NFT sells for $69 million ushering in a new era of art history

From a gif of a flying cat to massive auction bids on Christie’s, art on the blockchain is changing the meaning of ownership

Nyan Cat, the Gif that started it all.

Nyan Cat, the Gif that started it all. But hold on a minute, what is an original gif file? How can a file that was created on a computer, can be perfectly duplicated, and has been shared millions of times suddenly be recognized as an original work of art as if it was Leonardo de Vinci’s original Mona Lisa hanging in the Louvre? The answer is blockchain, the technology behind cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, which has revolutionized the art world by allowing for the first time ever for a file of a digital artwork to be marked as an original and coded with the artist’s “signature,” granting it something that digital artists and art collectors have been long yearning for — commercial value.

How does it work? Just like when issuing a new coin, an artist can upload an image file on a blockchain platform and issue it as a Non-Fungible Token (NFT) or a “nifty” which is marked as being one of its kind and nontransferable. The token is essentially a line of code on the blockchain network that includes all the information about the artwork including its creator, and ownership history, akin to an artwork registry listing. The Token can be sold to the highest bidder, usually only in exchange for cryptocurrencies such as Ether.

There are currently 10 primary platforms for the sale of crypto art and they usually operate on the ‘drop’ method — an open auction that starts at a predetermined time and ends a short while later. In addition to the sales platforms that charge a commission, the artists also have a clear interest in selling their work on the platforms since unlike in traditional art, NFT sales are conducted through a smart contract which determines that the artists get a royalty payment every time the artwork is subsequently resold.

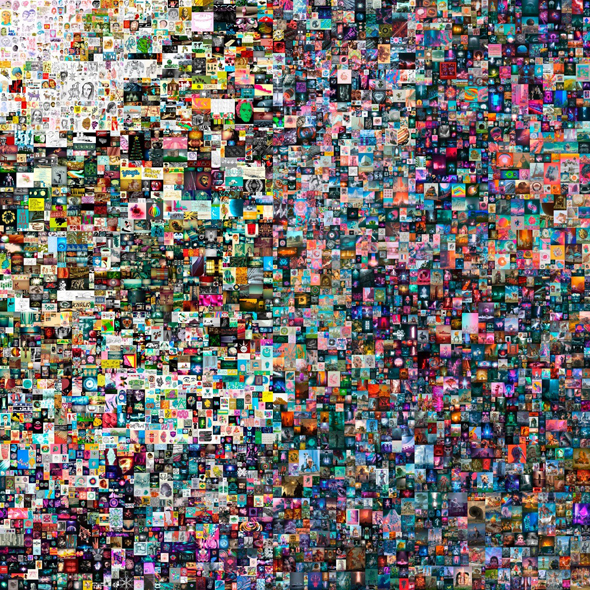

Since its birth roughly four years ago, the crypto art world has experienced a meteoric rise, reaching $250 million in sales in 2020 alone, four times what it made the prior year. Alongside popular Instagram artists, a fair share of celebrities have sold their crypto masterpieces, including tech guru, billionaire Mark Cuban, ‘Rick and Morty’ co-creator Justin Roiland, YouTube sensation Logan Paul, and Linkin Park vocalist Mike Shinoda, who sells parts of his songs as NFTs. On Thursday, art history was made when a digital artwork named ‘EVERYDAYS: THE FIRST 5000 DAYS’ by crypto artist Beeple was sold on auction by Christie’s for a staggering $69,346,250, with the price climbing by $45,000,000 in the final moments of bidding. The sale makes the mild-mannered graphic designer among the top three most valuable living artists and puts his work in the list of the top 50 most expensive paintings ever sold at auction, in the same league as the likes of Vincent Van Gogh, Paul Cezanne, and Pablo Picasso. There are those who believe that crypto art is the biggest revolution to hit the art market in decades and with prices like that they may not be exaggerating.

Everydays, by Beeple was sold in aucton for $69 million

Everydays, by Beeple was sold in aucton for $69 million “The Psychological Question was Whether People Would Feel Like They Even Owned Something”

For digital artists, crypto art is first and foremost the shattering of a particularly thick glass-ceiling. “Most digital artists — 3D artists, animators, digital illustrators, etc… — make their money on commissions for their work,” explains art researcher Danielle Zini. “Before the arrival of ‘nifties’ they generated income mostly from commercial jobs, working in advertising or merchandising like T-shirts depicting their work. But they didn’t have a platform to showcase and sell their artwork.”

