Inside the mind of Israel’s cyber queen: Tal Kollender’s unlikely path to success

From a teenage hacker to the founder of GYTPOL, Kollender’s journey was anything but ordinary.

"The scheming gene is present in everyone, but it doesn’t manifest in everyone," says Tal Kollender, founder and CEO of the cyber company GYTPOL. "Most people are not aware that they have such a talent, and even those who do don’t always know how to take advantage of it. But I always had a desire to explore, to understand, and to find a way to win, because losing was very difficult for me. So from childhood, I would look for ways to bypass the system, to manipulate it in order to get what I wanted."

When did you realize you had this talent?

"From a young age. Monopoly and card games were very easy for me, like those who say they have a poker face. I was the only girl in the neighborhood who played soccer with the boys, and when computers and the internet arrived, the action shifted to all kinds of flash games with competitions. When I was 13, a mineral water company organized a flash game competition, and the grand prize was water for a whole year. I tried my hand at the game and did well, then I went to sleep. The next morning, when I woke up after three or four hours of sleep, I couldn’t believe my eyes when I saw that someone was ranked above me. It made no sense to me. I knew he had pulled some kind of trick, and I had to figure out how to do it. I remember saying to myself: 'If he can do it, then I can too.' That’s where it all started."

What did you do?

"I went behind the scenes of the game, into the database where the data was stored, and I placed myself in first place."

How did you even know how to hack the system?

"We learned a bit about coding in seventh grade, and it really interested me. So I thought: if there is a line of code that should make the button perform a certain action, what if I could write something else to make the button do a different action? The website for the competition was written in HTML, so it was easy for me to penetrate its backend and inject a query into the code, which manipulated the information in the database and caused my name to rise in the rankings."

Did you care that it was cheating?

"No, because it was clear to me that I was competing with other cheaters. The competition was basically about who was the biggest cheater—who was the best at manipulating the system. I realized that playing normally wouldn't lead me to anything. And the brain only degenerates from that. And that’s where smartness comes in—not just in computers, but in other areas of life as well. Even in school, I was a good student, but I didn’t just bang my head against the wall. I was always looking for ways to be smarter and make things more efficient."

That competition planted the seeds of troublemaking in Kollender. "The water bar I won was just the beginning," she says. "Later on, I won prizes in many more competitions without actually playing. At one point, I even handed out the prizes to others. I felt like the female version of Robin Hood."

Were you ever caught?

"When you’re always ranked first, you have to use fake names. But even using several different names on the same email address doesn’t look good. So I used the names and addresses of friends. Those who played for real—they lost. They were playing against hackers without even knowing it, because it was easy to break into those games. I was always looking for more sites with more games, and my appetite grew for bigger, more interesting challenges."

Where did you find that challenge?

"I started hacking chat apps, then emails, and from there I moved on to hacking other computers and cell phones. One thing led to another. Each time I thought, 'Let’s go for something bigger.' And when you meet friends in the field from online communities, it helps you improve. You acquire expertise out of curiosity and research. Back then, they didn’t call it cybercrime, but today you would go to jail for such things."

Did you make money from it?

"No. Even though I was able to access websites that stored full credit card information, I didn’t trade the information or use it. I just wanted to prove to myself that I could."

4 View gallery

Receiving the Entrepreneur of the Year award from the United Cyber Security Alliance, Las Vegas, 2023

Think like an attacker to defend

It’s rare to hear a monologue from the CEO of a cyber company openly discussing her exploits as a hacker in her youth. But for Kollender, now 36, these experiences are filed under “nonsense I once did.” Today, almost 20 years after she switched to the legal side of hacking under the IDF’s guidance, she is one of the most significant cyber experts in the industry, and one of the few senior women in the field. Last year, she even won the title of Entrepreneur of the Year from the United Cybersecurity Alliance, awarded at a ceremony in Las Vegas.

GYTPOL, the company she founded in 2019 with Gilad Raz and Yakov Kogan, primarily deals with entry breaches in organizations. According to a 2022 Microsoft report, these breaches are responsible for 80% of ransomware attacks, ranging from easy-to-exploit security settings to outdated software that lacks security updates and violations of organizational guidelines on computer usage. "The problem is that no matter how strong your antivirus is, attackers know how to bypass it and move around your organization without being detected," Kollender explains. "To defend against them, you need to think like an attacker—to understand what they will exploit and how they will find the easiest way to enter the organization. We simulate attacks on organizational systems, and to our surprise, we find that the defense mechanisms don’t see us as a threat. This means they wouldn’t detect a real attacker either. When we identify loopholes, we automatically close them, and when necessary, we add a line of code that seals the gap."

