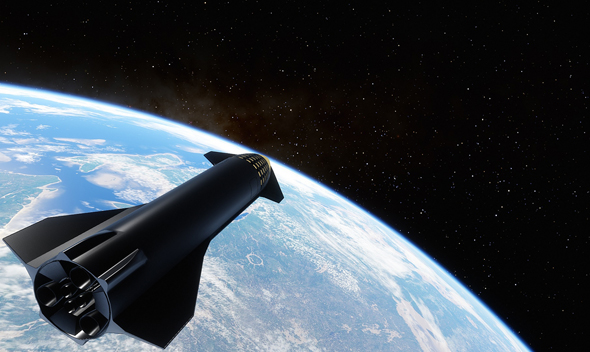

An illustration of SpaceX's Starship rocket which is still in development. Photo: Shutterstock/SpaceX

An illustration of SpaceX's Starship rocket which is still in development. Photo: Shutterstock/SpaceX

How is innovation at SpaceX different than at other space tech startups?

“SpaceX really led the way. Now, you have a lot of other companies trying to do the same thing, and follow in their footsteps, like Firefly Aerospace, Relativity Space, even Virgin Orbit. SpaceX was really the first. There were attempts, but no real successful ones prior to SpaceX.

“SpaceX really brought that whole Silicon Valley, entrepreneurial culture to an industry that had a very different corporate culture. That was revolutionary. There were a lot of things that were very different in how SpaceX went about their work compared to how NASA and other traditional aerospace companies do. What was particularly striking was the quick speed in which decisions were made. We’d make decisions in a single meeting or even weeks or maybe months, something that would take years to do in a traditional setting.”

Meaning compared to NASA, since it’s a government run agency, where things run a little bit slower?

“Yes, but even in the private industry, for companies such as Boeing, Lockheed Martin, or Raytheon, decisions are made at a much slower pace. At SpaceX the entire concept was to make a decision and move forward, so that if we’re heading in the wrong direction we’d find out quickly. The fastest way to discover how to do something is to try something today, rather than think about it for a year. That sounds obvious, but the reason why it’s not commonly done by these big companies is because the pain of making a change is so high.”

“The problem with having such a quick decision speed is the possibility that if you make a wrong decision, it can be disastrous if the consequences are particularly high. SpaceX enjoys a tremendous amount of agility - something that other parties lack - so if you made the wrong decision you could quickly learn from that mistake and turn it around. Yet, that’s not something you can do when you have a prime contract like Boeing does with thousands of subcontractors, suppliers, and supply chains who don’t have that kind of agility. You have to get it right the first time. That’s why those corporations move relatively slowly.”

So the corporate culture at SpaceX is just to go forward with ideas even if they lead to failure? You don’t just have a bunch of smart people in one room, you have a lot of risk takers essentially.

“Exactly. But you’re also creating opportunities where the consequences of failure are low, and thus you can really embrace failure. That failure isn’t only tolerated, it's encouraged. Build something, test it, learn your mistakes, don’t be afraid if it fails,” he said. Reisman contrasted it with how NASA tested its rocket, the Space Launch System (SLS), which had spent some ten years in development and which it aimed to have fully operational by the following year. After it failed, the teams were crushed, because they had not originally planned on making major changes to the design since they were already intending to use that very same rocket a year later. Something that wouldn’t happen at SpaceX.

“It was a ‘validation test’ - you expect it to work, and it has to, because if it doesn’t then it messes up your schedule. SpaceX will often do a big test like that with the expectation of failure,” and recalled the flop of the Starship Serial No. 8 craft a month ago, which left a gaping crater in the ground upon its explosion, and explained how SpaceX considered that a massive success. Now, SpaceX has already made improvements to that vehicle, and has gone forth launching its Serial No. 9 just this Wednesday.

“That’s a really good example of two ways of doing things - the public and private sector - and how they’re so different,” he said.

What are some of the space tech startups that are hot right now that you’d recommend others consider investing in?

“Despite what people may think, a lot of investments are flowing into the space sector, such as in the fields of satellite designs for consumer telecommunications, or nanosatellites or constellations of satellites that can provide different remote sensing capabilities,” he said, “some are interested in looking at crop yields for agritech, others are looking to predict how successful a company is by having satellite data on how many cars are in their parking lot. There’s all kinds of things you can do with data that you obtain from space, as long as the cost of access to space is low. If so, there’s all kinds of business applications that you would never consider in the past. If the satellite and rockets are cheap then all these things will become possible too.”

He also recalled SpaceX’s ambitious Starlink program which aims to connect entire countries to broadband networks.

“In the U.S. at least, a lot of venture capitalists are putting money in small launchers, like SpaceX did, which didn’t start with the successful Falcon 9 rocket contrary to popular belief, it started with the Falcon 1 that you could essentially tow behind a pickup truck. SpaceX started small and then scaled up to later models. Some companies who are doing this include Firefly Aerospace, Planet Lab, Relativity Space, and Virgin Galactic who successfully put their first payload in orbit. Virgin also has a suborbital division which is designed for suborbital space tourism. You can buy a ticket today and go on a ride that takes you right to space, although it’s still in development. It takes you straight up and straight down, but it’s a short flight - some 15 minutes - and it’s not like (second-Israeli astronaut) Eytan’s flight,” he quipped. “You don’t get to stay very long.”

Their headquarters are based out of New Mexico, where they have the first space port, similar to an airport in many ways.

“There’s also Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos’ Blue Origin which is based out of West Texas, and has designed the New Shepard rocket and is doing the same thing. There’s also Virgin Orbit that has a modified Boeing 747 plane that can carry a small rocket to altitude and drop it in space, and can deploy small satellites into orbit.”

