Too soon? Jewish-American comedians use humor to cope post October 7

Jewish stand-up comedians in America are turning the growing anti-Semitism since October 7 into the hottest material in their shows. Because for 2,000 years, from Haman, to the Nazis, to the anti-Israel progressives at Harvard, humor has been the best defense.

“When the pandemic started, I performed a live benefit show for United Hatzalah,” Israeli-American comedian Modi says during his stand-up routine. “This is an organization of Jewish ambulances. We need them because no one else will come to take us. The truth is that you can't tell if these are really ambulances, because everyone who donated 18 dollars gets their name on the vehicle. It's like a wall at Yad Vashem. And when you call them, before you even hang up, 12 men arrive, two take care of the patient and ten give you a price estimate on your house.”

On October 7, Modi Rosenfeld, an actor and very successful standup comedian, was in Israel. "We finished a week of sold-out performances throughout the holiday of Sukkot," says Rosenfeld (53), known by most simply by his stage name, Modi. "Leo, my husband and I were in a hotel in Jaffa and we were supposed to fly to Paris on Saturday night. We went to bed late but woke up early in the morning, and like everyone else we realized that something terrible was happening. We managed to leave Israel on the very last flight in the evening. Two days later I did a show in Paris."

Didn't you think about canceling the show?

"No. Humor is the only way I know to deal with the greatest pain. For the first time after 48 hours I put the phone aside and went on stage. With a heavy heart, but I still went up, and since then I haven't stopped performing."

These experiences have already become the stuff of jokes that Modi has used ever since. For example: "Bruno Mars was in our hotel in Jaffa on October 7, and we saw them smuggle him out on a private plane to rescue him from Israel. I told Leo: 'Thank God they took him out, otherwise if a bomb were to fall on this hotel now and he and I die, I’d get zero media attention." Or: "In the middle of a performance, someone shouted at me: 'If Israel needs you to go fight, will you go fight?'. I told him that if there is a discussion in the IDF where someone says 'We need Modi,' that means Israel has already lost."

Isn't there some minimum period of time that must pass before you can laugh after a great tragedy?

"It's individual, but I move very quickly to laughing, I think as a Jew I have no choice."

Has anything changed in your performances?

"I end the performance by singing 'Hatikva', but apart from that I do what I did before October 7: I make fun of anti-Semitism. I don't talk much about the war itself, but I do laugh at the stupid anti-Semitism it revealed. In the end, I want to give the audience an hour and a half of relief and also a feeling that we are not alone. I have a relative who is a Holocaust survivor who survived all the biggest extermination camps, and he is not at all moved by what is happening. He says that this is simply a new season of the Holocaust."

"Jokes are a way to deal with a crappy world"

"If you're Jewish only on your father's side, some Jews think you're Jewish enough for Germany but not for Israel. When a liberal Jew tells you he's 'conservative', he means they eat Shabbat dinner"- Gianmarco Soresi

Maybe the Jews really have no choice but to quickly switch to laughing. At least the comedians themselves don't really believe in a cooling off period. Gilbert Gottfried, for example, was one of the most extreme comedians in America. No joke seemed excessive to him. Two and a half weeks after 9/11, with clouds of dust still rising from Ground Zero, Gottfried took the stage at a stand-up club in New York and said: "I have to catch a flight to California. I can’t get a direct flight. They said they have to stop at the Empire State Building first." The gasps by some of the audience was stronger than the boos that came from the others. Gottfried decided that it couldn't get any worse, and switched to a joke about pedophilia and incest. The audience recovered, and laughed. "Comedy is something we invented to have a way to deal with how messed up the world is," Gottfried later explained. "People are hurt by a joke about something that happened recently or something that happened to them, but they have no problem laughing about pedophilia and incest."

Gottfried died two years ago at the age of 67, but left behind this story, which has become a myth. Mainly because almost 23 years after those attacks, American comedians are still afraid to touch September 11. As Mark Twain once said (or maybe it was Carol Burnett, no one knows for sure)? "Tragedy plus time equals comedy." The question that always remains open is what the tragedy is - and how much time has passed.

