"Hamas used rape to break up the entire Israeli community"

A feminist gender researcher, a religious woman with a headscarf, and a settler who demonstrates against settler violence, Dr. Nomi Halbertal Landau has been researching sexual violence in the context of genocide, from Rwanda to Bosnia. Now she explains why the events of October 7 requires us to go out not only against the terrorists, but also against the entire patriarchy

"When reports began to arrive that on October 7 that there was a second wave of looters, I knew that there was no way that women were not harmed. Why? Because historically, the second wave is a phenomenon that repeats itself in every genocide: the first wave enters, makes the people defenseless, then the civilian population joins in and commits a second wave of crimes against humanity, which is sometimes more severe than the first wave. This happened in Ukraine during World War II, when the Nazis invaded and made the Jews extremely vulnerable, and afterward Ukrainian citizens arrived and abused them; and this also happened on October 7, when Hamas terrorists entered the settlements around Gaza and laid the groundwork for the civilian population to come and loot. Then I said: Okay, it's already entered a pattern, it's no longer a terrorist attack, it's something else: it's genocide that didn't succeed, because we're still here."

The speaker is Dr. Nomi Halbertal Landau (39), a gender researcher and historian, who has been focusing on sexual violence in the context of genocide for nearly a decade. Her doctoral thesis on the subject was recently adapted for the book In the Jaws of the Patriarchy (Carmel Publishing, June 2024), in which she analyzes the testimonies of Yazidi, Rwandan Tutsi, Armenian, and Bosnian survivors of sexual violence. In her research, Halbertal Landau provides important lessons for dealing with the survivors of Hamas's sexual abuse, and she presents the reader with a sharp indictment not only against the abusers, but against patriarchy as a whole.

It is not obvious that such an indictment would be filed by a religious woman who covers her hair, but Halbertal Landau is the scion of a lineage of intellectuals who buck convention: her mother is Prof. Tova Hartman, a gender researcher, Dean of the Faculty of Social Sciences at Ono Academic College, and a founder of the Shira Hadasha egalitarian community in Jerusalem, which has redefined the place of women in Orthodox synagogues; her father is Prof. Moshe Halbertal, a widely respected Hebrew University philosopher and ethics scholar who, among other things, spoke out strongly against the judicial reform of 2023; and her grandfather, Rabbi Prof. David Hartman, who was one of the leaders of the liberal current in Orthodox Judaism.

"In my master's degree, I read testimonies of Jewish rape victims who tell about their religious struggles in the Holocaust, and among many of them there was fear, specifically of their family, in some cases even more than of the abusers," Halbertal Landau says. "Jewish law allows a married woman who has been raped to return to her home, but among the rabbinic decisors there is a debate about the definition of rape - if it applies only in the case of physical coercion or also in the case of a woman who consents to sexual relations in order to save her life. These definitions are of great importance in religious communities, since the woman who has fallen victim to rape may also find herself excluded from the community and limited in her ability to marry another man.

"That's something I wasn't taught," says Halbertal Landau. "I didn't know that when sexual violence is threatened, the family - the fathers, the brothers, the rabbis - become scary, because you don’t know what they'll decide and what they'll do to you: they might prefer that you be killed rather than raped, and you know that they won't allow you to return home. I suddenly realized that there is a double injury and trauma for women here."

"In social structures dominated by men, the rape of women is interpreted as an injury to men, to their dignity and their ability to protect their wives, and not only as an injury to women themselves as subjects. In addition, sometimes the ethical code of the community requires women to be ostracized or deported in a way that breaks up families. Therefore, the attacker who injures the enemy’s women sees this as a violation of the basic structure of the victim's community, and so sexual violence cannot be interpreted solely as an act that accompanies the general breach of moral and human boundaries that occurs during war, but also as a planned and organized act whose purpose is to undermine the community until its destruction - that is, sexual violence is a weapon that is used in the service of the main goal of genocide. The patriarchal mechanisms of the community are used against women."

"What happened here on October 7 was an attempt to terrify people to the point that they could not return to their homes. And in my careful assessment, whoever harmed the women at Nova thought that they would be defiled."

The attack by Hamas is very different from the genocides you analyze in your book.

