Intel’s Hail Mary play: Will a foundry split and AWS deal revive the giant?

Facing competition from Nvidia and a $10B cost-cutting plan, Intel takes dramatic steps to stay in the game.

In American football terminology, there is a well-known term called the "Hail Mary pass." Towards the end of a game, when all other options are exhausted, a player may throw a long pass toward the other end of the field, hoping a teammate will catch it for a touchdown, turning the game around at the last moment.

The series of moves announced by Intel on Monday—spinning off its chip manufacturing division, halting plans to establish factories, and reducing its global real estate by two-thirds—comes in addition to the significant cutbacks and layoffs the company revealed a month and a half ago. Together, these steps resemble a "Hail Mary pass" aimed at stopping Intel's rapid decline and potentially allowing it to return to a path of growth and prosperity.

This could have been Intel's heyday. But the last two years—the era of generative artificial intelligence (GenAI)—have perhaps been the most challenging in Intel's history. Global demand for chips is at an all-time high, driven by an insatiable need for high-performance AI chips. This has deepened the global chip shortage, which began due to disruptions caused by the COVID-19 pandemic. But Intel has not benefitted from this surge in demand, which has largely gone to Nvidia. The result: Nvidia’s stock has soared, making it one of the world's most valuable companies, while Intel's revenues have plummeted, profits have turned to losses, and the company now faces an existential crisis.

For a company that missed one major revolution (smartphones) and a significant market trend (the rise of companies developing their own chips and outsourcing production), missing the AI revolution could be catastrophic. To avoid this, Intel requires a fundamental change in strategy and bold action. The first phase came in August when the company announced a $10 billion cost-cutting plan, which included laying off 15,000 employees—15% of its workforce—and more targeted measures like canceling leasing programs and reducing employee benefits.

Monday brought the second phase. The most significant move: transforming the foundry division—Intel's business of manufacturing chips for other companies—into a fully controlled subsidiary. This move addresses a market trend that Intel missed, a trend that has allowed companies like Taiwan’s TSMC to become key players in the global economy.

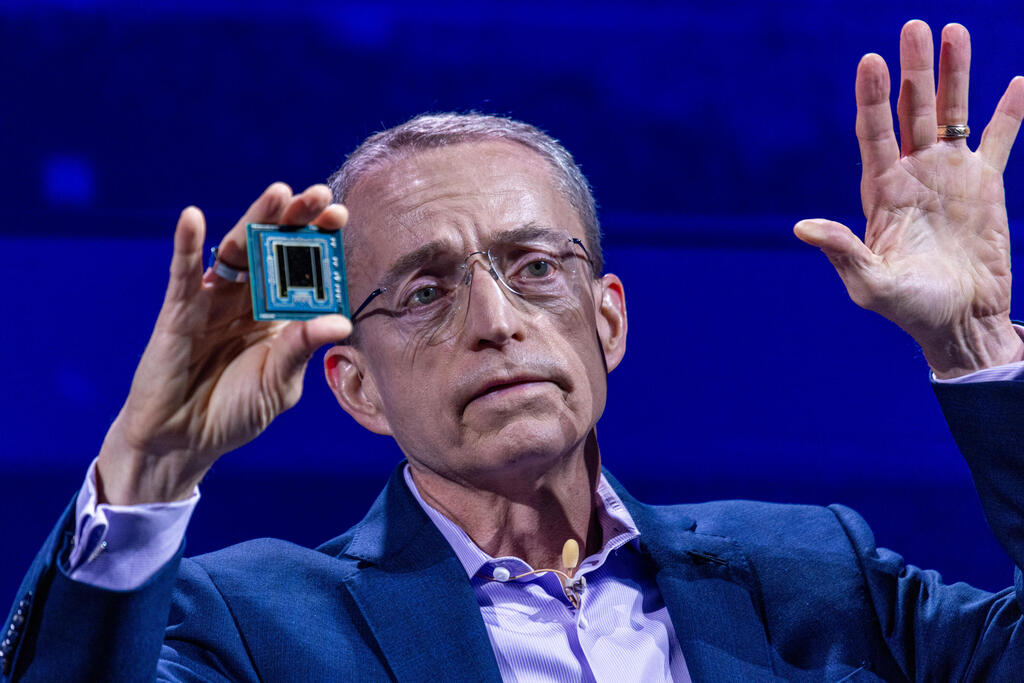

Historically, Intel only produced chips based on its own designs under its own branding, a strategy that worked well until the smartphone revolution. Companies like Qualcomm quickly adapted, making chips for mobile devices, while firms like Apple moved to develop their own chips. When Pat Gelsinger became Intel's CEO three years ago, creating a foundry business was central to his strategy to bring Intel back into the limelight. It was a high-stakes gamble—foundry operations require building new, expensive factories at costs of tens of billions of dollars, with production ramping up only years later. However, the potential profitability was substantial.

