The Semiconductor Showdown: US-China trade war escalates with export restrictions

China's move to limit metal exports for chip industry sends shockwaves through global tech supply chain, prompting concerns over chip shortages and economic impacts

The offices of Samsung's management in Seoul still remember that gloomy day on July 30, 2020, when the sales data of smartphone manufacturers for that quarter were published, revealing that the Chinese technology company Huawei surpassed Samsung for the first time, becoming the global leader in the field. Until then, Huawei had been trailing behind Samsung and Apple, but during that period, it enjoyed a sales rate of over 200 million smartphones per year.

Shortly after that, the situation reversed again. This time, not due to a new strategic plan or a hot device, but for an entirely different reason: the U.S. government prohibited the sale of chips, a vital component in smartphones, to the Chinese Huawei, if those chips were made in the United States or involved the use of American technology. The U.S. government alleged that the Chinese government was implanting surveillance measures in the company's devices. The impact of the ban was dramatic: Huawei's sales dropped to less than 30 million smartphones in 2022, an 85% decrease within two years.

4 View gallery

U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and Chinese Prime Minister LI Qiang

(Credit: EPA/Mark Schiefelbein / POOL)

Since then, chips have become the heart of the trade war between the United States and China, which began during the tenure of former President Donald Trump. His successor, Joe Biden, intensified the steps taken by his predecessor, and in October of last year, he imposed the most severe sanctions ever on China, prohibiting American citizens and companies from working with Chinese companies engaged in advanced chip manufacturing without a special license.

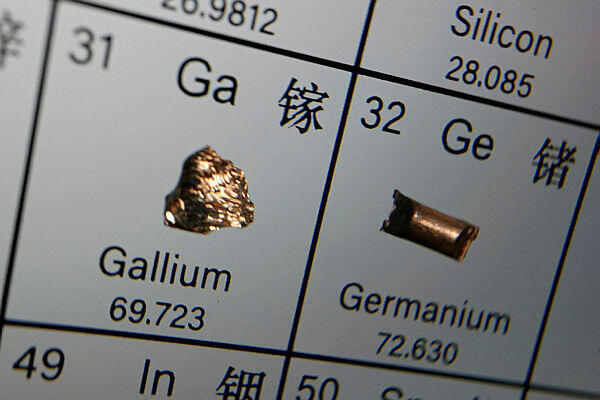

Two weeks ago, the Chinese response arrived, with China announcing that it would limit the export of metals such as germanium and gallium, which are used in the chip industry. These are the very chips that make up smartphones and are found in almost every electronic product today, from washing machines, refrigerators, and cars, to advanced missiles.

In many ways, the Chinese announcement of restricting exports of metal products was expected. China, responsible for producing about 68% of germanium products and approximately 80% of gallium products worldwide, probably anticipates further American sanctions that are expected to take effect soon. Thus, China seeks to create significant leverage in trade negotiations with the United States. It is reasonable to assume that the timing of the announcement on July 3rd was carefully chosen, just a few days before the visit of U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen to Beijing.

An article published last week in the newspaper China Daily, owned by the state, hinted that Beijing's new policy is a response to similar moves made by Washington and its allies. The article stated that those who criticize China's decision could ask the U.S. government why it holds the world's largest germanium mines but rarely utilizes them. Or they could ask the Netherlands why it includes certain products related to semiconductors on its export control list.

Simultaneously, the Chinese announcement on export restrictions was widely discussed on Chinese social media. The majority of internet users expressed support for the move, seeing it as necessary and symbolizing China's refusal to yield to pressure and sanctions aimed at hindering its progress. The prevailing opinion among users was that the United States was acting hypocritically and the Chinese announcement was a legitimate response, albeit somewhat delayed.

A gradual shift

The United States and China are each other's largest trading partners, and their economic interdependence has deepened over the years. For many leading American companies such as Apple, Tesla, Nike, McDonald's, General Motors, and Ford, China is one of the most lucrative markets. In 2021, for example, Apple sourced more components in China than in any other country, including the United States.

China's economy benefited from its trade relations with the United States, leading to the creation of millions of jobs in China. Over the years, the United States was one of the most significant exporters to China, alongside Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The common denominator among these four countries is that they all export chips to China - a lot of chips.