Eddie Portnoy and Ben Kaplan, two of the world's leading researchers of Jewish humor, who long before October 7 planned a comprehensive online course on the subject, also wrestled with the answer to this question. They called it "Is Anything Okay?" and gathered a host of well-known comedians as guest speakers — including Modi, Paul Reiser, Marc Maron, Lewis Black, Jena Friedman and more — and intended to go live in November. "We worked on it for several years, and we were already at the end of the preparations," Portnoy told Calcalist. "We scheduled a meeting for October 9. Not only did we cancel it, but we also realized that the course had to be postponed. We literally said to each other: 'We can't talk about Jewish humor and laughter right now.'"

This course goes live this week, but in the six months that have passed since October 7, the Jews in the stand-up clubs in New York and Los Angeles have proven that it may not be possible to talk about Jewish humor, but it is possible to do Jewish humor. Like all their predecessors in the field - who were actually the founding fathers of American comedy, we'll get to that later - they simply deal with the general anxiety, and with the specific anxiety, the one that touches their lives, the one they didn't know before, in the safe Jewish-American comfort in which they grew up. Yes, anti-Semitism is currently the hottest spur to the good old American humor.

Here is an example from the show of Gianmarco Soresi (35): "After October 7 was the first time that my black friends looked nervous before they talked to me... I have an Israeli barber, I went to him to straighten my beard and he asked what I thought about the Israel-Palestine conflict. I noticed that the closer his razor got to my neck, the more pro-Israel I became... The problem is that even if I want to criticize Israel, there are real anti-Semites out there, that's a fact. People complain so much about Jews, do you know how they sound? They sound like Jews... They say 'the Jews run the banks'. Okay, so take your money out of the bank. It never happens because they don't trust the cops to guard their money. Do you know why? Because the Jews don't run the police. We would be happy to run the police, but we keep kosher. I love this joke because the people who are supposed to be hurt by it don't understand it at all."

"Humor that always stands in the shadow of Holocaust jokes"

"I grew up in Crown Heights in Brooklyn. We were ten children. I grew up poor, and I don't understand how it is possible to be born Jewish and poor today, it hasn't happened since Anne Frank." - Robby Hoffman

From the perspective of the researcher, Kaplan listens to Soresi and others and says: "A straight line runs between Yiddish humor that responds to the oppression of the Russian Empire in the 19th century and comedians on TikTok today. What has changed is the content, the technology, the format, but the basis of using comedy to digest fears and threats remains the same." And Portnoy summarizes: "Anti-Semitism is a constant element in the world, and so is comedy as a Jewish response to it."

Are the Jewish comedians currently dealing with their Judaism more than before?

"To a certain extent. It's a completely natural reaction in days of great anxiety and a rise in anti-Semitism, to look inside to deal with what's happening outside - but that's what Jewish comedians have always done. But we do see a change in the way Americans relate to their Jewish identity, they think more deeply about what it means now to be Jewish, so of course it also happens with comedians, who use their own way to gain some intellectual control over their vulnerability. Lewis Black, one of the funniest Jews out there, says that Jews laugh at themselves because we want to get ahead of others before they laugh at us. We've turned self-loathing into an art form, there's nothing anyone can say about me that I haven't already said about myself. It's the power of fighting back, but it's also the exhausting difficulty of a never-ending war with this constant oppression."

Portnoy: "Jews invented psychiatry. We think about ourselves all the time, and comedy is another way to do that. Most of the comedians in America until the sixties were Jewish, but they told jokes, they didn't make Judaism the center of their comedy. Then came Lenny Bruce followed by Woody Allen and started telling personal stories. Today's young people continue this: identity is the basis of their comedy, and when your identity is Jewish - you have a lot of material."

How far can you go in such a time? How dark can the humor be?

Portnoy: "Every such question is always overshadowed by jokes from the Holocaust. People told jokes back then that were at the edge of the dark, and they were the furthest marker, so there is quite a bit of a margin."

Give an example of such a joke.

Portnoy: "A Jew is walking down the street in Berlin and runs into Hitler. Hitler pulls out a gun and says to him, 'Jew, do you see the dog's shit on the sidewalk? Eat it!' The Jew bends down and begins to eat. Hitler laughs so hard that the gun falls from his hand. The Jew takes control of the gun, points it at Hitler and tells him, 'Now you will eat the dog's shit'. Hitler starts eating and the Jew runs away. He comes home and says to his wife, 'You won't believe who I had lunch with today.'"

It's a joke that gives us victory.