"True, these are different cultures and other motives. In Rwanda, for example, the genocide is more related to the colonial occupation of the Belgians that was there, in Turkey it was a Muslim power that turned against a Christian minority within it, etc. But when you dive into the cases, you see that there is a connecting thread, which is a horrific attempt to destroy a community through sexual abuse - to present the men as impotent and turn the women into slaves or wombs for the benefit of the other party."

That is, to use the mechanisms of the patriarchal community to dismantle it from within.

"Exactly. And the language repeats itself in what the victimizers say to the victims; for example: 'You will be the mother of many Muslim men,' 'We are doing to you what we would never do to our women,' 'Nobody will want you,' 'Where will you go? You have nowhere to return to'."

These are things we also heard in the testimonies of abductees who returned, who were told "there is nowhere for you to return".

"Yes. And even if they are not told this, it is very clear to them that after the rape, the woman has no place to return to."

In the book you explain that according to the laws of the Yazidi religion, the women who were raped in ISIS captivity become Muslims, meaning they no longer belong to their community. But unlike them, the Israeli survivors have where to return, and there is no fear of double harm.

"We are still in the event and we still don't really know how the survivors will be accepted in our society. True, we are not Armenia of 100 years ago, and girls who were raped by Hamas terrorists will not be murdered here, but this is a serious warning sign of how societies can quickly fall apart around these things. It is important to remember that this also happened in relatively “western” Bosnia, for example, and we are not far from it. We need to be on guard and not say 'we have no such fear because we are a more secular and modern society.' Because the patriarchal mechanisms are so strong in relation to a woman who has been raped: people start speculating about what she did to save herself, what will happen if she comes back pregnant, and how the child is treated. In and of itself, our attitude towards rape as a point of no return is dangerous."

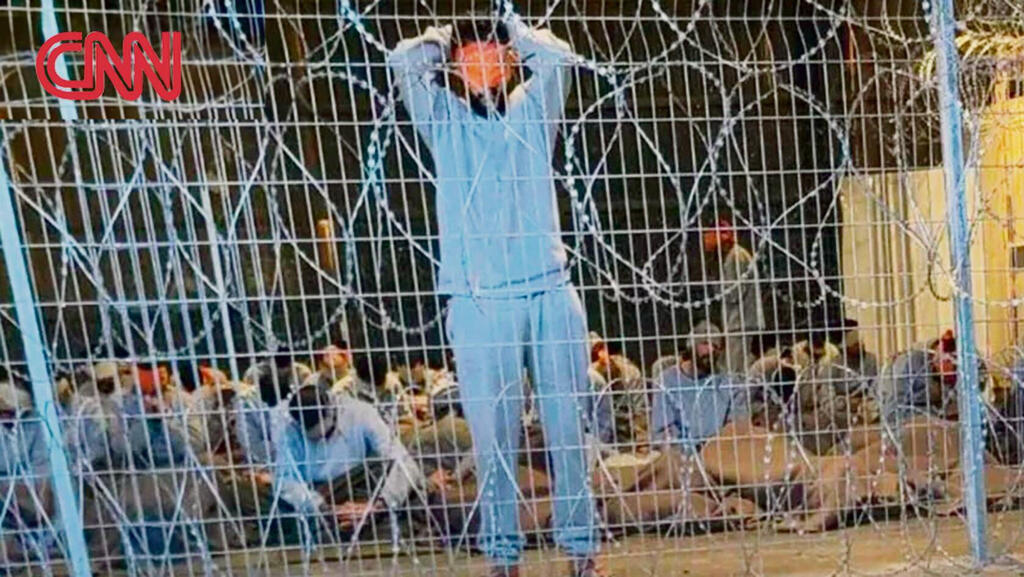

And even though we are a modern society, people here broke into an IDF base to defend the right of reservists to sexually assault Hamas detainees.

"True. Israelis are not above anyone in this matter. My book is a warning sign for all of us. We are not different, we are not innocent, and we need to be very careful. That is why we must punish those soldiers with the utmost severity."

What can we do to better care for survivors of sexual assault?

"We must be careful to treat survivors not as martyrs but as human beings with a story, with a trauma that stems from, among other things, our total failure to rescue them earlier, and remember that we do not know the exact details of what happened, and that we must give maximum respect to them and their pace of recovery."

"This is how PC queens speak?"

