Interview

Capturing selfies in space to prevent satellite mishaps in real-time

“We’re bringing space to people,” says MicroGic Electronics CEO, whose company designs sophisticated cameras and sensors for satellites and other space applications

07:4110.12.21

Many things can go wrong in space. And keeping track of malfunctions or possible mishaps while above the Earth’s atmosphere is a very tricky issue. MicroGic Electronics, founded single-handedly by CEO Yoram Malka, aims to change that perspective by implementing a NewSpace mindset - making space technology cheaper. It designs sophisticated cameras and sensors that allow ground teams to see what happens to satellites in space in real-time. The small Petach Tikva-based company provides this hardware as well as consulting services to larger companies, whether they be in the medical, agritech, or aerospace realm.

MicroGic Electronics' selfie cam can take photos onboard satellites in real-time (illustration). Photo: Shutterstock

MicroGic Electronics' selfie cam can take photos onboard satellites in real-time (illustration). Photo: Shutterstock

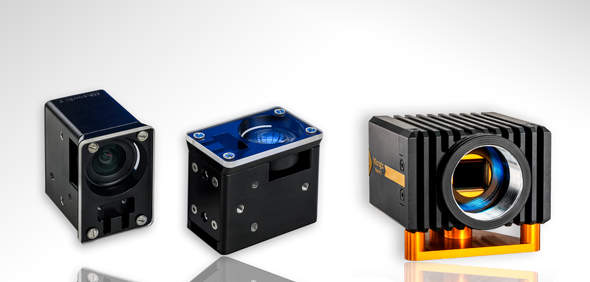

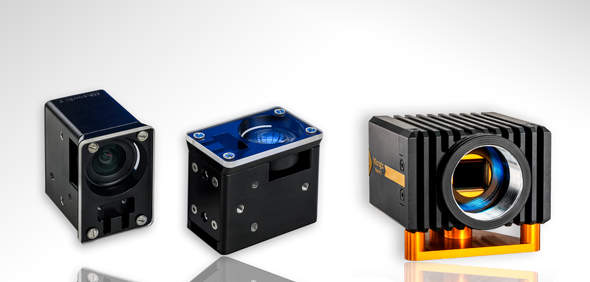

MicroGic's camera and sensor offerings including its "Ramon 2" camera (on right). Photo: MicroGic Electronics

MicroGic's camera and sensor offerings including its "Ramon 2" camera (on right). Photo: MicroGic Electronics

MicroGic CEO and founder Yoram Malka. Photo: MicroGic Electronics

MicroGic CEO and founder Yoram Malka. Photo: MicroGic Electronics

“We want to make space more accessible to people, '' explained MicroGic Electronics CEO Yoram Malka to CTech in an interview. “We want to bring space to more people, and change this concept that space technologies take a long time to build and launch, and cost a lot of money. We want people to know that more can be done with smaller budgets,” he added.

MicroGic Electronics' selfie cam can take photos onboard satellites in real-time (illustration). Photo: Shutterstock

MicroGic Electronics' selfie cam can take photos onboard satellites in real-time (illustration). Photo: Shutterstock MicroGic began in 2009 with a small staff. Malka previously worked on sensory imaging in the cellular phone industry, at the former-M-Systems with Dov Moran on the DiskOnKey, and later in the military and defense sector specifically in the area of ultra small cameras. Today, MicroGic has several offerings, namely its Ramon 1, 3, and 2 versions, and SWIR (Short-wave infrared) sensors, which operate between the visual and thermal spectrums.

Selfie-cams for satellites

MicroGic began building technologies for the defense arena, and moved to aerospace. One of its biggest projects included the BGU satellite, built by Ben-Gurion University of the Negev and Israel Aerospace Industries, featuring MicroGic’s camera onboard to monitor mishaps that may transpire in space. The research satellite was designed to explore atmospheric and weather phenomena in the infrared wavelength, such as atmospheric gaseous contents.

For another project, MicroGic worked with NSL Comm, designing small 14 megapixel cameras for the nanosatellites whose shoebox-size allows them to later deploy their large pop-up dishes in space, cutting down on weight, size, and cost. “When those nano-antennas open in space, they need to be constantly photographed to monitor their conditions, or whether there is some sort of malfunction, and ensure that they are working accordingly,” Malka said. “It also helps us better understand whether or not we need to move around some parts so that a proper satellite transmission can go through.”