The change in relations between the countries has been gradual, but is often attributed to the policy led by former U.S. President Barack Obama, which included greater involvement and investment in Asia-Pacific countries to weaken China's influence in the region ("pivot to Asia"). In response, China launched "Made in China 2025" in 2015, a strategic program aimed at raising China's position in the global value chain, no longer to be the world’s cheap factory, but a powerhouse of advanced technology products such as communication networks, chips, robotics, and electric cars.

China claimed that the program was designed to boost domestic production, help the economy break free from the "middle-income trap," and reduce its dependence on foreign countries regarding strategic core products. However, in the United States, "Made in China 2025" was perceived as a direct threat to American technological dominance. From there, relations took a downturn.

The escalating struggle

Tensions between the countries intensified during Trump's presidency, as he identified China as the source of problems for the United States even during his election campaign. In 2018, Trump launched a trade war against China by raising tariffs on Chinese goods worth billions of dollars, including on semiconductors used for chip manufacturing. He justified this move by claiming that trade between the countries was imbalanced and he sought to protect American intellectual property. The struggle between the two sides continued, but Trump's affinity for "closing deals" enabled the signing of trade agreements in which China committed to purchasing American goods in exchange for reducing tariffs and sanctions.

However, another significant move made by the Trump administration was to impose sanctions on Chinese tech companies, mainly in the communication and semiconductor sectors, with Huawei being the primary target. Huawei was one of the crown jewels of the "Made in China 2025" program, positioning itself as the global leader in the fourth generation of cellular communication technology (4G networks), alongside Ericsson and Nokia. In the fifth generation (5G) of cellular communication networks, Huawei had already emerged as the global leader due to its innovation and technological superiority.

The United States, along with some prominent Western allies, banned the use of Huawei's 5G networks and called on other countries not to use Huawei's communication equipment, alleging that the Chinese government used it for spying. The accusation was never substantiated, but American pressure, coupled with the fact that the United States itself used similar surveillance methods, as revealed in WikiLeaks documents, led many countries to avoid using the company's products.

At the same time as its rise in communication networks, Huawei became one of the leading manufacturers of cellular phones in the world. After being crowned the top seller of smartphones in the second quarter of 2020, it faced American sanctions. Once again, the United States claimed that these sanctions were imposed to protect its national interests and security.

Due to the sanctions, the company's sales were significantly affected. In 2021, they sold only about 35 million smartphones, and in 2022, less than 30 million. The company's revenues, which grew at a rate of 10-30% annually in the previous decade, reached a peak of about $134 billion in 2020, but in 2022, they declined by a third to just $88 billion.

When President Biden entered the White House, some in Washington feared that he would adopt a more lenient policy towards China and refrain from imposing further sanctions. However, the opposite happened. Under the Biden administration, the United States intensified its actions against China and focused on the rising power's vulnerable point: the semiconductor industry. The U.S. based this move on the dual-use of advanced chips, not only for civilian industries but also for military and intelligence systems.

In October of last year, the American government announced a sweeping move that affected all advanced semiconductor industries in China. It prohibited American citizens and companies from working with Chinese companies engaged in the production of advanced chips without a special export license. Experts who addressed the issue were concerned that obtaining the license for producing complex chips would become more challenging. The goal of this move was likely to prevent China from advancing in its chip manufacturing capabilities and thus hinder its development of various strategic technologies, such as artificial intelligence or supercomputers.

Similar to the restrictions on Huawei, the United States also urged leading companies in innovative chip technologies to move away from China, primarily in Japan and the Netherlands. Concurrently, the U.S. added 31 Chinese companies, including YMTC, a memory chip manufacturer that supplies components for iPhones, to its "unverified" list, which is typically one step before placing them on the blacklist, prohibiting American companies from working with them.

Besides the Chinese chip industry, the combination of moves also hurt the revenues of some of the leading American companies such as Nvidia and AMD, both because it made production processes and the use of the best components more difficult, and because they had to stop selling their newest and most expensive products to the world's largest market. In 2021, Nvidia's revenues from China reached about seven billion dollars, and it is estimated that despite the jump in the company's profit forecasts in light of progress in the field of artificial intelligence (AI), cancellations of orders from China prevented the increase from being even greater.

