Interview

Helios is powering lunar settlements of the future

The Israeli space tech startup’s proprietary technology aims to mine oxygen on the Moon, and power the next generation of settlements on other planets

The exorbitant cost of launching equipment to the Moon severely reduces the chances of building long-term settlements. Helios’ technology, ISRU, or in-situ resource utilization, aims to extract oxygen from lunar soil, while using metals to build and establish the infrastructure for future lunar and other planetary bases.

Helios is creating technologies that can help establish a lunar settlement on the Moon (illustration). Photo: Shutterstock

Helios is creating technologies that can help establish a lunar settlement on the Moon (illustration). Photo: Shutterstock “We don’t just want to plant a flag on the Moon and go back, we want to establish a permanent infrastructure so we need to utilize the resources available,” Jonathan Geifman, who functions as Helios’ co-founder and CEO told CTech.

The idea started nearly four years ago, when Geifman began to look into some of these technologies, and met with NASA’s former ISRU Project Manager, William (Bill) Larson, who later joined the company’s advisory board. ISRU technologies revolve around resource extraction, and excavation of consumable materials, as well as renewable energies.

The most sought after material in the foreseeable future is oxygen, not necessarily to breathe, but for space exploration and space settlement. “Average humans consume about 250 kg of oxygen annually, but if you compare it to what rockets will need for launch, those are pretty small numbers,” Geifman said.

SpaceX’s upcoming Starship reusable rocket needs to refuel itself in low-Earth orbit, and possibly on lunar or Martian surfaces too. When it’s fully-loaded, Starship is expected to weigh around 1200 tons, including the weight of the vehicle propellant, and cargo. Of that weight, around 800-900 tons is just oxygen. In order to run combustion for liftoff and landing, rockets need a propellant, such as methane, an oxidizer (which is oxygen), and heat. In simpler terms, every ton of methane requires around 3.8 tons of oxygen. “What humanity will do in space over the next couple of decades is basically just transfer a lot of oxygen from one place to another,’” he quipped.

As part of NASA’s upcoming Artemis mission to the Moon, where it plans on sending the first female astronaut and another male astronaut to the lunar surface in 2024, SpaceX is going to launch two lunar gateway modules. Currently, nearly 50 lunar missions are scheduled for the next five years, so there’s an urgent need for such technology, Geifman explained.

One of the main challenges of getting to the Moon is the extraordinary cost of sending anything to the lunar surface, where estimated costs stand around $1 million per kg, and many pay private companies to send their payloads to the lunar surface. “Obviously when Starship becomes operational that cost will be reduced by a factor of 10, but we’re still talking about hundreds of tons of oxygen needed to make that happen. If you run the numbers, it's economically unfeasible.”

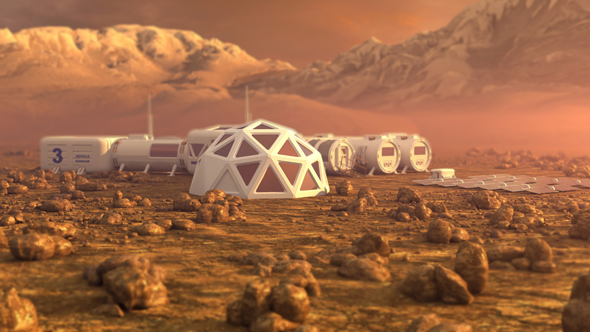

Helios hopes its technology can help build permanent settlements on the Martian surface (illustration). Photo: Shutterstock

Helios hopes its technology can help build permanent settlements on the Martian surface (illustration). Photo: Shutterstock How realistic is a future lunar settlement and when do you predict that will happen?

“I expect that within the next three to four years we’ll be launching several demos to the lunar surface, but they will be small-scale, and not on a commercial scale. We need to make improvements and alterations. We are simulating many aspects of the lunar environment here on Earth, but some things can't be easily simulated, such as lunar gravity. If I’m being very optimistic, I’d say it would take 10 years, either by the end of this decade or by the beginning of the next one, around 2030. I think things will go much faster than people realize,” he said.