He noted how Amazon is also working on the Kuiper Project - named after the Kuiper Belt of asteroids on the far reaches of the Solar System floating past Neptune - of lightweight antennas that customers can use for satellites that provide broadband internet coverage from space.

A launch of SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket which is used to deploy satellites into space. Photo: Shutterstock/SpaceX

A launch of SpaceX's Falcon 9 rocket which is used to deploy satellites into space. Photo: Shutterstock/SpaceX

In your current position as professor of astronautics practice at USC, what are some of the courses that you teach? How can students apply this material to their lives even if they don’t necessarily go on to become astronauts?

“The courses I teach are for graduate students in the field of engineering, and all relate to human spaceflight. I realized when I was at SpaceX that there are some areas where we can hire people straight out of college, for writing computer code or doing structural analysis, but if you need someone to construct a space suit or to figure out how to operate a spacecraft, or mission planning - they don’t teach that in college. We try to teach all that on the job, but I thought it’d be better to know what all these things mean on day one. You can get a job doing these things today. While the course is purely academic, there are definitely practical applications to this subject. Many students can later use this material to go on and become flight engineers - even if they don’t necessarily become astronauts. That’s something that I found was lacking in the space tech industry. We have plenty of smart people, but we need to train them. We’ll be better preparing students to enter the workforce by establishing a pipeline from academia directly to the industry.”

What is your position on incorporating more women into the aerospace and aeronautics industry?

“There aren’t many women or minorities in these fields, it’s not only a moral problem, but is an ethical problem as well. I serve on a faculty committee at USC that is working to improve our minority representation, and incorporating more women as well into these types of fields. Gender and race have unequally been represented in science and engineering in general, especially in the space sector. From a practical standpoint, it’s stupid. They clearly make up a significant amount of the population, but are held back in many ways. Somehow, we’ve managed to put a man on the Moon while working with only a fraction of the population. We would have a city on Mars by now if everybody who could contribute was free to do so.”

What were some of the things you accomplished as an astronaut?

“I launched in 2008 and in 2010, both times to the International Space Station, and conducted routine work onboard when we were still building the station. In 2008, I was the first Jewish crew member aboard the station and it was an honor, and a certain distinction,” he added.

“Greg Chamitoff came after me, and he was the second Jewish astronaut aboard the ISS. Hopefully, there will be even more in coming years. Now things aboard the station have changed, the crew there is constantly busy conducting experiments and there’s so much data to analyze. They’re really fully utilizing the station.”

“I conducted three spacewalks, and we installed three new modules and new equipment, and spent a lot of time troubleshooting and getting stuff running. Perhaps one of the most significant experiences in my life, and in space was conducting spacewalks. It was crazy. It was the most visceral life experience of the whole mission of traveling in space. The first time you got out there, it’s quite overwhelming,” he noted. “It’s a combination of the familiar and the outlandish. All your tools are familiar from the simulations, all the cables and bolts are right where they’re meant to be, and yet you look up and you suddenly see the entire East Coast fly by. It’s strange. On one hand, you’re floating out there in space, you’re doing a job and have a lot of pressure to accomplish those objectives. This is probably the most important job you’ll ever have in your entire life and you don’t want anything to go wrong and must remain focused, and yet at the same time you’re being ridiculously distracted by the most insane sensory experience you’ll ever have in your life.”

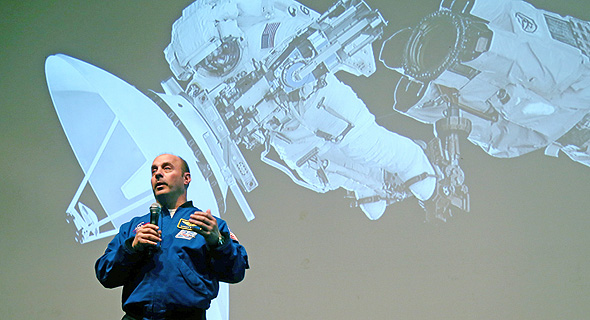

Reisman speaks to an audience during Israeli Space Week in 2017 about his experiences conducting spacewalks. Photo: Yariv Katz

Reisman speaks to an audience during Israeli Space Week in 2017 about his experiences conducting spacewalks. Photo: Yariv Katz How do you think the sector is changing to incorporate private astronauts and how will that alter the future of space exploration or human spaceflight?

“We’re at a real inflection point, or a real seat change. It was actually the Russians that started it with their Soyuz capsules. I’d say this is the first time in the Western World that we’re really getting the ball rolling with allowing private citizens to get access to space. While NASA always worked with private companies, they’ve decided to engage the private sector in a whole new way - by having more contracts and agreements with companies like SpaceX to speed up development. I think that the relationship between both government and private contractors, in material support and operations is all changing, for the better. We’ll definitely see more private astronauts, and it’s exciting.”

How do you think people every day can find importance and value from looking up at the stars? What message do you believe your missions send to the general public?

“I would start with the famous photo that Bill Anders took on the surface of the Moon during the Apollo 8 mission of the Earth rising amid space. Just realizing how fragile our planet is, how fragile the atmosphere is, should make us appreciate and strive to better care for our planet. And yet, this can go one of two ways - either, in a depressing turn of events, our planet will be wreaked by destruction, wars, and desolation if we don’t strive to protect the environment. On the other path, which is more positive, I hope that we can protect the Earth, and put aside our differences to discover other planets - something that will teach us that our planet is special and there’s none other like it.”