Can Israel survive a nuclear strike?

While a direct hit would be catastrophic, nuclear expert Dr. Ori Nissim Levy says survival is possible under the right conditions and explains what Israelis can do to protect themselves in the event of a nearby nuclear explosion.

"If a nuclear bomb falls directly on us, there is nothing we can do. In such a scenario, we will not survive, regardless of any actions we take. However, at a distance of 1 to 1.5 kilometers from the explosion site, survival is possible—and we can and should take protective measures. Israel will not be wiped off the map."

After more than 500 days of war, which has exposed Israeli citizens to a range of threats, Dr. Ori Nissim Levy, a nuclear defense expert, believes the time has come to educate the public on how to protect themselves—not in the event of a direct nuclear strike, but in the case of a nearby detonation.

What can we do?

"Go to a bomb shelter or any underground space to avoid exposure to the blast zone. Even a standard shelter or safe room provides significant protection. If you don’t have access to one, dig a hole—deep enough so that when you stand in it, your head is at least 30 cm below ground level. A tractor can dig such a pit quickly," Levy advises.

How does a simple pit protect against a nuclear explosion?

"One of the most devastating effects of a nuclear detonation is the blast wave, which moves at hundreds of kilometers per hour. It generates intense heat—up to 3,000 degrees Celsius—incinerating everything in its path almost instantly. Cars turn into fireballs, igniting one another within seconds. Fires are the number one cause of destruction following a nuclear explosion."

Will a regular building offer protection?

"To some extent—if you’re not near windows, glass, or porcelain tiles, which can shatter and cause severe injuries. Staying inside a structurally sound building, away from external walls, reduces your risk."

But in Hiroshima and Nagasaki, entire buildings were destroyed over a wide radius.

"The construction materials in those cities were primarily wood and paper. However, in Hiroshima, people inside the stone-built post office—just 200 meters from ground zero—survived because the structure remained intact. That building still stands today."

What should we do before and after the explosion?

Before the detonation, a bright flash of intense light will occur. Levy warns against looking directly at it to avoid blindness. After the explosion, nuclear fallout poses a serious hazard. "If you survive the first 48 hours, your chances of long-term survival increase significantly. The famous mushroom cloud disperses, and within two weeks, radiation levels drop substantially. Unlike a nuclear reactor leak—such as the Chernobyl disaster, where a radiation cloud spread over vast distances—fallout from a bomb decreases more rapidly."

How can we assess the level of nuclear fallout around us?

"Radiation is absorbed by materials like stone, water, and leaves. A simple test is to place a smooth sheet of paper outside; if it remains smooth, it’s relatively safe to leave your shelter. Upon returning indoors, immediately change your shoes, shower, maintain strict hygiene, and avoid consuming any food that was exposed. Only eat from sealed packages or canned goods. Additionally, avoid touching objects outside, as they may be contaminated with radioactive particles. These are crucial survival measures the public must be aware of."

4 View gallery

Bombing of Nagasaki, and surviving buildings near the epicenter of the explosion in Hiroshima, 1945

(AP)

The mystery of the Iranian threat

Levy (57) is a lieutenant colonel (res.) who, over the past year and a half since October 7, has spent approximately 200 days on reserve duty with the National Emergency Authority (NEA). He has commanded hundreds of reservists responsible for managing coordination between government ministries and local authorities. He holds a bachelor's degree in electronic engineering, an MBA, and a doctorate, which he submitted in 2016, in which he analyzed nuclear risk management by governments and developed an international model for nuclear defense—the ONDM (Operational Nuclear Defense Model). For the past eight years, he has headed the World Nuclear Forum, which brings together scientists and experts in the field. He advises various countries and international organizations, lectures extensively, and invests significant effort in raising public awareness of nuclear defense. “The public is thirsty for information. The lack of knowledge is alarming, and it may be influenced by biases,” he says.

We’ll get to those who might have an interest in keeping the public uninformed, but first, it's important to understand how someone becomes an expert in one of the most terrifying threats imaginable. “I've been working on emergency preparedness for years. In the Home Front Command, for example, I was responsible for developing large-scale exercises for extreme scenarios,” he explains. “When choosing my doctoral research topic, I wanted to focus on an area that was underexplored. While many experts study nuclear attacks, there was surprisingly little discussion about nuclear defense.”

Levy is married, a father of three, and lives in Modi’in, where even at home, nuclear preparedness is a topic of conversation. “I talk to my children about emergency readiness, and sometimes we watch relevant films together, such as those about the disasters in Chernobyl and Fukushima. They cooperate with me—to a certain extent.”