That project has seen an exciting and unthinkable update: a selfie-cam for satellites so that spacecraft and other flying objects can self-photograph their own solar panels in real-time. “It’s similar to how people take selfies on their cell phones,” explained Malka. “When you send an item to space, it needs to be monitored - whether that’s the sensors, the current, electrical voltage, or temperature, since you can’t see what’s happening up there. Our selfie camera can keep track of whether something gets damaged mid-use.” But creating such a technology is far harder than it sounds. “Cameras in space need to deal with a variety of temperature fluctuations between -250 C (482 F) and 250 C (482 F). Nothing can survive those conditions, so we placed a stick with a mirror that extends from the satellite and can photograph the area behind the satellite.”

MicroGic's camera and sensor offerings including its "Ramon 2" camera (on right). Photo: MicroGic Electronics

MicroGic's camera and sensor offerings including its "Ramon 2" camera (on right). Photo: MicroGic Electronics So far, MicroGic has two other projects that have been delayed due to complications caused by the coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic. One is a collaboration with the Israel Space Agency to detect clouds and how they build up in the atmosphere, and involves engineering payloads to be deployed to clouds in space, to monitor how they change.

The company also has plans to join the Rakia mission, and partner on one of the experiments that the second Israeli astronaut Eytan Stibbe will take with him to the International Space Station in February 2022. That includes studying gamma rays - intense energetic explosions that have been observed in distant galaxies, are the brightest and most energetic electromagnetic events known to occur in the universe, and are believed to be emitted by supernovas and blackholes. A prototype developed by the Technion Institute of Technology, headed by Prof. Ehud Bachar, will include a MicroGic one-liter sensor to monitor these eruptions, and be placed outside of the station. It is being built by the Technion, but has been delayed due to Covid-19 restrictions.

Special sensors

The company also purchases SWIR sensors, recalibrates them, and installs them in satellites, imagers, payloads, CPUs (central processing units), powering controlling units, and other equipment in ways that suppliers do not fully understand. “We have that knowledge and data of how to work in space, and bring that to our customers,” Malka said.

“A decade ago, equipment used by the space industry cost between $100 million - $300 million, but with the NewSpace trend those prices are going down. We want everyone to be able to get to space. We’re bringing space to people.” As to making its products more cost-effective, he added that the company doesn’t utilize any specific unique material, which could be expensive. “We design our lenses to withstand a variety of temperatures, and have found cheaper material capable of protecting those lenses in space’s harsh environment. Our cameras are smart cameras; they’re constantly thinking ten steps ahead, and can shut down when they encounter a harsh temperature within milliseconds.” This is thanks to the automotive industry, which has been designing cars' electronics to be adaptable to different environments. “This helps the space tech industry obtain components that we couldn't get back in the day.”

MicroGic CEO and founder Yoram Malka. Photo: MicroGic Electronics

MicroGic CEO and founder Yoram Malka. Photo: MicroGic Electronics

MicroGic also provides consulting services and system designs to companies that encapsulate imaging models as a part of their devices, and need a more in depth understanding of the sensor architecture. It has assisted MedTech Netanya-based startup 270 Surgical to define the exact image sensors, and the mainframe architecture required in order to receive optimal image quality necessary for its endoscopic systems. The company 270 Surgical is currently starting its sales across U.S., Asian and European markets.

MicroGic isn’t only focused on the commercial space sector, but is also pioneering technology to protect the environment. In another venture, the company is focused on collaborating with the Netherlands and Germany to prevent oil leaks. “With our SWIR sensor technology, you can locate oil leaks very well and understand where they originate from and how to prevent or stop them,” Malka said, noting that sensors can differentiate very accurately between water and oil even in the dark.

Small yet mighty

Although the Israeli space tech ecosystem is far smaller in size than its counterparts, Malka thinks that its uniqueness lies in the swiftness and speed with which it embarks on new projects in space, and brings them to fruition. Malka recalled how he recently spoke with camera suppliers in space industries from all over the world, who relayed that they would only be sending their technology to space in another two years. “The industry in Europe and the U.S. gets things done far slower, but in Israel we work fast. If a customer comes to us and wants to send their technology to space in a year, we make that happen.”

The company is privately-held, and currently does not have any solid plans to go public, but that is one of its future goals. “If you want to play on the big field, you need proper financing, and need to break that glass ceiling.”

Read More:

- Former partners of Israel’s first “space tourist” demanding over $300 million in compensation

- “We like to call ourselves the Space X of weather-tech”

- “People don’t realize that every time we swipe a card or navigate a car we’re accessing space tech”