Analysis

Can Selina and WeWork find stability beyond the high-tech mirage?

Shaping the future: Pondering Selina and WeWork's path to stability beyond high-tech illusions

What is the actual value of hospitality company Selina? How much is co-working space company WeWork genuinely worth? Nobody truly knows, but it is evident that the valuations of $1.2 billion and $48 billion, respectively, at which the two companies were once valued, are far from accurate.

However, the present valuation levels at which these two companies, sharing several similarities, are traded, are also currently unreliable. WeWork has a market cap of around $100 million, while Selina is valued at about $50 million, a valuation it reached after plummeting by 41% last Friday.

1 View gallery

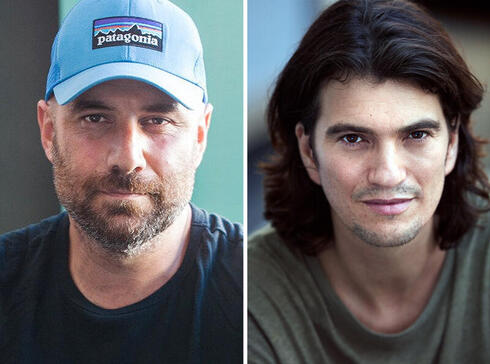

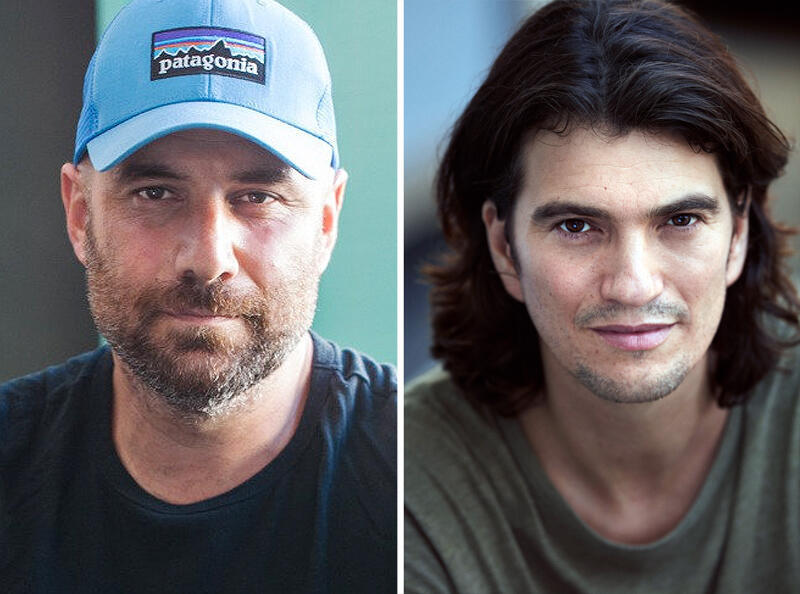

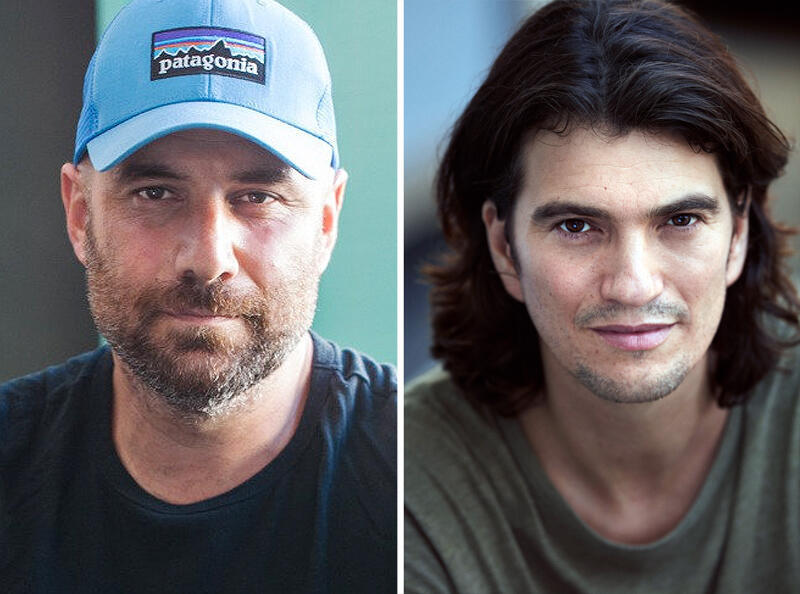

Adam Neumann (right) and Selina co-founder Daniel Rudasevski.

(Photo: Alexei Hai, Selina)

The weekend witnessed significant attention towards Selina's steep dive and endeavors to scrutinize the situation and the resultant new market valuation. Yet, these efforts prove futile. This nosedive is a technical consequence of an impending flood of shares hitting the market and is not directly indicative of Selina's business standing. In comparison to the $1.2 billion valuation from less than a year ago, a 93% loss and a 96% loss hold little distinction. Investors who entered at the peak suffered substantial losses in both cases. However, it's imperative to focus on the present downturn and its potential lessons.

Beyond the shared detail that Adam Neumann, the ousted founder of WeWork, was an early investor in Selina, these two companies have more in common: they are not authentic technology companies. This harbors both negative and positive implications.

On a positive note, in contrast to numerous high-tech firms that surfaced during the bubble years of 2021, valued at billions, both Selina and WeWork possess tangible, existing markets, actual paying customers, and discernible assets. The market valuation of these companies fails to reflect the occupancy rates of their co-working spaces or hotels. Anyone stepping into a WeWork location in Tel Aviv, New York, or London would witness a bustling crowd. Likewise, the same holds true for vacationers at Selina's sites in the Sea of Galilee or at its other 117 destinations.

Although this may appear somewhat insufficient, it is a whole lot more than what many technology companies, both private and publicly traded, striving in domains such as autonomous vehicles, food tech, or biotechnology, can offer. These companies lack paying customers, revenue streams, and occasionally have unfinished products. Their valuation hinges solely on an aspiration and the associated enthusiasm.

The downside lies in the flawed business model of both Selina and WeWork. The root of this issue is that both firms are managed akin to high-tech companies—fueled by vision and dreams—rather than operational entities, which is their true nature. Profit can indeed arise from co-working spaces and youth-oriented, branded hotels tailored to preferences. Yet, these seemingly mundane ventures are intricate and resource-intensive, necessitating meticulous scrutiny of every facet. Managing such ventures often exceeds the capacities of investors accustomed to the high-tech pace and entrepreneurs conceiving high-tech-like concepts.

Both Selina and WeWork direly require pragmatic managers capable of rescuing them from undue expectations and appreciating their essence—real estate companies where success versus failure hinges on financing, utility costs, and even the expenses of a disposable lobby cup. A world apart from the high-tech realm.

Recent weeks have seen WeWork receive a "going concern" note, and Selina declared strategic measures a few months ago to safeguard its future—actions encompassing massive layoffs and site closures. Yet, neither entity has undergone substantial transformation to shed the inadvertent "high-tech" layer ingrained in their DNA. For this shift to materialize, they must become private companies once more and transfer control to real estate and hospitality professionals.

Only through an extended phase in which the companies shed their past, and after the public forgets their high-tech association, can a genuine reassessment of their value transpire.