BiblioTech

CTech's Book Review: A call to raise our children without gender constructs

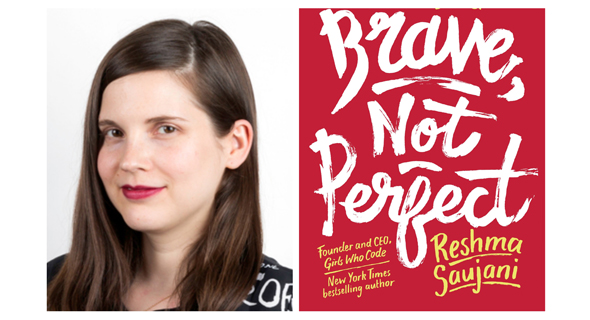

Shachar Orren, Co-Founder of EX.CO, shares insights after reading “Brave, Not Perfect” by Reshma Saujani

Title: “Brave, Not Perfect”

Author: Reshma Saujani

Format: Audiobook

Where: Commute

Shachar Orren is the Co-Founder of EX.CO. Photo: Caroline Sino/Amazon

Shachar Orren is the Co-Founder of EX.CO. Photo: Caroline Sino/Amazon Summary:

According to social research, some of the differences between men and women are biological, but many others are the result of social constructs that revolve around us from a very young age, maybe even from the very moment we are born. The author of “Brave, Not Perfect” Reshma Saujani - who is the Founder and CEO of non-profit organization Girls Who Code, aiming to close the gender gap in tech - talks about the fundamental difference in how boys and girls are raised, and how that impacts our performance in the business world when we grow up. In essence, Saujani claims that while boys are taught to take risks, to try and fail, girls are raised to simply be perfect. The impact of those different ways of upbringing on how we operate is much more meaningful than you would imagine.

Important Themes:

Saujani begins the book by telling the story of how in 2009, after a few years behind the scenes in the political arena, she decided to make a crazy move - run for congress in New York City. She was perceived as a rising political star, raising money from everyone she had known in a total of over one million dollars, being covered in major newspapers as a promising diversity candidate - but eventually reached merely roughly 6000 disappointing votes and, naturally, lost the race. While the failure was humiliating, it made Saujani realize that this experience aged 33 was the first time in her entire life that she had done something truly brave. Where she didn’t worry about being perfect.

Saujani tells this story because it also made her realize that she was not alone. She also realized that so many amazing, talented women around her, would only go for careers they are convinced they would be perfect in, that are within their comfort zone. This is what started the “Brave, not Perfect” movement. “Most girls are taught to avoid risk and failure, to smile pretty, play it safe, get all A grades,” Saujani writes. “Boys on the other hand are taught to play rough, swing high, crawl to the top of the monkey bar, and jump off headfirst. By the time they are adults while negotiating a salary or even asking someone out on a date, they are habituated to take risk after risk. They are rewarded for it.”

The book was recommended in a women’s network that I’m part of, and something about the title struck me immediately. Listening to Saujani’s words (I highly recommend the audiobook narrated by the author herself), reminded me of how the decisions I was most proud of in my life were the ones that I, or the people around me, considered brave. Like switching industries and roles with little to no experience or preparation. Or jumping head first off the monkey bar into an early-stage startup rollercoaster, leaving behind a 9-year long journalism career in which I had already built a name for myself.

- CTech's Book Review: Learning to overcome life’s inevitable challenges

- CTech's Book Review: Setting the foundations for a successful career

- CTech's Book Review: Examining the methods to our madness

What I’ve Learned:

“We’re raising our girls to be perfect, and we’re raising our boys to be brave.” The most important lesson from this book made me look at the powers and influence at play in the way we raise boys and girls and how it influences their future. I think about the impact it must have had on how I had been raised, as well as the strong, successful women around me. Remembering girls in school who didn’t want to play in the mud so that they won’t get their dress dirty or refused to jump in the pool to avoid messing up their hair. I also remembered what a good job my parents did, when they convinced me to go to a group sports class and play tag when I was 4 or 5, even though I had literally been terrified of being in the losing group every single time.

Saujani claims the “bravery deficit” is a big part of why women are underrepresented in politics, in the C-Suite, in Boards, and pretty much everywhere you look. Women have been socialized to aspire to perfection, which makes them overly cautious, and tend to escape potential failure. As a woman in the startup world, this is a painful realization, especially knowing that failing is what happens to most startups. In fact, the common belief is that in Silicon Valley, no one even takes you seriously unless you have two failed companies under your belt.

A surprising fact to discover was that research shows that smart girls are more prone to giving up on a task when they feel they are not going to do it perfectly. The higher the IQ, the more likely they are to let go. Bright boys, on the other hand, enjoy the challenge and double their efforts. This is not a question of ability - while in school, girls routinely perform better than boys, but that’s because the rules are clear and defined - there’s a scoring system, and the path to get the perfect score is simple to outline and dependent on dedication. However, once we come out into the business world, there’s no one clear path to success, and definitely nothing is ever perfect.

In the real world, bravery gets rewarded. You know the clichés: go big or go home. Fortune favors the bold. Giving up on something you’re not yet great at will get you nowhere. It’s why men apply to a job when they meet only 60% of the criteria, and women, on average, will apply only when they meet 100%. Ever since reading this book, I find myself quoting parts of it to friends who have daughters, to colleagues and people on my team, and many times, to myself when I debate whether I should take a risk that would push me right out of my comfort zone. Being perfect sounds lovely on paper, but it’s very unlikely to get you anywhere.

So how do we build our bravery muscle? Here’s another big takeaway from Saujani: “Surround yourself with rejection. One way we build back our resilience and take the sting out of rejection and failure is by normalizing it. Display your rejections proudly, they’re a mark of your bravery.”

Critiques:

While I agree that lack of failure experiences and bravery is part of why women are underrepresented in tech and many other industries and positions, it wouldn’t be right, or would be rather simplistic, to reduce the problem to this issue alone. Social constructs are impacting men and women in many different, hidden ways, that even when women, or other underrepresented voices, choose to take a risk and participate, they are not always welcome and invited, or have the capability to do so.

Also worth noting that while lessons in the first half of the book are very meaningful, the second half can be somewhat repetitive, and doesn’t deliver many new groundbreaking insights as the first part does. So if you’re short on time, feel free to skip the second part, you will still get the core.

Who Should Read This Book:

I strongly recommend that women in tech, but also other women or men, read the book in order to better understand the forces that operate to make us who we are and impact our risk-taking behaviors. I truly believe that the reading endows us with an important prism, to consider whether we should be more aware of our own decision-making processes, and more aware of what we say to our children in the understanding that it may well influence them in the future.