Analysis

Israel is lagging behind the rest of the world when it comes to e-commerce regulations

The Ministry of Justice has started formalizing the relations between Israeli consumers and foreign e-commerce sites, with the big question being will Israeli laws protect them?

20:4324.02.21

If there’s one thing that the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic significantly changed, it’s e-commerce. Popular even prior to the pandemic, the field marked a significant jump due to the widespread and continuous closures that prevented people from shopping in stores or malls, which led many Israelis to increase their online purchases. Quite a few local websites benefited from the transition, but it was even more marked in traffic to large overseas e-commerce sites, such as Amazon, Next, eBay, and AliExpress.

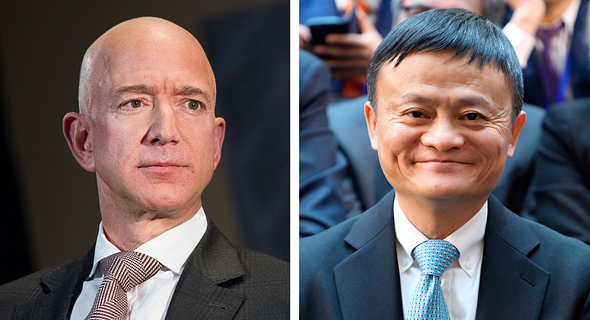

Alibaba CEO Jack Ma (on right) and Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. Photo: AFP/AP

Alibaba CEO Jack Ma (on right) and Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. Photo: AFP/AP

The Israeli Ministry of Justice has only now begun to embark on a series of proceedings that will examine and re-define the relationship between the Israeli consumer and international e-commerce sites, mainly in an attempt to answer an essential question: in the event of a dispute between sides, will the Israeli courts or the courts of the country in which the companies reside be the ones to determine Israeli consumer regulations? This isn’t a trivial question, and its answer has possible ramifications as to the power that Israeli consumers wield in the relationship.

Alibaba CEO Jack Ma (on right) and Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. Photo: AFP/AP

Alibaba CEO Jack Ma (on right) and Amazon CEO Jeff Bezos. Photo: AFP/AP Providing legal consent without knowing the details

Nowadays, when an Israeli consumer makes a purchase on an international site, oftentimes he or she agrees during the registration or purchase process to terms and conditions that signify legal consent that in the event of a dispute, jurisdiction falls on the country where the site is located in (usually whatever country the site operates in, or where the law favors the seller, and occasionally even contradicts Israeli law).

Many consumers are unaware of the existence of these conditions. “Communication between parties is done through a uniform contract, whereby the customer agrees to the conditions of the contract that the retailer provides by clicking ‘Yes, I agree,’ but without negotiating those conditions, or giving the customer a chance to receive additional explicit explanations,” reads one document that was published by the Ministry of Justice. “Occasionally, the customer clicks on ‘I agree,’ without even having read the contract.”

Even in cases where the customer is aware of the clause, the consumer has no real choice but to agree to the terms if they wish to make a purchase. “The Israeli consumer who wishes to complete a purchase cannot do so without agreeing to the terms of the contract, although they may not be familiar with the law that the contract refers to, or doesn’t understand the meaning behind the foreign law.”

The result, in most cases, is that when a dispute arises and the Israeli consumer decides to bring forth a lawsuit in court, the Israeli court is forced to decide ahead of time whether it holds the jurisdiction to rule, or whether it must forward the case to the country cited in the contract. In several lawsuits which were recently brought forward against companies such as Facebook, Google, or Twitter, the question arose in early stages of proceedings, when the defendant company sought for the lawsuit to be rejected out of hand.

In a few prominent cases, the court ruled in favor of the plaintiff and decided that the lawsuit would be conducted in Israel. However, the Ministry of Justice noted, “there aren’t always clear answers in Israeli legislation or precedent and occasionally there is uncertainty, and the law is ruled on a case by case basis.” Either way, the litigation places an obstacle before Israeli citizens who wish to sue a foreign platform in Israel, makes it difficult for a lawsuit to be conducted locally, and significantly prolongs the entire process.

A prominent example would be the lawsuit brought forth by Israeli journalist Linnoy Bar-Gefen against Twitter, as a result of profane sexual harassment tweets made against her which the social media network delayed taking down (and only removed after being contacted by her lawyer). The trial itself has yet to begin, and the initial hearings were over Twitter’s demands to conduct the lawsuit overseas. Twitter even brought forth a lawsuit that featured extreme defamation against Bar-Gefen, so much so that Israeli Magistrate Court Judge Gilad Hess was forced to reprimand the company and demand it pay her NIS 20,000 ($6,000) in damages. Though Hess denied Twitter’s request, the issue is ongoing since the social media giant appealed his decision on Jan. 20, 2021. The saga isn’t over yet, as Twitter will still be able to appeal to the Supreme Court - all over the question of whether the legal proceedings needed to be conducted in Israel or not, without the court even pausing to address the essence of those charges.

A partial arrangement

The issue holds significant weight and legislation to regulate it would remove a major stumbling block preventing Israelis from filing lawsuits, and will greatly empower the Israeli consumer opposite international companies. Despite this, the Justice Ministry is limiting its move to address the relationship between internet users and e-commerce sites. “Online transactions are regarded as transactions that justify providing extended protection to users, since the power and knowledge discrepancies between the consumers and multinational businesses are especially large,” the ministry explained. “In those transactions, the consumer conducts a virtual transaction with a dealer they are unfamiliar with. The consumers can’t see the product, or assess it, and they aren’t dealing with a human entity that can provide answers to their questions. Occasionally they are also overloaded with information which can significantly harm their decision-making.”

In that regard, the ministry notes that its move won’t bet precedent-setting. “There are types of transactions where the legal precedent has already ruled on the criteria of the law’s application. Recently, section 47 of the Payment Services Law came into effect which applies to payment services providers who are not residents of Israel, yet offers their services to Israeli customers.”

Several other countries have already ruled that local consumer law will assume precedence even in cases where the user agreement states differently. “In Switzerland, parties have been denied the option of choosing which jurisdiction the transaction falls on, and private international law says that the law which applies to consumers will be that of their country of residence. Under European legislation, a consumer cannot be refused essential protection that is provided to them by the rules of their local place of residence,” it read.

The ministry’s move is still in its infancy, and it has issued a call to the public and to relevant bodies to voice their opinion on the matter. The ministry is asking the public to address issues such as whether a uniform contract can supersede Israeli law, whether legislation should be passed to ensure if and when Israeli law can protect Israeli consumers online, and whether such regulations must apply only to individual consumers or also to Israeli businesses. The ministry is also asking to hear the position of foreign providers who service Israeli customers regarding their justification for why Israeli law should or should not apply to them, and what the situation is like in other countries where they operate. The ministry will be gathering the information until March 16.