The company is based in Tel Aviv and employs 40 people—half of whom were recruited in the last six months. According to Kollender, GYTPOL has more than 300 clients, including Carlsberg, Colgate-Palmolive, and Kraft-Heinz in the United States, as well as Check Point, Clal, El Al, Sheba, Strauss, Phoenix, Hadassah, and the Maccabi, Clalit, and Meuhedet HMOs in Israel. "In 2020, we were three people handling dozens of customers, but three years ago, when Check Point became our customer, it helped us break into the U.S. market," Kollender says. "That was our first step into the American market. Today, we have over $10 million in sales, and by the end of the year, we will reach $20 million—all without raising a shekel."

Did you invest private money in the company? Your co-founders have all had successful exits before.

"No. No one has invested money in the company except for the customers."

Did you have doubts?

"People told me I wouldn’t succeed because what we developed was ‘a feature, not a product. It’s something small.’ That just gave me extra motivation. If someone tells me I can’t do it, I’m determined to prove them wrong. In the first two years, the product was considered a ‘nice to have,’ and organizations treated it as secondary. Today, they see it as a ‘must have.’"

"What Tal has done is very impressive," says a senior industry official. "At a time when entrepreneurs are raising millions of dollars and burning through it, her company is a true bootstrap—there aren’t many like it. GYTPOL creates a clean work environment for large organizations by addressing problems stemming from misconfigurations. If all endpoint security products did everything they promised, there wouldn’t be a need for GYTPOL. It’s true that it doesn’t create a new category in cyber, and it won’t solve the next AI problem in the industry, but it does solve a real issue in large organizations—and the product works. There are enough companies that sell you the moon. GYTPOL doesn’t sell dreams; it solves a problem."

Dad was a P.I., daughter is a hacker

Kollender currently lives in Tel Aviv, but she grew up in Rosh HaAyin until the age of 12, when her parents divorced. "I went through a lot of difficult experiences during that period, and I had to toughen up," she says. "Divorce is an economic blow that creates survival challenges, and I saw my mother forced to work several jobs, including cleaning stairwells, so that we could eat a hot meal, go to a movie, get new books for school, and buy a computer."

Did the divorce make you want to "beat the system"?

"It made me realize at an early stage that life is not always what you want it to be, and it taught me to appreciate what you have. It may also be that coming out of a difficult situation with a sense of control led me to develop creativity, out-of-the-box thinking, and the belief that I could conquer every mountain, even if it was really hard and took time. It made me understand that you can lose everything in a second, and you have to make an effort to protect what you have."

Is your father still in the picture?

"Yes. He has also always been a big influence on my way of thinking. He worked as a private investigator, investigating things like marital infidelity and insurance fraud. In his role he always had to find a way to be clever in order to get to the truth, but in a way that he would not be found out. And what he did in the physical world, I applied in the virtual world."

How did your mother influence you?

"She taught me to be a workaholic and take care of my family above all else. For years she worked in procurement, day and night. Until my father got cancer, when I was 24. Then she quit her job to work shifts with us and treat him until he passed away, so that my brother and I could also take care of ourselves and work. He was her divorcee, and she did it purely for me and my brother, because what is a family for?

"Even today, when she is in a difficult state of health, and my brother and I accompanied her during the surgery, the first thing she said when she opened her eyes in recovery was: 'Have you eaten?'. Even in her most difficult moments - the children are what is most important to her."

Kollender’s transition to the cyber field began in the army, when she was recruited into a classified unit, which required her to receive a strict security clearance. "I had to detail in the questionnaire all the nonsense I did, but there was no room on the page for so much detail," she says with a smile. "Then the person who handed me the questionnaire told me: 'Leave it, it doesn't matter. We already know everything. When you get to the polygraph, say 'I sinned, I committed a crime, I'm not there anymore. The country is important to me'. And be true to that. Stop helping yourself, and start to help your country'. That's where I changed the way I thought about things."

How did the army know what you did?

"In retrospect, it became clear to me that for the purpose of the clearance they spoke to people I didn't know they spoke to. And when people hear 'Shabak' (Israel Security Agency) they immediately spill their guts. From that point on, I stopped doing non-kosher things."

Is it possible to turn off the criminal part of the brain so easily?

"Definitely. I received a security clearance at the age of 18, and I will never misuse it. Today, my scheming gene is used to do good."

And what about the hunger to win at all costs?

"I got better at it, but to this day if, for example, I fail to recruit an employee I wanted or I lost a client, even for a technical reason - it's hard for me to accept it."

It all started with a scribble on a napkin

After five years of military service, Kollender returned to being a civilian and worked as an employee at Netcom, Avant and Dell EMC. While working at Dell, she founded a startup in the field of social transportation as part of a startup accelerator for smart cities. Her partner in the venture, whom she met at the accelerator, was Gilad Raz, who was part of the exit of Digital Fuel for about $120 million in 2011.