What does the home of a nuclear defense expert look like? Is it fully prepared for extreme scenarios?

"No, my family's preparedness is fairly basic," he admits.

What does that mean?

"First and foremost, I don't panic, because that's the most important principle in this field. I don’t have a nuclear shelter, and I haven’t dug a bunker in my yard—I have a safe room. I also don’t hoard large quantities of canned food. I simply ensure that we maintain the standard level of emergency preparedness recommended for every citizen.”

The emergency in question is largely tied to Iran, which poses the main nuclear threat to Israel and continues to advance its capabilities in this area. According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), which tracks global conflicts and weapons proliferation, nine countries currently possess nuclear weapons, with a combined arsenal of approximately 12,000 warheads (as of a June report). Estimates suggest that Israel possesses between 90 and 300 warheads—though Israel has never officially confirmed or denied its nuclear capabilities. Iran, for now, is not on the list.

But that’s hardly reassuring.

"Iran may already have a military nuclear capability," Levy warns. "We have experts in the World Nuclear Forum who believe it does."

What is their assessment based on?

"Four months ago, there was an earthquake in Iran that may have been the result of a nuclear test. There is an international treaty banning such tests, so if one was conducted, it would likely have been underground—producing seismic effects similar to an earthquake. Some scientists who analyzed the seismic data from Iran have not ruled out this possibility.”

There is no official confirmation—neither from Iran nor from any other international source—regarding the events of October 5 in Iran’s Semnan province, about 100 km southwest of Tehran. However, research institutes worldwide detected unusual seismic activity that day, measuring 4.4 on the Richter scale. This magnitude is consistent with a small underground nuclear test, similar to those previously conducted by the United States, Russia, India, and Pakistan.

Breaking the silence

October 5, by the way, came exactly four days after October 1, the night of the second Iranian attack on Israel, during which Iran launched about 200 missiles at Israel within minutes. "I think Iran’s two direct attacks on Israel, in April and October, were tests of their capabilities," says Levy.

If that is indeed the case, and we are approaching the core issue, the question is whether Israel is prepared for it—whether Israel can defend itself against a nuclear attack.

"In this regard, Israel is in a weak position, ranking among the countries least prepared for a nuclear threat. Every time a new prime minister and defense minister take office, the forum of which I am a member sends them an official letter emphasizing the need to establish mechanisms to prepare the Israeli public for nuclear events. They don't even respond. Once, Tzachi Hanegbi (head of the National Security Council) replied, acknowledging the importance of the issue and stating that he would pass it on to the 'relevant authorities.' Since then, we haven't heard anything from anyone."

By "relevant authorities," he does not mean the Atomic Energy Commission. "Under Israeli law, the commission is responsible only for the facilities in Yavne and Dimona. If a nuclear incident were to occur in Netanya, for example—possibly due to damage to the transport of radiological materials used by hospitals or laboratories—there is no clearly designated professional body responsible for handling it."

Levy believes the state's lack of preparedness, and even more so the public’s lack of knowledge, is deliberate—"probably for political reasons," he says.

Why keep the public in the dark?

What does that mean? Why would they want to withhold this information?

"I’ll be careful with my words and say this: The public is not educated on nuclear defense because someone likely prefers the issue to remain perceived as dramatic, overwhelming, and terrifying. Some leaders gain political leverage by instilling fear. Is there a better way to control a population than through intimidation?"

But is the Israeli public even ready for such a discussion? Are people willing to engage in a discourse about life and death in the shadow of a nuclear mushroom cloud?

"If I ask you what to do in the event of a nuclear bomb and you tell me you don't know—that's unacceptable. In my opinion, the public is thirsty for information. This isn't necessarily a conversation about ‘preparing for nuclear war’—it can be framed more broadly as general emergency preparedness, covering war, earthquakes, pandemics, tsunamis, and threats involving nuclear or chemical agents. There are many scenarios the public should be prepared for, and it can be done without creating panic. But any initiative in this area is blocked from above. They don’t want to discuss nuclear weapons here, and those who do want to talk about it find their efforts restricted."

Censorship or neglect?

Are you referring to yourself?

"It’s not that someone explicitly tells me or my colleagues, 'You can't talk about this,' but we approach national leaders every year, urging them to develop plans for increasing public awareness of nuclear defense, and they don’t respond—this has been the case for years. We’re intelligent people; we recognize when there’s a deliberate effort to avoid a topic. After all, the public is given instructions on how to prepare for war, for earthquakes, and during a pandemic. But when it comes to nuclear threats—whether from an attack or an accident—there is complete silence."