Halbert Landau grew up in Jerusalem and Boston, and she currently lives with her partner Eliad, a high-tech product manager, and their five children in Tekoa. She has a bachelor's degree in dance from the Academy of Music and Dance in Jerusalem, a master's degree and a doctorate in gender and history from the Hebrew University, and another master's degree in business administration. She is currently a lecturer at the Faculty of Education at Ono Academic College and VP of Business Development at the start-up COB (Communities of Business), which is developing an artificial intelligence job-placement system.

Her unconventional life path also includes getting an aliyah to the Torah at the age of 12 ("I was one of the first Israeli girls to get an aliyah," she says with a smile), volunteering as a foster family, and organizing demonstrations in Gush Etzion to protest settler violence against Palestinians ("I took Ben-Gvir's rise really hard... I'm really ashamed," she told "Liberal" last year).

Last year she was invited to be a visiting scholar at Columbia University, but within three weeks it was over. "That is the most uncompleted post doctorate ever," she says, laughing. "I was a visiting scholar in gender and human rights, and the plan was that I would stay there for an entire semester, but on October 7 my partner was drafted into the reserves, so I returned. I didn't have time to mingle at all."

It is doubtful whether she would have even wanted to mingle in light of the reactions she received later, when she published an article about the sexual violence of Hamas. "I sent the article for peer review and one of the responses was that I sounded angry," she says with a bitter smile. "That is the most politically incorrect thing to say to a woman; it's been forbidden to talk like that for 30 years. But because of the very dichotomous concept of victim and victimizer, the thought is that we Israelis are victimizers, so we don't have any victims. It's simply tragic. There is no recognition that those who were in the bomb shelters are victims. That disbelief really stunned me."

What did you write in the article?

"I presented the testimonies of Israeli women alongside the testimonies of Yazidi and Rwandan women in an attempt to place them on a historical continuum, to show that what happened on October 7 was not a terrorist attack but an attempt to drive people from their lands, to frighten them to the point that they will not return. Otherwise, why abuse people that way? There were crimes against humanity. This of course does not mean that it is not possible to criticize what Israel is doing in Gaza, but that’s a different matter."

"My article is still being updated and things are being added to it, such as statements from the recording of Hamas's remarks about the female observers in which they called them 'Sabaya' (“maidservants”) and said: 'These are girls who can get pregnant, they’re that age.' It's the same conceptual world I know from genocides - it’s not terrorism."

Beyond Israel's precarious international status, one of the reasons for the academic opposition to research on the victims of Hamas' sexual assaults is the demand for "golden evidence" - conclusive proof that sexual crimes were committed, which is difficult to obtain due to the nature of the crime. "They are constantly trying to find the one who will stand up and say 'I was raped,'" says Halbertal Landau. "This attempt by academia and the media to pry and to bring women to testify is terrible, because it intensifies the trauma. You have to give maximum respect to the victims and understand that we are still at the heart of the event, and we need time. And also we need to believe that it happened, to understand that this is what evidence of sexual violence in genocide looks like - it is heard and not heard, said and not said."

Like the Yazidi who told you in the book that "the men did everything to her" but she can't tell what they did to her, and in the same breath she really wants to tell the world what happened to her.

"Either she will tell me in great detail what happened to her but not who she is and what her name is, or she will not want me to write what village she is from. That is a prototype of testimonies about sexual abuse. They are full of fragments and silences. There is something so complicated in the way the testimonies are given, and we see this a lot in the survivors of October 7th because we know it happened, and it was said and not said. And then in reaction to this, the question arises: Did it happen? Did it not happen?"

We have a survivor, Amit Soussana, whose clear testimony about the sexual violence she experienced in the captivity of Hamas made waves in the world, and still, somehow, the issue arouses serious disputes in media outlets such as the New York Times.

"True, we have Amit and in my eyes that is more than enough, yet we are constantly looking for more."

And then your colleagues question it.

"Right, they really put this thing in question, or compare it to other things, saying 'Oh, it doesn’t just happen to you.' True, it is clear that terrible things are happening in Gaza and that we must take stock, but my colleagues should know that we don't talk like that. And this is where the patriarchal mechanisms become relevant, because the world's reaction is as if we have gone back decades in time. For paradoxically, my colleagues in the field of gender are suddenly saying things like 'Did it happen? Did it not happen? They are exaggerating.’ These colleagues are using ultra-patriarchal language, and I say to myself: 'Wow, what is this? What does this have to do with how we behave in Gaza? Are you justifying rape in some way?' There is a hint of justification, and this is where these patriarchal mechanisms are activated, like telling me that I sound angry in an article I wrote. Tell me that the article is not accurate or argue with me academically, but to say I sound angry? Of course I'm angry! So what? You don't talk to women like that anymore. You PC queens suddenly talk like that?"

