"The genome project will change the face of medicine in Israel and save human lives"

Psifas is an ambitious new genome project aiming to create a genetic database of Israel’s citizens, with a budget of NIS 250 million. The collected information already provides information that will make it possible to treat life-threatening diseases in the subjects. The hope is that after accumulating 100,000 samples, the database will help jumpstart the biotech industry. CEO Prof. Gabi Barbash: "Psifas is a great achievement and advantage for Israel, which aspires to become a global hub of biotechnological information."

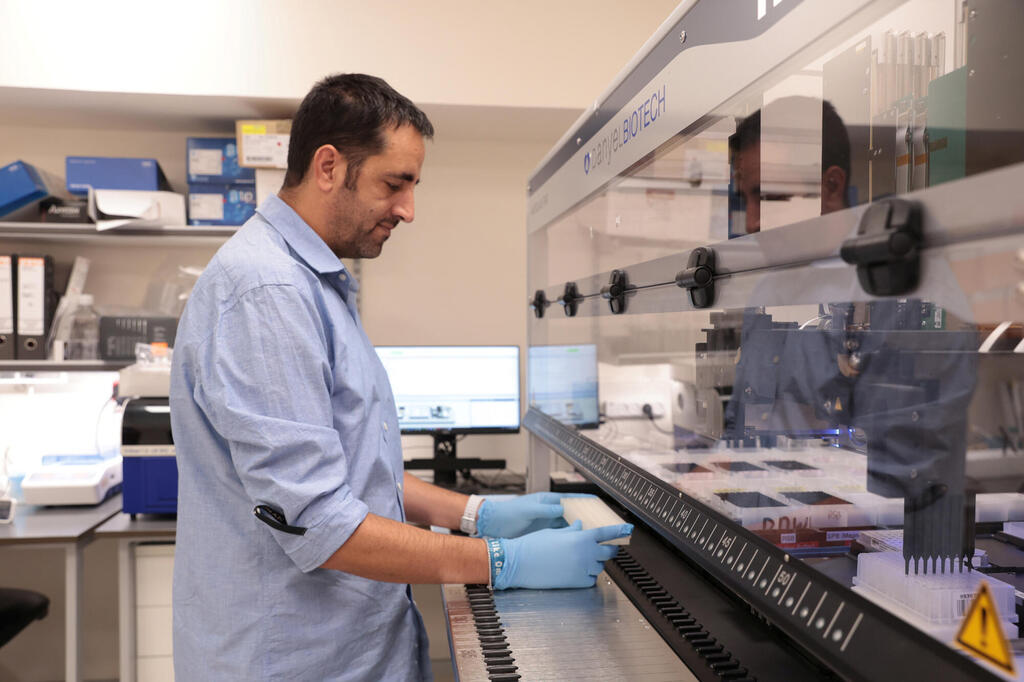

In a small room on the tenth floor of the Sourasky Building at Ichilov Hospital, one of the most ambitious projects in Israel’s healthcare system is underway: the "Psifas" project, also known as the Israeli Genome Project. Revealed here for the first time, the project aims to create a national clinical genetic database based on samples from 100,000 Israelis. Blood samples collected from volunteers at a station in the hospital lobby are taken to Ziv Itach Abramovitch, the core facility manager at the hospital, where they undergo a series of processes in robotic machines to extract DNA. The DNA is then stored in a freezer at minus 20 degrees before being transferred to another machine, which completes a genetic sequencing process for up to 128 samples at a time within 48 hours, sending the results for further analysis. The project's goal, as announced during its launch at the President’s residence last year, is to "change the world of Israeli medicine." Accordingly, it has been allocated a budget of 250 million shekels.

The project is a collaborative effort among various hospitals, with Clalit, Israel's largest HMO, as a major partner. Currently, only Clalit members are eligible to participate in the project and volunteer at designated centers in hospitals across the country. The sequencing center established at Rabin Medical Center is the largest and most advanced in Israel, enabling tens of thousands of genomic sequences per year for Clalit members.

"We joined the leadership of this important national project from the day it was established to provide our members with the most advanced healthcare available—proactive, preventive, and personalized," says Prof. Ran Balicer, Chief Innovation Officer and Deputy Director-General at Clalit Health Services. Prof. Shay Ben Shachar, Head of Precision Medicine at Clalit, adds, "Approximately 4% of Psifas volunteers already receive personalized genomic counseling, allowing them to prevent or reduce the chances of developing serious illnesses with guidance from experts at Israel's leading genomic center."