Portnoy: "Exactly, that's what jokes in the Jewish context do. They give us a certain control over the situation. It allows a Jew to beat Hitler."

Decades before "Inglourious Basterds".

Portnoy: "Only this is not a Hollywood fantasy but a joke that people really told in the Holocaust."

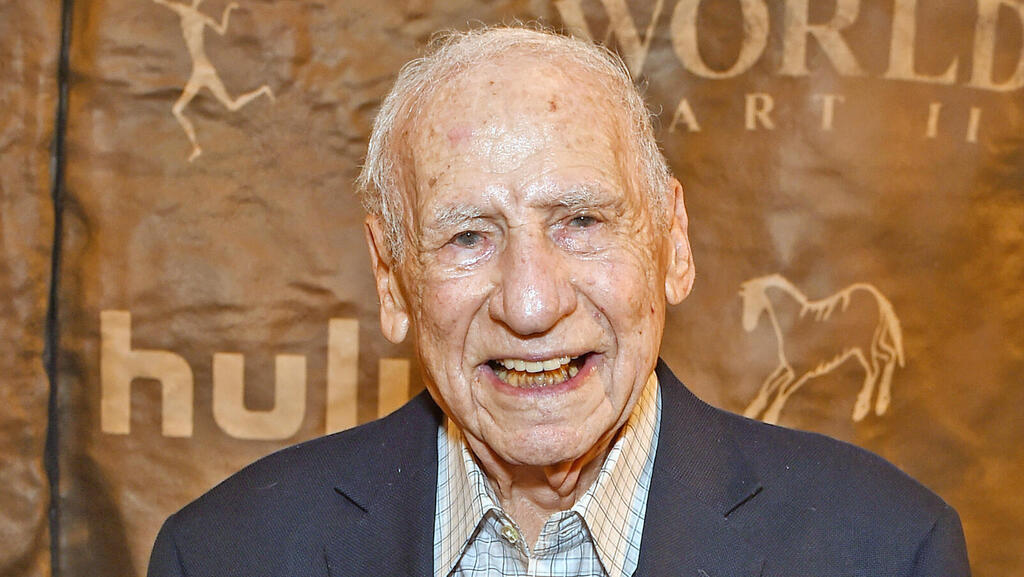

Kaplan: "Mel Brooks always makes the distinction between Nazi jokes and Holocaust jokes, and that makes it easier to digest."

And what is the difference?

Portnoy: "When the movie 'The Producers' came out in 1968, almost 25 years after the Holocaust, many people were hurt, but Brooks put on a Hitler mustache and told jokes already in 1950. 'The Producers' is so successful because it laughs at the Nazis, it doesn't laugh about the Jew who suffered from the Nazis."

Kaplan: "Comedian Judy Gold asks, 'If I stood naked in line for the showers at the camps, would I pull in my stomach?' She works in a much more modern context, which is part of the genius of Jewish humor. There is nothing we haven't been through, and everything we've been through can be a reference to something else in the world."

"The Jews were the incubator of all American comedy"

"It's complicated to be both black and Jewish, because blacks sometimes say anti-Semitic things, but it's by mistake. The point is that all the stereotypes against blacks are negative: 'You don't take care of children,' 'You kill each other,' 'You sell drugs.' But when you compliment the Jews and say 'You are good at business' — 'Oh no, that's hate speech!'" - Eagle Witt

Portnoy (63) has a doctorate in modern Jewish history from the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York and a master's degree in Yiddish studies from Columbia University. He is a consultant to the Museum of the City of New York, the Museum of Art and Jewish History in Paris and the Museum of Jewish History in Amsterdam, and the author of the book "Bad Rabbi: And Other Strange but True Stories from the Yiddish Press". Kaplan (35) studied literature and theater at the prestigious Williams College in Massachusetts, wrote an opera about Herzl, speaks Yiddish and is a senior at the YIVO Institute, which has been engaged in the preservation and research of Jewish history and culture for nearly a century and owns one of the world's largest archives on the subject. Kaplan and Portnoy aim their new course at YIVO at a diverse population, understanding that in the case of humor, our history and culture go far beyond the Jewish world alone. Basically, Jewish history built American humor.

How did it happen that we Jews actually gave birth to comedy in the United States? Are we funnier than others?