They may have been “internet famous,” with millions of followers on Instagram and commercial collaborations with super brands or A-list stars — but were still unable to enter galleries and museums or sell their works to collectors, cause there simply wasn’t any way to do it. And then along came Matt Hall and John Watkinson.

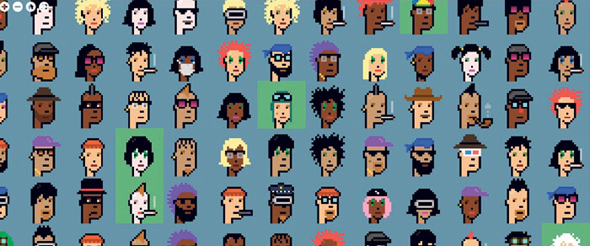

Watkinson and Hall were software engineers and app developers who enjoyed drawing figures in pixel art and decided to jointly establish Larva Labs to give free rein to their artistic tendencies. After they had amassed a respectable number of characters, they decided to find a way to generate income from them. In 2017 they launched the CyberPunks project, during which they sold 10,000 pixel figures, or to be more precise, 10,000 ownership certificates of the figures.

In an interview with Art Market Guru magazine’s le Journal, Hall referred to the project as an experiment of sorts. “The psychological question was whether people would feel like they even owned something under this system. When you have a painting on the wall you feel confident you own a piece of art, it wasn’t clear the same would be true of ownership of digital art recorded on a blockchain.”

Crypto Punks by Matt Hall and John Watkinson

Crypto Punks by Matt Hall and John Watkinson The issue of ownership is a critical one when it comes to digital art: not only do the buyers not have an original piece that they can hang on their living room wall, they don’t even receive a file of the image — the work itself is stored on the crypto platform it was sold on, with only a line of code with a certificate of ownership existing to prove its owner. Even the commercial rights to the piece usually remain in the artist’s possession and not transferred to the buyer. In a sense what changed hands was not the work itself, only the bragging rights for owning it.

The solution that Hall and Watkinson came up with, which has become the standard when it comes to crypto art, is based on the distinction between ownership and possession — you can possess a piece of art, without owning it, just like buying a music album doesn’t make you the owner of the musical number that is recorded on it. In the same way, everyone can keep on sharing gifs of the Nyan Cat without anyone suing them for copyright violations, but only one person in the world is actually identified as its owner.

“Ownership in the digital world is not black and white. There are many shades of grey when it comes to types of ownership over works of art,” Zini explains. “Beeple, for example, allowed fans to download his creations years ago, and we even did VJ sessions with them. Those files are still legally saved in a folder on my computer. However, he is free to auction them off to whoever he wants.”

Despite the complexity of owning crypto artwork, Watkinson and Hall’s experiment was a big success — to date the figures they created in that historic project have raked in $98 million in re-sales, with each one going from around $16,000.

“Finally, the Pursuit of Likes is Paying Off”

Mike Winkelmann (39) looks like your typical guy from the U.S. suburbs. He is married and a father of two who lives in Charleston, South Carolina, works as a graphic designer, and drives a Toyota Corolla. His hair is parted to the side and his wide grin and rectangular glasses lend him the appearance of a young Bill Gates. There's nothing about his appearance that would give away the grotesque and depraved imagery that appears in his artwork, which have transformed him — under his avatar name Beeple — into a rising star in the art world: from a naked Joe Biden urinating on a giant figure of Donald Trump to a line of Michael Jackson-looking androids carrying incubators with fetuses in their abdomens to Homer Simpson wearing a Homelander costume, shooting lasers out of his eyes his son Bart’s head.