Creating a unique Israeli genetic database is crucial for several reasons. As a diverse, immigrant-based society, Israel encompasses a wide array of genetic characteristics. Each group and origin may have unique genetic traits, with specific studies underway on populations such as those with both parents born in Iraq or Turkey, for example. There is also an economic benefit: data collected from Psifas samples will be available to local research institutions and industry at a subsidized rate.

Samples for the project are collected at other hospitals as well, with the aim of making this vast Israeli database accessible to researchers both locally and globally. Prof. Gabi Barbash, CEO of Psifas and former CEO of Ichilov Hospital and the Ministry of Health, explains, “Similar projects exist worldwide, but we believe we have distinct advantages, including our population’s diversity and accessibility to clinical data, as evidenced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Researchers using this database can uncover valuable insights.”

These insights include identifying genetic and molecular risk factors for diseases, developing new drugs, examining the effects of existing drugs on various population groups, and personalizing treatments or dosage levels. Additionally, the database supports long-term studies on large populations. "Think of it as academic infrastructure," Barbash describes. "This is a foundational resource that everyone can benefit from, enhancing biotechnological and medical research in Israel and advancing both medicine and industry. Start-ups will have access to this data, eliminating the need to approach individual HMOs and hospitals, as everything is accessible and ready at a subsidized price."

According to Barbash, "Without the involvement of the Ministry of Health and Moshe Bar Siman Tov during his tenure as CEO of the Ministry eight years ago, and without the support of a budget division within the Treasury that recognized the importance of national biotechnological infrastructure, this project would not have materialized. Today, it is supported by the Planning and Budgeting Committee, the Innovation Authority, and the National Digital Agency."

Some insights from the database offer immediate and life-saving potential. One incentive for volunteers is that after DNA sequencing, they will receive the analysis results. If one of the 80 Actionable Genes (AG) associated with heart disease or cancer is detected and validated, they will be notified and can take preventive measures. "This, in a way, is our thank-you to the people who provided both their blood and consent to access their data,” Barbash says. “These are actionable genes where something can be done.”

What for example?

"There are, for example, genes that indicate heart rhythm disturbances. If detected, a person may be given a pacemaker to prevent sudden issues. Think of the tragic story of a young man who, at 20, suddenly collapses and dies. When you investigate his family history, you may discover a genetic predisposition to arrhythmia."

Positive response from Israeli participants

The project officially launched on January 10, 2023, with the first sample taken from Dr. Avi Gadoth of Ichilov Hospital. Today, nearly two years later, samples have already been collected from close to 50,000 Israelis, with minimal publicity. "The Israeli public has responded positively and is cooperating fully," says Barbash. Currently, only members of Clalit Health Services can participate. However, this limited access underscores the project’s potential. Although the project is only halfway to its sampling goal, it has already prompted initial studies targeting patient groups to investigate potential genetic links to their conditions. Patients from other HMOs can also donate samples if they are invited to participate in these specialized studies. "About 50% of our population has diseases that have not yet been adequately addressed," says Barbash. "Researchers from various hospitals will be able to pose interesting questions about the genetic basis of these diseases and find answers using the database."

An example of such research comes from Dr. Ari Raphael, a clinical oncology specialist at Ichilov Hospital, who oversees the "young oncology database." In just a month and a half, this initiative has collected 35 samples. "These are serious and life-threatening diseases, but we often don’t detect the genomic change responsible, nor understand why the tumor developed," he says. "For instance, we’re seeing cancers like digestive system, colon, stomach, breast, and gynecological tumors occurring at younger ages, but we don’t fully understand why. Having a young oncology database is therefore critical."

What does it include?

"The database includes individuals diagnosed with cancer between the ages of 18 and 40. Beyond genetic information, it encompasses comprehensive clinical data. We use detailed questionnaires that gather information on the specific type and stage of cancer, the organs affected, and the treatments administered. This data has enormous potential for future research, helping us identify common factors among patients. If a genetic change is found, it would be fascinating to investigate if it appears in other family members as well.

"Currently, genetic testing isn’t routine for many types of cancer patients, aside from breast and ovarian cancers, which typically include genetic sequencing. For other tumors, genetic testing often isn’t covered, making this Psifas database invaluable by offering high-quality, whole-genome sequencing using Illumina technology to analyze genetic variation and biological function. Genetic changes are assessed against the gene list defined by the American College of Genetics, the most reputable source in this field."