Intel, bolstered by government grants and investments, began building a series of new factories in the U.S., Europe, and Israel. But the foundry business has yet to take off, Intel's financial situation has deteriorated, and potential customers are hesitant to hand over their designs to a company that is also a competitor.

The move to split off the foundry business into a subsidiary is intended to address these concerns. Greater independence for the foundry operation could ease customer worries and align Intel with industry norms, where most foundry companies do not have in-house chip design operations. More importantly, this structure will allow the new subsidiary to raise capital independently, giving Intel access to the resources needed to ramp up the foundry business while maintaining control over its core activities—namely, developing Intel’s own chips.

"A subsidiary structure will unlock important benefits. It provides our external foundry customers and suppliers with clearer separation and independence from the rest of Intel. Importantly, it also gives us future flexibility to evaluate independent sources of funding and optimize the capital structure of each business to maximize growth and shareholder value creation," Gelsinger wrote in a letter to employees. For potential investors, this means the opportunity to invest in a single, promising business rather than a massive corporation with many challenges, such as its weak presence in the mobile chip market and its inability to compete with Nvidia’s AI chips.

While the move could be a precursor to spinning off or selling the foundry business, Gelsinger stated that Intel does not currently plan to do so, believing the company is better off as a single entity.

Along with the foundry split, Intel also announced further cutbacks, including delaying plans to build factories in Poland and Germany for two years and putting construction of a facility in Malaysia on hold until demand increases. Additionally, Intel plans to reduce its global real estate by two-thirds by year’s end, focusing on consolidating small and isolated teams to improve efficiency.

Intel is also expected to sell its stake in programmable logic devices (PLDs) manufacturer Altera, "which is something we have talked about publicly several times and has long been part of our strategy to generate proceeds for Intel on Altera’s path to an IPO," Gelsinger wrote.

One question remains: how will these moves affect Intel's extensive operations in Israel, which include major R&D centers, large factories, and a new facility under construction in Kiryat Gat? Intel’s announcement did not directly mention Israel, but it is likely the impact will be limited. Gelsinger clarified that the company has no plans to alter its other production locations. Intel's Israeli R&D offices, primarily in Haifa, are central to the company's operations, developing flagship products like Intel's CPUs. While local consolidation and job cuts may occur as part of the global restructuring, full closure or relocation seems unlikely.

A final question is what role the Kiryat Gat plant will play following the foundry division's spin-off, as it mainly produces Intel chips. The company is expected to address this soon as more details about the plan emerge.

Amid these sweeping changes, Intel also announced two pieces of positive news. First, it signed a strategic partnership with Amazon’s cloud division, AWS, to co-develop AI chips, which Intel will produce through its foundry. This multi-year, multi-billion-dollar agreement highlights Intel’s critical role in AWS's AI and server chip strategy. Second, the Biden administration has awarded Intel a $3 billion contract under the CHIPS Act to build dedicated chip manufacturing capabilities for the U.S. defense industry.

These deals represent more than immediate revenue—they are a vote of confidence in Intel’s future from key global players and industries with strict standards. They send a clear message to the market: while Intel may be struggling, it is making bold moves to stay competitive and deliver advanced products.

One of the most noteworthy examples of a successful Hail Mary pass came exactly 30 years ago, in September 1994, during a game between the University of Michigan and the University of Colorado. Quarterback Kordell Stewart launched a 64-yard pass into the hands of receiver Michael Westbrook, clinching a game-winning touchdown in what became known as the "Miracle at Michigan."

Now, 30 years later, Intel is hoping its Hail Mary will lead to a similar outcome, though with far more at stake than a football game. The ball is in the air. Now we wait to see if there’s someone on the other side to catch it.