Mining on the Moon

Helios’ innovative technology aims to mine the lunar soil, and extract oxygen from the Moon to use for rocket relaunches and constructing a permanent lunar settlement. That lunar regolith - a broad term for soil and loose gravel on the Moon - is abundant in oxides. Extracting those oxides for oxygen for combustion is where Helios comes along.

“In nature, most materials are bonded to oxygen; they are oxidized in their natural state. It's the same on the Moon. There are silicon, iron, aluminum, calcium, and titanium oxides, where oxygen comprises about 40-45% by mass of that material, and the same is true on Earth or on Mars,” he explained. Helios has developed a furnace that extracts those elements at very high temperatures.

“Normally it’s done with coal, but while effective that method also produces a lot of carbon dioxide and isn’t good for the environment. On the lunar surface, we don’t have coal, and don’t want to use a method that is very energy-intensive or pollutive. We want to be as efficient as possible,” he said. Helios uses molten oxide electrolysis to split the metal atoms from the oxygen. “We pass a current through electrodes through the regolith, and melt it, so we’re reducing the oxides, and splitting oxygen from the other materials,” he said. In addition to being energy efficient and adaptable on almost any rock solid planet, regolith is abundant from the Moon to Mars.

In order to test out its technology, Helios uses a lunar regolith simulant from the University of Central Florida, which produces such imitations of Martian, lunar, and asteroid-materials. The Israeli space tech startup also simulates the vacuum on the lunar surface, and the temperature gradient too. The only missing piece is gravity - since only ⅙ of the Earth’s gravity is felt on the Moon - and to answer that quandary, it currently has several trials that it plans on running soon.

The Helios team in the lab testing out their technology. Photo: Haya Gold

The Helios team in the lab testing out their technology. Photo: Haya Gold Far-out funding

Funding for space tech companies poses a particularly unique challenge - generating a proof of concept is far more complex when it needs to be successfully operable in space - without ever venturing into the far-reaches of the Universe.

So far, Helios has received funding from the Israel Innovation Authority, the Israeli Ministry of Energy, and the Israel Space Agency. It conducted a small seed investment round from some angel investors, and is planning on initiating another round in several months.

Helios was founded in 2018 by six co-founders, who serve in various positions including legal counsel, marketing, and technical positions, and its CTO Linoam Eliad who is an electrochemist with over 20 years of experience in the industry. The company is based in Hod Hasharon, and has a colorful advisory board including Yoav Landsman, former Project Deputy of the Beresheet lunar lander project and a Senior Systems Engineer at SpaceIL, Associate Prof. Brian Rosen, who heads an energy electrochemistry lab at Tel Aviv University, and others. Helios has several exciting space missions that it is set to participate in, but cannot disclose them at the moment.

The Helios co-founders and team at their offices. Photo: Haya Gold

The Helios co-founders and team at their offices. Photo: Haya Gold

How can Israeli space tech companies in particular contribute to the global ecosystem?

“I think that Israel probably has the highest percentage of space system engineers per capita in the world, and it’s thanks to Israel’s robust defense and aerospace companies, such as Israel Aerospace Industries, Elbit, Rafael, etc. You have a lot of engineers and experts here that really know the nitty-gritty when it comes to space, and there is a lot of human capital in that area.”

Geifman noted that he hopes that the civilian space industry will continue to develop in Israel, because he believes it will become one of the largest industries in the world. “Israel now has the opportunity to mark itself as a leading player in this industry. I also think that Israeli entrepreneurs have good connections, strong networking capabilities, and the right attitude to get things done.”

However, when it comes to funding, problems arise. “There aren’t a lot of investors and venture capital firms that know how to deal with space tech startups in Israel yet. It’s a very risky business. There’s a big funding gap from conception to proof of concept because of the nature of the industry. When you’re constructing hardware that will be sent to space, you need to test it in space which is very expensive.”

“Our research is in a very niche field, which is challenging since there are few experts or literature out there. A lot of what we’re doing is in uncharted territory.”