Before the escalation on the northern front, the defense establishment and the IDF debated whether to launch a campaign to prepare the public for a potential large-scale Hezbollah attack. They ultimately decided against it, fearing it would cause panic. So now you expect them to brief the public on nuclear bombs?

"Yes, because clear and reliable information actually reduces fear. Fear thrives on uncertainty. We can explain, for example, that 1,000 conventional missiles aimed at the same location are more destructive than a single nuclear bomb—though, of course, I do not downplay the devastation of nuclear weapons. Moreover, after 1,000 precise missile strikes, an area is easier to conquer, whereas nuclear fallout creates long-term contamination issues."

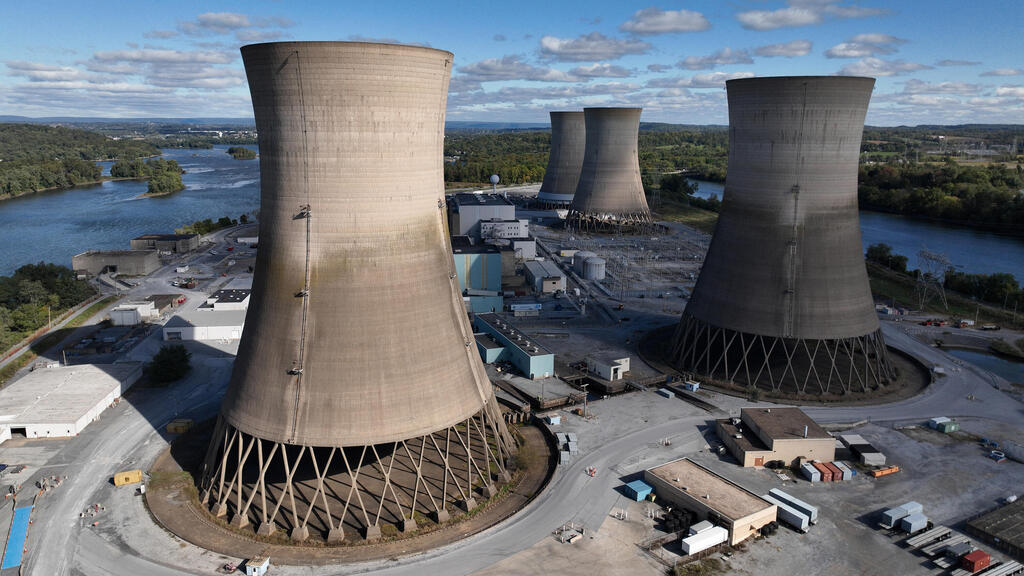

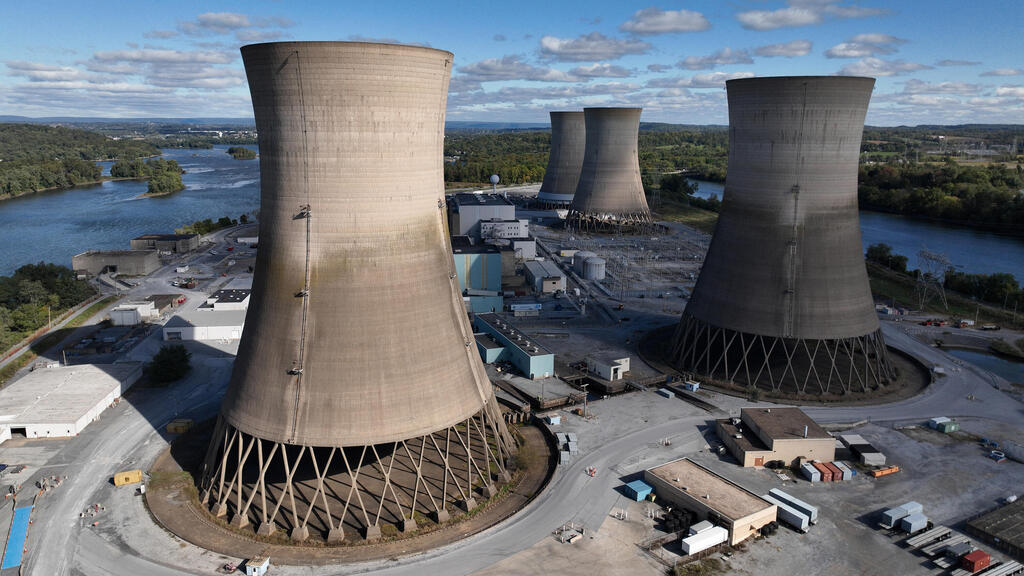

4 View gallery

The Three Mile Island nuclear power plant in Pennsylvania to be used by Microsoft

(Photo: AFP)

Educating the public

How do you propose explaining this to the public?