When the shuttle venture failed, Kollender decided to quit her day job to invest all her time in her next venture. “Already at Dell EMC I wanted to make GYTPOL a service to be sold to customers, and not as a product. The company said, 'Sounds good! We'll take the idea,' but they didn't do anything with it , because in a large organization you have to go through countless approvals, and everything you want to do they give you a hard time. I broke down and I decided I wanted to start a company."

What did you do?

"I explained the idea to Gilad, and he asked that I first meet Yakov Kogan, his partner in the exit of Digital Fuel, and convince him. Gilad goes with his heart when he believes in a person, and he believes in a partnership between us. But Yakov acted out of dry logic, and he told me, 'I am skeptical, I can't find materials on the net about the problem you describe.'

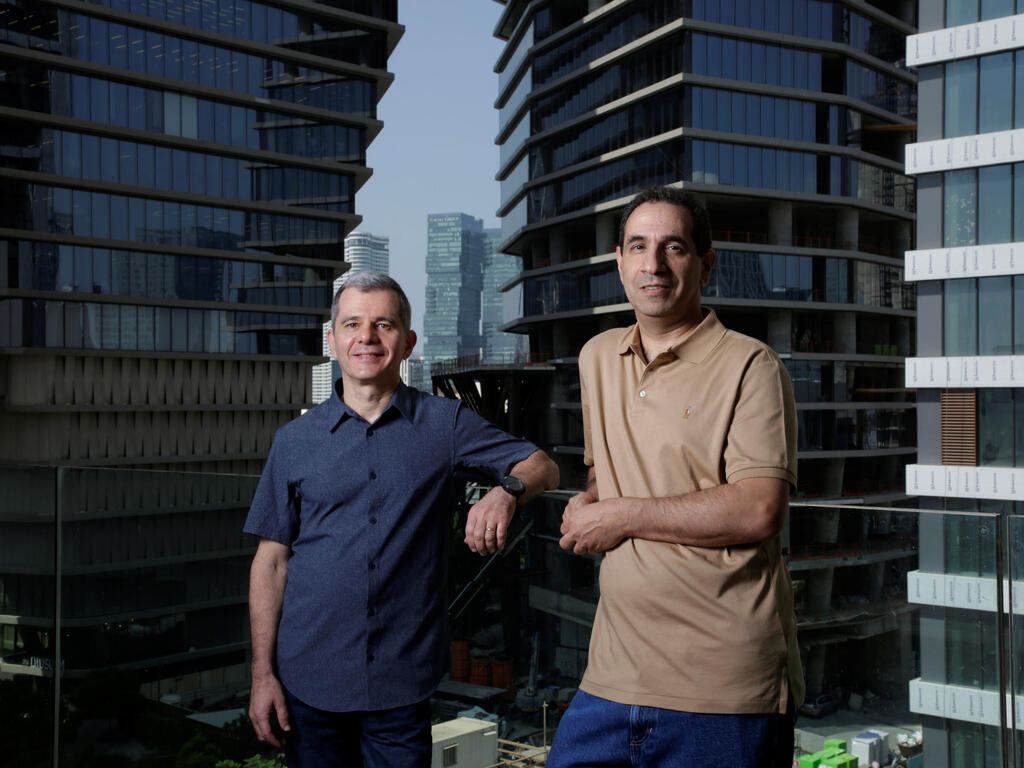

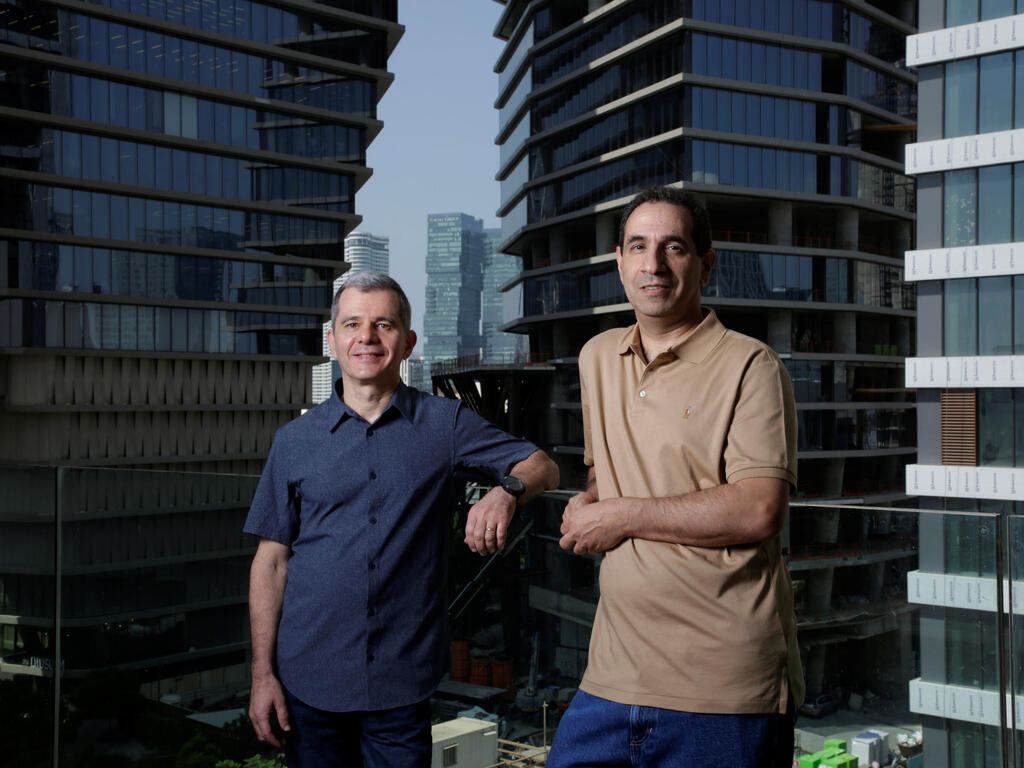

4 View gallery

Kollender's GYPTOL co-founders, Gilad Raz (right) and Yakov Kogan.

(Photo: Ryan Preuss)

How did you convince him?

"I met in a pub with Tal Catran, a friend who works in establishing accelerators for start-ups. I sketched for him on a napkin the plan for GYTPOL, and told him that I believe that everyone needs this solution. He lit up and connected us to a huge potential customer - Israel Aerospace Industries (IAI). And when we got to the first meeting with them they were so enthusiastic that Yakov was shocked and said 'I'm in'.

"In February 2018, we released the first version of our product and IAI bought it for three years, and in 2019 we officially established the company and went to market. The name GYTPOL is made up of the initials of the three of us and 'POL’;- short for Policy. From there we slowly grew."

How is it that you are the face of GYTPOL? Your partners are more experienced than you.

"Yakov and Gilad are the elders of the tribe, they were already there, made an exit, and were not looking to become CEOs. They saw my passion and motivation, so they said 'take the lead'. But they also try to keep me from going too far. They know from experience how harmful it can be to your health."

When does the load become too much?

"I don't have a problem with good pressure, but when the load is not good, the body always speaks. In 2015, when I was working full-time at Dell and at the same time I was trying to launch a startup and study at the Open University. The load was unreasonable, and I developed Crohn's disease. So I stopped my degree studies in the middle, even if my grades were high, because with all my military service and the work experience I gained in various places, I could manage.

"In contrast, in 2021, when I suffered a herniated disc in my neck, I continued to talk to potential clients while hospitalized, even though I couldn't move my arm. The doctors complained that they felt like they were entering my office. "