"We are still inside the event, so we don't know what happened and how, and it will take a long time. In the Lahav police unit they work very hard to collect everything. But we must understand that there is no ‘golden proof’; it is often broken testimony, which has a lot of silence, which may lack details and is apparently incoherent, due to issues of shame, anonymity, or simply trauma, which is typical of this type of testimony. This is what makes the evidence of sexual assaults unique. If there is evidence like this then you know it happened, meaning that there is a reversal here: precisely if you have these fragments then you know that this is it. And my colleagues know all this. Like me, they studied in gender seminars. Some of them are more professional than me. It's the ABCs of feminism."

Why do they still require golden proof?

"First of all, because Israel is giving itself the worst possible public relations. Second, because there has been a very rigid concept of victim and victimizer, and once you are a victim, anything can be done to you and you are not allowed to say anything. This is a total lack of understanding. They want to tell me that the female surveillance soldiers are not victims because we have an army? What planet are they from?"

"And also: What kind of wretched perception do they have about victims? What, they are not human beings, they have no choice? It is a kind of racist perception toward victims, which reduces a human being to a slogan, and turns them into a person who is not human. What, the Gazans can't choose? They are rape machines? What kind of nonsense is this? You are allowed to lock up citizens in your homes and not let them eat because you are a victim? You can murder them in front of their parents because you are a victim? That is a concept that outrages me as a person."

"We must scream the another religious voice"

The conversation with Halbertal Landau is full of surprises, befitting someone who wears a multitude of contrasting, or seemingly contradictory, hats. "I am a person with a million voices inside me. I have many hats and many voices," she says. Such a surprise arises when she talks, for example, about the war in Gaza from her home in Gush Etzion. "I think that October 7 is an event that should change all of us, the entire Israeli society, where we are going, what is the discourse, what is the language. And the importance of the two-state solution is so great now. We have no choice but to choose the path of the two-state solution."

How are these perceptions received in your community?

"The community that I live in is a diverse community, but I am in a minority position of course."

How does the community receive your book? In it you express serious criticism towards patriarchal mechanisms.

"Let's talk more deeply: I am religious. I think the bigger question for me is not the community but me. There is a great complexity here regarding patriarchal concepts: Why do I cover my hair? Why do I send my daughters to religious schools, which educate about concepts of modesty? But I feel like I'm finding my way and my interpretation within these structures. I grew up with a very feminist mother who founded egalitarian synagogues. I've experienced this tension all these years, and I'm not ready to give up Judaism. As I often say: I’m in a wide straddle, sometimes it's too wide, let's see if I don't go crazy,'" she says and laughs.

"I feel that right now we must scream the other religious voice. The one which represents us in politics does not represent me from a religious point of view - so precisely now I will wear a head covering, it is important to me."

At the beginning of your book you write that "the patriarchal propaganda is no less serious than the racist propaganda." What do you mean?

"We very much understand racist terms that need to be fought. In Rwanda, for example, it is completely forbidden to say whether you are Hutu or Tutsi, in order to fight genocide. So equally we need to understand that when you tell a daughter that her virginity is the most important thing in the world, or that if she is raped she has nowhere to go to, or when we sanctify the purity of the modest daughter--the meaning of all these in the case of sexual assault is death for her."

"At a certain point I thought to myself: how is it possible that all these amazing women end up showing up in my work just with their initials, as S, E, and B? It is clear that this is their wish, and I will respect it completely - but this thing needs to be fought. What did they do that they have to hide?"

In other words, the problem is in the system, which silently accepts the dangers posed to the lives of the survivors, instead of making sure that they get the protection they deserve.

"Right, why do they have to testify in court, and why does the system accept it? They didn't do anything, on the contrary. These are just women who want to live their lives. They are real heroes.

"The book was written with my heart's blood. And I wrote it during a difficult time in my life, after I had a miscarriage. The women's testimonies really lifted me up, gave me strength. If I said to myself at a certain moment that I didn't want to get out of bed, I reminded myself that that survivor did get out. If I was having a bad day? Remember that these women’s parents are illiterate and yet they know how to read and write in German, so let’s go: charge ahead."