"We have prepared a guidebook on how to respond to different types of nuclear events, and next week we will distribute it to participants at the annual conference of the Israeli Society for Quality." The conference brings together hundreds of experts, including doctors, engineers, industry leaders, and public sector officials focused on improving safety and quality standards.

But these are professionals. Shouldn’t the wider public be the target? For example, shouldn’t this be taught in schools?

"The World Nuclear Forum, of which I am a member, tried to implement such training in Israeli high schools. We developed a program for physics teachers, who could have incorporated nuclear preparedness training into their curriculum. The Ministry of Education rejected it, saying the program was not created by someone with a bachelor's degree in education. We explained that it was developed with the help of nuclear physics professors—but that didn’t seem to matter. In my view, this is criminal neglect. Why withhold vital information from the public? Why not teach people how to protect themselves? The education system is the perfect framework for such training. During the Cold War, the U.S. had nuclear preparedness drills. Today, similar programs exist in Europe. The need is clear."

This is especially frustrating for Levy, given his familiarity with nuclear defense programs worldwide. In his own country—arguably facing one of the most direct nuclear threats—there is no preparation, certainly not on par with nations that are far less at risk.

What other countries are doing

Levy has studied nuclear preparedness in seven countries, ranking their readiness for a nuclear event.At the top of the list? Switzerland.

"It has hundreds of thousands of well-equipped shelters—enough to house the entire population. Every newborn has a designated bed in a shelter, along with emergency food supplies and clean water. Some of this infrastructure is outdated, but it still exists and is maintained."

Which other countries rank highly?

"Finland is second, having significantly improved its readiness since Russia's invasion of Ukraine. France is third, followed by Germany, Canada, and the United States. Israel is dead last among the countries I examined."

What about preemptive action?

All of this pertains to nuclear defense and preparedness. But what about preventing an attack in the first place—denying Iran the ability to strike Israel with nuclear weapons?

"I don’t understand why Iran’s nuclear facilities haven’t been bombed yet. I really don’t. There were clear opportunities—after Iran’s two direct attacks on Israel in April and October—and it seems the window has closed. In April, perhaps we hesitated, but after the heavy barrage in October, another opportunity presented itself. In both cases, we had international legitimacy, since Iran had attacked us, and we had the operational capabilities. We’ve already struck other targets in Iran, and we’ve attacked in Yemen. We've overcome the challenges of distance, aerial refueling, and more.

“And now, Donald Trump is in the White House again, and he wants a new agreement with Iran. We've had bad experiences with these agreements before, but I don’t see anyone here acting against U.S. policy. I just hope we don’t look back in the future and regret missing a golden opportunity."

What are the chances of a worst-case scenario?

To understand the nature of the threat to Israel, it is necessary to first examine the types of nuclear bombs and their capabilities. Nuclear warheads can be launched on intercontinental ballistic missiles and, according to Russia, on hypersonic missiles, which are very difficult to intercept due to their extreme speed. Warheads can also be dropped from airplanes or launched from submarines. Additionally, there are tactical nuclear weapons, which are designed to hit a relatively small area with less destructive power but can still devastate a vital base or a large concentration of military forces.

The bomb dropped on Hiroshima had a yield of about 15 kilotons of TNT and was based on enriched uranium—similar to what Iran is believed to be attempting to produce today. The bomb dropped on Nagasaki had a yield of 21 kilotons and was based on plutonium—like what Israel is believed to possess, according to foreign reports. Syria also attempted to develop a plutonium-based bomb with North Korea's assistance until its reactor was destroyed in 2007. However, nearly 80 years have passed since the bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. Today, nuclear weapons are measured not in kilotons but in megatons—hydrogen bombs with exponentially greater destructive power.

What does this mean?

Levy explains that if a 15-kiloton nuclear bomb were to strike Tel Aviv at night, when people are at home, the death toll would be around 5,000. "I don’t take even a single death lightly, of course, but this would not mean the destruction of the State of Israel. It would not result in millions of deaths, nor even half a million."

However, we have now entered the era of megaton weapons.