Why didn't you raise capital, like everyone else?

"I thought we would make an exit in two years like everyone else, but things turned around and we added more and more clients. At the beginning, when I heard about friends going to funds to raise money, I also wanted to, but during one of the presentations in front of the investor, the person started to change the whole product for me and said: 'Change a few things and come back to me.'

And today?

"We have cash in the bank and we are profitable, so I am in no rush to raise money. If a strong investor comes along who can help us increase our competitive advantage, increase the marketing and sales budget for a more extensive penetration of the market - we would want that. But I'm not going to go on a fundraising spree now."

Bootstrapped companies get a lot of respect from the industry, but the disadvantage is that you do not have a VC that wants to maximize its investment and help you record an exit.

"That's right. We already understood that if we continue to operate alone, our value will not be very high, that's why we reorganized, brought in a CFO, and we are working hard on business and technological collaborations. These are things that increase value, and will advance the company to an exit or an IPO further down the road."

Aren't you a company that’s "too old" to exit?

"It crossed my mind after so much time without investment, but the momentum has been renewed thanks to the collaborations we will launch, the significant marketing we will start doing and the new customers we will recruit this year. So I don't see the exit as a station that the train has passed by, but as a station that it has not yet reached."

Is the cyber field in Israel not saturated in your opinion?

"There are endless niches in the field, which is why there are so many companies. Companies like CrowdStrike or Wiz try to offer everything under one umbrella, so that you don't have to buy 100 different products that cover everything, and it seems that's where companies are going today."

Is the cyber industry sexist? There are few women entrepreneurs in the field.

"Women are not afraid of work. The problem is that when the children are young, most of the responsibility falls on the mother, so women find themselves blocked between their late 20s and 30 plus. Only when they pass that age range do they know how to fight back. That's why up to a certain point you find many women in the position of vice president and not CEO."

Have you encountered discrimination?

"I was met with disdain, until I opened my mouth. I've also heard of women who feel discriminated against, but in my eyes, being the only girl in the room is also an advantage, you get noticed."