Portnoy: "No, it came from the same constraints of persecution and oppression. There were many professions in which Jews found it difficult to integrate, so they were willing to take a risk and become comedians - there was a time, towards the middle of the 20th century, when 75% of the comedians in America were Jewish. And resorts were closed to Jews. This is how the concept of vacations in the Catskill Mountains, north of New York City, was born and there grew hotels and resorts where almost every comedian, Jewish or not, appeared. It was the incubator of all American comedy."

Is it possible in all this to define the characteristics of Jewish humor that shaped American humor?

"I would say that the unique characteristics of comedy that Jewish artists have contributed are the introspective and neurotic storytelling style, and the snark. In addition, Lenny Bruce's impact on comedy is immeasurable. His battles over foul language and provocative content changed all of comedy forever."

But even this comedy has already changed. As an oppressed minority are we still allowed to laugh at other minorities?

"No one is allowed to laugh at nationalities or religions or races anymore. A hundred years ago all comedy consisted of laughing at others, it was offensive, but you laughed at yourself too. Today even self-humor has limits. This is the historical point we are in, but it doesn't mean it will stay that way."

Kaplan: "Joan Rivers and Lenny Bruce tested the limits 60 years ago. Lenny Bruce was arrested and tried because he said things that today people write on the Internet (Bruce was arrested several times and prosecuted for using obscene language, among other things because he said cocksucker and shmuck). What was funny even just five years ago doesn't work now. This is not a new phenomenon, humor always adjusts according to society. It's also a way to examine history because you can look at a joke at a certain moment and understand a lot about the social norms of that time."

Portnoy: "I was teaching a course on Jewish humor at Rutgers University and I showed the students clips of Lenny Bruce. Not only did they think it was shocking and unbearable, they also didn't think it was funny. I explained to them its place in the history of comedy, but they just couldn't get out of the moment and understand how funny it was in his time."

Kaplan: "Technology has a huge impact. Comedians used to go to clubs and test their material there. It was a safe place, they could take risks and say anything without fear of being canceled. Now comedians go to the club, everyone has a smartphone and they have to be much more careful. It's sad because everyone wants to make a viral clip, so obviously you're much more careful—and that affects the comedy you can create."

Could Lenny Bruce, Joan Rivers or Gilbert Gottfried even make it today?

Portnoy: "The really good comedians can adapt to any era and remain funny. Sarah Silverman, for example, is so good that she would have been successful in any era."

Do you have red lines, subjects you won’t joke about?

"My red line is unfunny comedy."

Are there non-Jewish comedians with Jewish humor?

Portnoy: "Robin Williams is the obvious answer. He had Jewish sensitivity and vulnerability and neuroticism."

Kaplan: "If someone is really good, Jews will say he is a Jewish comedian."

Portnoy: "Comedy is generally passed off as a Jewish industry, so everyone involved in it sounds a bit Jewish. But I think you can still tell who is Jewish and who isn't. Those who rejected 'Seinfeld' at first were Jewish producers, because they were worried that it would be too Jewish a series in the country in which Jews are a very small minority (but most of those who produced it in the end were also Jews). The series does not deal with Judaism directly, they even made the Costanza family Italian - although they have nothing to do with Italians and it is clear that it is a completely Jewish family - but Jews see Seinfeld as a Jewish series, and everyone else sees it as just a funny series."

And where will Jewish humor go after October 7?

Kaplan: "In the United States there are many, many different identities and many, many people who deal with the questions of what it means to be American, and how much of my culture and identity I have to give up in order to get an entrance ticket to the project that is America. Part of the anxiety of Jews in the middle of the 20th century was related to their integration in this project, and I think now we see that anxiety returning. It's too early to know where it will go, half a year after such a massive event like October 7 is not enough time from a historical point of view, but I feel the change in my environment, and it is always reflected in the end as well in what we see from Jewish comedians."

Modi Rosenfeld makes a sharper distinction within this comic world. "There is a difference between Jewish comedians and Jews who are comedians," he says. "I'm a Jewish comedian, that's my story, whoever comes to my show knows that's what they're going to get. Jerry Seinfeld is a Jew who's also a comedian. It's not the same thing."

If so, is it more difficult or scary for you to perform now?

"It's not more difficult, even if here and there at concerts in Europe it's a little scary, but certainly more significant. Sometimes I have to explain to people in the audience what anti-Semitism is, and then I say it's hating Jews more than is allowed."