"Sweet god I hope this picture stands the test of time", by Beeple

"Sweet god I hope this picture stands the test of time", by Beeple It all started in 2007 when he came across the work of British illustrator Tom Judd, who set himself a task to draw one sketch a day. “I thought it was a cool idea and at the time wanted to improve my illustrations skills, so I decided to go for it and uploaded a new drawing online every day,” Winkelmann told Calcalist prior to Thursday’s massive auction. “Near the end of the year, I realized that I had learned a lot, meaning I was still really bad at it, but I had improved a lot. I wanted to study 3D programming, but knew nothing about it, but had by then figured out that it was a good way to develop self-discipline. From there, things simply happened by themselves, and last January I marked 5,000 days.” Beeple didn’t miss a single day, including the days his children were born, and he is still keeping it up, posting a new drawing or an animated video to his Instagram account (@beeple_crap). In time, he became an Instagram sensation with 1.9 million followers, which earned him enviable collaborations with Louis Vitton, Arian Grande, and Justin Beiber. Despite all that, when it comes to the established art world, Beeple — like many of his fellow artists — has not received his due recognition in terms of exhibits and sales to collectors. Then in October, he discovered the crypto world and nearly overnight became a millionaire.

A representative of Nifty Gateway — considered the heart of the crypto art world — chased after him for weeks asking him to join them, before he finally relinquished. “People had been telling me to check it out, but honestly, I simply didn’t get it. When I finally looked into it seriously, I realized how insane it is. People actually buy these artworks.” Beeple sold three pieces in his very first drop, one of them (Crossroad) for $66,666. “I thought to myself, ‘Woah, what the hell happened here?” he recalls. “I never thought I could sell my work at such substantial sums. In retrospect, those prices are low compared to what those works are worth today.”

Mike Winkelmann, AKA Beeple

Mike Winkelmann, AKA Beeple Beeple’s second drop, which took place in December, is considered a landmark moment in crypto art history — in less than five minutes Beeple’s work was sold for more than $500,000. By the end of the weekend, Beeple had sold 20 of his artworks (some as sole copies and some in multiple copies) for $3.5 million.

“Beeple’s December sale was a turning point that brought a lot of attention and legitimacy to the space,” says Rhett Dashwood, an Australian crypto artist, and art collector, who was fortunate enough to obtain a copy of the “Bull Run” during that historic weekend. “For years digital artists had been working, fostering Instagram followings for exposure and ‘likes,’ now they can finally turn those efforts into a profit. I was in a state of shock at the time of the sale, but I knew it was an amazing moment.”

That sale broke the glass ceiling and brought Christie’s’ representatives to Beeple’s door. “I couldn’t believe it because I had just entered the scene. I may be a popular designer, but I never thought my works would turn into collectibles,” he says.

“Nifties remind me of the early days of the Internet, when we all thought to ourselves, ‘OK, what do we do with this?’ and then realized it had a million different uses. That’s the thing about this technology, art is just one of its use cases. People use it for ticketing, purchasing virtual land in virtual worlds. NFTs on their own only provide proof of ownership and because of that can be used for anything where that’s required. I think we are still only in the early days, but that’s going to change this year,” he said.

“Where Does the Value of Art Rest?”

Irish conceptual artist Kevin Abosch is one of the pioneers of crypto art, but even so he hates to be called a crypto artist. “The technology is nothing but a means to market the art,” he told Calcalist. “If I start selling my works in an alley behind the supermarket, will people call me a back alley artist?”

At 52, Abosch has several decades as a successful portrait photographer behind him, but the hype around him has only picked up in earnest in the last few years. It began in 2016 when he sold a photograph (an actual physical print) of an organic potato to a European businessman for 1.2 million Euros. The attention around the sale and the fact that it was of a photograph — meaning a copy that was sold as something unique— got him thinking deeply about the value of art. Two years later, on Valentine’s Day 2018, he sold to a group of 10 collectors a photo of a rose as an NFT on GIFTO for a sum that was worth one million dollars in crypto.

'Forever Rose, by Kevin Abosch

'Forever Rose, by Kevin Abosch What value is there is owning a piece of digital art that has no physical world representation or even sole ownership?

“Intangible art is a thing that exists and has value. I was speaking to someone a few days ago and he told me ‘I’m not going to pay money for something I can’t see.’ To which I answered, ‘what do you mean? you pay for a subscription on Spotify or Apple Music, that means it holds value to you.’”