"Yes, and a 1-megaton bomb is already a hydrogen bomb in which the nuclear explosion serves only as the trigger."

What if such a bomb were to strike Tel Aviv at night?

"In that case, we would be dealing with a dramatic and catastrophic event. God forbid."

Would Tel Aviv be obliterated? Would Gush Dan become a wasteland?

"No, even then, Tel Aviv would not be completely wiped out. But the damage would be immense."

Should we fear such a scenario?

"I don't see the superpowers—Russia or the United States—using such weapons against Israel."

And Iran? Could it build such a bomb?

"It’s not that simple. Developing a hydrogen bomb is significantly more complex than producing an atomic bomb. It requires different production infrastructure, specialized knowledge, and extensive testing. Someone who manages to produce a 15- or 20-kiloton bomb cannot simply tweak it to create a 15-megaton bomb. However, from Iran’s perspective, the exact power of its nuclear weapons is secondary. The real issue is its ability to become a nuclear state, which is more about possession than capability."

Google and Meta’s nuclear race

While Iran is a major concern for Israel, it is not the only nuclear threat worrying the world. The global nuclear arsenal is dominated by the United States and Russia, which together possess 90% of the world’s nuclear weapons. China, with an estimated 500 warheads, is the third-largest nuclear power, followed by France, the United Kingdom, India, and Pakistan. Israel is ranked eighth, and the list is rounded out by North Korea, which possesses "only" 50 nuclear warheads.

For years, nuclear fears centered on tensions between India and Pakistan, and occasionally between North Korea and the United States. However, Russian President Vladimir Putin has brought the nuclear threat back into focus amid the war in Ukraine. In response, European nations have invested billions in air defense systems—some purchased from Israeli companies—increased their defense budgets, and strengthened their armed forces. In the summer, SIPRI Institute director Dan Smith warned, "We are in one of the most dangerous periods in human history."

The "Doomsday Clock," established in 1947, measures how close humanity is to global catastrophe, particularly nuclear disaster. Originally set by atomic scientists at the University of Chicago, the clock is periodically adjusted to reflect global threats. In January 2024, it was set just 89 seconds to midnight—the closest to disaster since its creation. For comparison, the furthest it has been from midnight was 17 minutes in 1991, following the collapse of the Soviet Union and the signing of the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons.

Beyond geopolitical tensions, fears of nuclear disasters persist. From Chernobyl to Fukushima, nuclear accidents continue to shape public perception. Meanwhile, the surge in artificial intelligence development has significantly increased global energy demands. As a result, tech giants like Microsoft, Oracle, Meta, and Google are investing in nuclear reactors or securing long-term agreements with nuclear energy providers to meet their growing electricity needs.

"By all indications, this year will be a turning point for nuclear energy, driven by the immense interest of technology companies," says Levy. "Currently, nearly 10% of global energy comes from nuclear sources, and the sector is expanding. In Germany, for example, there is widespread criticism of former Chancellor Angela Merkel’s decision to shut down nuclear power plants after the Fukushima disaster."

What about nuclear energy in Israel?

"My colleagues at the World Nuclear Forum and I believe that Israel is making a mistake by not engaging in nuclear energy development. A designated site in the Shivta region in southern Israel has already been allocated for a nuclear power plant. Once the government decides to act, it will be built there. Within the Ministry of Energy, discussions and staff work on the matter have taken place in recent years. However, a meaningful public debate is needed to move forward. In many countries, public awareness campaigns have successfully changed perceptions about nuclear energy."

Given Israel’s small size, is a nuclear power plant really necessary?

"I believe so. A small reactor could be an option, and in any case, advancing this field would benefit the country. Universities would expand their nuclear engineering programs, pushing Israel forward technologically."

Levy argues that this progress is essential because "the world is undergoing an extraordinary and rapid transformation." The demand for nuclear energy and the growing arms race are two sides of the same coin, both unfolding amid ongoing fears of catastrophe. Just last weekend, Ukraine released footage of an explosive drone striking the protective dome over the remains of the Chernobyl nuclear power plant. This dome was erected to prevent further radioactive contamination, but now, there is a hole in it.

Will the "World Nuclear Year," as Levy calls it, mark the beginning of a new era of disasters? He remains calm, neither stockpiling supplies for doomsday nor succumbing to panic. "I can’t say that nuclear weapons will be humanity’s greatest problem in the coming years," he says. "We are witnessing massive global shifts—wars, political upheavals, trade conflicts—and nuclear threats are just one aspect of this broader transformation. Only time will tell their true impact."