"Quick ability to recruit patients"

The benefits of this resource for Israel’s biotech industry are substantial. Dr. Liran Shlush, a physician and researcher in the Department of Immunology at the Weizmann Institute, has been working for about three years to develop a simple test to replace bone marrow tests, which are essential for diagnosing many blood cancers. The Psifas project is expected to play a key role in advancing this effort, especially in terms of procedural efficiency. "Each year, about a million bone marrow tests are performed globally, each costing around $3,000. We are developing a simple, affordable blood test that bypasses the need for pathology,” he says. “Psifas is a crucial part of that.”

What are the limitations of the current test?

"It’s a highly unpleasant procedure that involves smearing and taking a biopsy directly from the bone. It’s also an expensive process requiring multiple professionals—from those who perform the biopsy to those who analyze it. Dr. Amos Tanay, another scientist here at the institute, and I, along with my students, have developed a method that could replace this invasive test with a simple blood draw. We conducted a preliminary study with 100 participants at the Weizmann Institute, which concluded a year ago. To validate our blood test, we need a large group of people who are undergoing a bone marrow test and from whom we can take a blood sample on the same day. Through Psifas, we’ll have access to 600 participants, and they’re helping coordinate the effort across the organization.”

How does Psifas assist the project?

"Psifas operates in hospitals and has streamlined the process of recruiting patients, quickly obtaining necessary approvals from ethics committees for this type of research. They conduct the study according to clinical research standards, ensuring that it meets the requirements for eventual FDA submission. In Israel, we often struggle to scale a promising idea into a large company. Psifas helps bridge that gap, taking our concept and organizing it into a clinical study that will monitor patients over a three-year period. Psifas has a team that follows all patients and performs comprehensive genomic sequencing for them, providing us with an additional dataset that complements our work."

How much time does this save?

"On our own, this would have taken us years. We’re now establishing a company, Cliseq, and when we speak to investors, the progress we’ve made with Psifas is a game-changer. Academia often excels at generating ideas, but turning these into clinical research is challenging. Psifas makes this possible."

So, Psifas provides an infrastructure that jumpstarts and advances research?

"Exactly. Especially in diagnostics, it enables the development of new tests that could transform current practices. Psifas removes significant barriers. Without them, I’d have to approach multiple hospitals, handle ethical approvals, and hire research assistants to recruit patients—tasks that would be nearly impossible to manage. Psifas offers this infrastructure at a relatively low, subsidized cost. We’re trying to run a similar study internationally, and with Psifas, the time was reduced by about 90% and costs were significantly lower. This gives Israel an edge in biotech. Soon, for example, the Weizmann Institute will open a medical school, and we plan to use Psifas as a teaching tool, allowing students to study genetics through Israel’s diverse population database."

"Strict protection of privacy"

When asked about his insights from similar projects around the world and why it’s worthwhile for Israel to invest in this initiative, Prof. Barbash responded: “First, there’s the unique diversity of the population in Israel; second, the accessibility to high-quality clinical information that doesn’t exist elsewhere; and third, our ability to reach patients, which we leverage. For example, companies approach us saying, ‘We need you to recruit a specific population that interests us. You already have agreements in place; please recruit these patients because they are crucial to our research.’ There are already two such projects in progress. This collaboration will benefit both the company and Psifas because, ultimately, the data collected on these patients will be available for broader research.”

Are there any unique challenges in Israel compared to similar projects elsewhere?

“Until now, funding has been the main challenge. If you look at genetic repositories in other countries, like the UK BioBank, the government contributes maybe 15-20% of the budget, while a philanthropic foundation like the Wellcome Trust funds 70-80% of the project. With Psifas, there’s a great achievement and advantage for Israel, which aspires to become a global hub of biotechnological information.”

What about privacy protection?

“I don’t want to tempt hackers, but we’ve created a highly decentralized and secure system. The clinical data are stored separately and are fully anonymized, with no link to where the volunteers’ identifying information is kept—these are entirely different systems.”

Can you explain this in more detail?

“There are multiple layers of data encryption. The data stored in Psifas’s system is separated by clinical and demographic categories, and patient names are not identified. We’ve removed identifying details, such as names, ID numbers, and addresses, and adjusted visit dates in the system. So, for example, if someone knew a person visited the ER, they wouldn’t be able to trace them back through this system.

"The next step involves a researcher applying for approval from the Helsinki Committee to access the database. We then prepare a dataset that matches the criteria they specified. The researcher receives this data, but only as processed, anonymous information; even the Psifas ID numbers are removed. If the researcher finds something rare and wants to follow up, it’s impossible because the information is fully anonymized. However, we maintain a conversion table that links Psifas IDs to the original patient data, so if actionable genetic findings arise, we can reach out to those individuals directly. But outside of that, the researcher has no way to trace individuals, ensuring complete privacy."