The media attention over the price his works had sold for led Abosch to release a series of works in 2018, called “IAMA Coin.” The pretentious idea behind the work, which earned him a profile piece in the New York Times, was to physically link his body to the blockchain. What does that mean? Abosch issued 10 million tokens on the Ethereum blockchain and sold them to collectors. He then drew six vials of blood from his body and used them to print the tokens’ blockchain address on 100 pieces of paper. In this way, he claimed, he was selling “pieces of himself.”

“The really interesting question for me is where does the value of art rest? Is it in its physical manifestation? Maybe it’s in the conversations that you have about it?” Abosch suggests. “Many people — definitely those that grew up in a world of games and virtual assets— wonder ‘why can’t we be the owners of digital assets? Why do they disappear when I lose my account?’ I call it the ‘attention economy,’ with the underlying idea being that attention has value that exists even after it has shifted somewhere else, that it is ‘prima materia’ — the stuff that potentially, the universe is made up of. Does something even exist if nobody pays attention to it?”

$900,000 for a Suspected Banksy Original

“What has been playing out in the crypto art world in recent months feels a little bit like a bubble that is about to explode,” says illustrator and designer Oleg Milstein, one of the pioneers of the Israeli Nifty scene, who recently sold three gifs of pixel figures for $130 per copy on Rarible. “Prices have spiked insanely. For every piece you upload to Rarible, you are required to pay a commission. Prior to the Beeple craze, the fee was four dollars, nowadays it can reach $50 to $70. The problem is that the more new pieces are added, the older ones get pushed down and it’s impossible to get any exposure. Even more problematic is that a lot of platforms are filled with garbage, they have become flooded by works of kids who learned a little photoshop and lack any artistic value. It will take a while for things in the scene to balance out.”

What value can there be to mark a file, which by definition is generic, as an original?

For us artists, there is immense value. Until now, video and animation artists had a difficult time proving ownership of a piece after it started spreading online. Thanks to the technology you can see the entire ownership history of the token, which is also immutable — so much so that if I upload a piece and see that I made a typo, I can’t go back to correct it. It becomes like a physical work, as soon as it’s done, you can’t touch it.”

It feels like the art world is forcing its old rules on a new and radically different medium.

“It’s true that suddenly things like agents, promoters, hierarchy, and chasing after collectors have entered the digital art scene, but unlike in the traditional art world, here, everything is public and transparent, including the sales amounts, which makes things a bit easier. At the end of the day, when the dust settles, the prices will match the quality of the art and we won’t have the craziness we’re experiencing now.”

For now, however, madness rules. Last month a scandal erupted on trading platforms OpenSea and Rarible, when a mysterious user by the name of Pest Supply uploaded artwork inspired by Banksy, and chiefly one called “NFT Morons,” which was a riff on Banksy’s “I Can’t Believe You Morons Actually Buy This Shit.” Chatter over the series grew with speculation that it was a classic Banksy move — to register on a NFT platform as an anonymous artist — and the works sold for a massive sum of $900,000. The hype only ceased when Banksy’s authentication body Pest Control issued a blanket denial of any relationship to Pest Supply. In response, OpenSea rushed to remove the works from its platform.

In a statement to The Art Newspaper, Pest Supply says their work examines “how value can be created from satire” and that they “meticulously create art that’s not the exact same copy of Banksy, but with style inspired by Banksy, and that works such as NFT morons “signify the current boom and frenzy within the NFT art market and how many collectors are caring less about works’ provenance and concept but instead more for a quick flip immediately after purchase… I am questioning the legitimacy of NFT art while using the art as a valuable test to test people’s perception of value, all done without mentioning a single word about Banksy or Pest Control.”

Inflated prices are not the only problem that exists in the space: what happens if the crypto platform that your owner certificate is stored on collapses? Blockchain entrepreneur and art collector Guy Bahat, who is currently building a new NFT platform is not worried. “The blockchain network can’t collapse, true the platform may collapse, anything is possible, but I don’t think it should bother anyone too much. We all sleep soundly enough with our money stored in a bank account that is a lot more susceptible to daily cyber attacks than the blockchain.”

Meaning that just as we don’t store paper money in the floorboards anymore, we don’t need to display the art that we purchased on the living room wall. But on the other hand, people still want to brag, show others what they’ve bought.

“There are framed monitors that people can use to showcase their files”

But you don’t get the files when buying a NFT, only the address code

“What I did was simply right-clicked the file and saved it as an image on my computer.”