Robots in movies: Future reality or metaphor?

In reality, robots are functional machines devoid of morals and emotion, but thanks to the cinema they gain human qualities, hold beliefs and opinions, and become the clear representatives of a bad or better future. This is how the screen turned the robot into a very portable computer with a human heart beating in its chest

Tell me who your robots are and I'll tell you who you are. When you make a futuristic film with robots in the center - are they human-like or monster-like? Do they have a face with eyes and a mouth, or are they just an iron plate with a red light bulb? Are they murderous creatures or lifesavers? In short, are you living in a horror movie or a Disney movie?

Like many elements of the worlds of horror films and science fiction—for example, aliens and ghosts—robots are merely a metaphor. Unlike aliens and ghosts, robots are starting to enter more and more into our reality, but still, not the way they are presented and accepted in the movies. In reality, robots look, for example, like a giant arm for digging pits (like the robot that is in front of me now in Rabin Square, and is used to build the subway), there are also underground mining caterpillar robots or robots that carry the lunches of Amazon customers on the streets of Los Angeles. At the last expo in Dubai, for example, there were child-sized robots, with a sweet voice and a smiling face animated by LEDs, who approached passers-by and offered them help in finding the destination they were looking for. They were cute toys, but none of them worked. The robots were lost.

In contrast, in the cinema, robots do not represent the present but are elaborate metaphors for the way the filmmakers imagine the future, and in their image is embodied the answer to the question of whether the future holds for us a utopia or a dystopia.

Human over robot

The word robot was introduced into the world by the Czech writer Karl Capek 104 years ago, when he wrote about human-like machines and gave them the name "robot", because "robota" in the Slavic languages means work, and robots were, for him, forced laborers, slaves. They came to the cinema seven years later, in the film "Metropolis" by Fritz Lang, where a scientist creates a robot in the form of a woman, which is supposed to immortalize his dead lover but creates destruction and chaos. This machine was not yet called a robot, but a “man-machine”. But even here it was clear where the cinema was looking: the robots represent a future of danger. Creatures devoid of humanity and without morals, only software and a destructive automatic response.

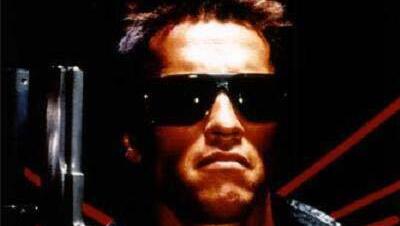

Since then, most of the robots in the movies have been humanized: although there is no objection to making robots in any form (think of the squid robots of the "Matrix", or the dog robots of the US military), the cinema has made the robots into the super-other of man, a human-like creature which is all destruction, with unlimited powers (as long as its battery is charged). They are no longer workers, but prison guards, armed guards, and assassins. We saw murderous robots in "Doctor Who", "The Black Hole", "Saturn 3", and "Westworld" (the original film based on the book by Michael Crichton, who likes to be frightened by futuristic technology); Arnold Schwarzenegger played the famous and iconic robot in "The Terminator", from 40 years ago. In James Cameron's film, the computers go into a state of independent consciousness, launch atomic bombs, and destroy most of humanity, except for a few resistance cells, who fight the computers that have turned all machines hostile to humans. One such machine, a terminator robot, is sent into the past to eliminate the leader of the human rebels before he is born, and only a human being can arrive and stop it from succeeding in its mission.

Seven years later—wanting to bring Schwarzenegger back to the lead role, after he no longer wanted to play villains—Cameron realized that a script is like software: the person who writes it determines its character, and he decided that if the murderous robot from the future was programmed to protect and not kill, that's what he would do. The machine is not bad in itself, it is just programmed that way. And so the Terminator has since turned from a villain to a hero, from a terminator to a protector. Another robot, advanced and shape-shifting, became the enemy that would not stop, nor sleep, nor eat, only rushing forward to fulfill its mission.

The Transformers were right

Two years before "Terminator" came out "Blade Runner" presented the robots as replicants - human duplicates. To such an extent that they are duplicates, that it is almost impossible to distinguish them from humans, and only a rather complicated test - a kind of futuristic Turing test - should clarify who is human and who is artificial. The replicants were created as a workforce, but also in them the free will arises, the one who wants to be like humans, and rule the world, or at least control their destiny. Then you have to eliminate them.

This is the second stage of the robot stories in the cinema, the moment when the creators began to examine the humanity of the viewers and see if it is possible to feel sorry for a machine, simply because it is built like a person (or a child) and not like a baking oven. Steven Spielberg's "A.I" is about exactly that: is there an obligation to pity and protect a robot that is built like a child? Spielberg's robots represented the other for him, the one who was persecuted and hunted just because he was different, just because the humans were afraid of him. Spielberg imagined the robots as the Jews of the future, who are persecuted, imprisoned, and destroyed.

Will Smith in "I, Robot" created a very free paraphrase of Isaac Asimov's book, in which the robots are the slaves of the future, so there comes a moment when they rebel against humans and demand freedom and rights. Will there be parties in the future that will demand equal rights for robots, and allow humans and robots to legally marry? From Blade Runner to A.I., these films have used a futuristic scenario to ask an age-old philosophical question: What is the essence of humanity? What makes something inanimate human? And what does it mean to be human? Thus the cinema, by presenting robots on the screen, asks the ethical and moral questions that it is not certain that the engineers in high-tech companies are dealing with.

In recent decades, the film industry has realized that its tendency to turn the different and the new into a hostile, violent, and frightening character is a bug of the cinema itself, and not of the technology, and just as the early robots represented absolute and unscrupulous evil, so the new robots can represent good faith and benevolence. And so for every murderous "M3gan", you will find a kind robot, one that you will be happy to adopt as a souvenir toy, certainly if it comes from an animated film. "WALL-E", for example, is a robot that cleans up the filth that humanity has left behind, with big eyes and a romantic inclination. Or Baymax, the healing robot from "Big Hero 6" that looks like a big fluffy bear. Or the "Iron Giant", who, a bit like E.T., gets lost, is persecuted for being different, and finds redemption and mercy thanks to a child.

In the end, the Transformers were right. When it comes to robots - like everything in life - there are bad sides (the Decepticons) and there are good sides (the Transformers) and they fight each other, again and again, from movie to movie, they keep fighting each other. The good against the bad, until the absolute victory. Because the representation on the screen is merely a projection of the creators and the audience onto unrealistic characters that are, after all, metaphors.