At least a five-year gap

The case of Huawei exposed to the world China's soft underbelly - the advanced semiconductor industry. For decades, China has built a monopolistic position in most stages of the production chain of several critical materials, particularly for various electronics products, including chips. It starts with access to raw materials in countries in the global south and becomes even more significant in processing these materials and turning them into products used by chip manufacturers worldwide. Processing these materials is not an exceptionally complex task, but it is a highly polluting industry that Western countries seemed to be willing to let China take over.

However, for some stages of production, China requires capabilities that it has not yet developed. Many companies can design high-level chips, including some Chinese companies, like Huawei's subsidiary, HiSilicon, which designed the advanced chips used by the parent company. In contrast, chip manufacturing, especially advanced chips in technology of seven nanometers and below, is a complex matter that requires enormous financial investment, high expertise, and specialized equipment. Even a chip manufacturing giant like Intel struggles with it, and there are only two companies capable of producing chips in technology more advanced than seven nanometers - Samsung from Korea and TSMC from Taiwan. The latter, the world-leading manufacturer, was also Huawei's chip supplier.

The sanctions announced by the United States in October prevented TSMC from continuing to produce advanced chips for Huawei, even though the latter was one of its biggest customers, and despite the fact that TSMC is not an American company. This is also because American technological capabilities were involved in the chip manufacturing process, and the company did not want to risk getting entangled with the United States and the major companies it manufactures for, such as Qualcomm, Nvidia, and Apple.

Following the sanctions, Huawei was forced to turn to local chip manufacturers in China, but even the largest and most advanced among them, SMIC, is far from the production capabilities of Samsung and TSMC, and estimates suggest it lags behind by at least two generations of production capabilities. To bridge the gap, China took several actions simultaneously. Firstly, China invests massive amounts, estimated in hundreds of billions of dollars, in encouraging research and development in the field. However, such research takes years.

Secondly, several reports indicate that China is responsible for cyber attacks on Taiwanese companies to obtain sensitive information about chip manufacturing. Some reports include evidence such as instructions in Chinese, working hours synchronized with those in China, and other identifying signs. In addition, Chinese companies invest significant resources in recruiting foreign experts, and according to some reports, thousands of Taiwanese employees were offered double their salaries to bring their knowledge and expertise to China.

However, even with these efforts, it will take China at least five years to bridge the gap in chip manufacturing, while it is reasonable to assume that during that time, Samsung and TSMC will also advance. The Chinese government understood this and thus has been actively exerting significant pressure to reduce the impact of the American sanctions or at least prevent them from expanding. Initially, the Chinese government took actions against specific American companies in the chip industry. Among other things, China piled regulatory difficulties, ostensibly due to business restrictions, on Intel's acquisition of the Israeli chip manufacturer, Habana (the Chinese regulator could be involved in approving the deal as Intel's revenues in China reach billions each year). China also imposed restrictions on Chinese companies from using products from the American memory chip company, Micron. However, these actions did not accumulate into a significant response, until about two weeks ago, when China announced export restrictions on products used in the chip industry.

Far-reaching implications

The Chinese announcement is expected to have broad economic and technological implications that will affect the global economy as a whole, including China itself, which heavily relies on exports. Among other things, chip manufacturers outside of China are expected to be affected, and in the short term, there is expected to be a significant shortage of certain types of chips. Additionally, since chips based on Chinese raw materials are used in almost every type of electronic device, the restrictions are expected to impact other products as well, such as LED screens and solar panels. "I think the move will not achieve its goal because it will only strengthen the determination of many countries in the world to reduce risks," said Jake Sullivan, the United States' national security advisor, this week.

The founder of TSMC, Taiwanese-American billionaire Morris Chang, has expressed concerns in the past about the competition between China and the United States. Now, he warns that the effectiveness and efficiency of the chip supply chain will be severely affected. In a speech he gave earlier this month in Taiwan, Chang proposed a new definition of globalization, according to which "companies are allowed to expand abroad and bring in products and services of foreign companies only on condition that these activities do not harm national security or the technological and economic leadership of that country."

Simultaneously, Chang criticizes the manufacturing industries in the United States, arguing that their efficiency is lower compared to other countries, but the cost of their products is higher. He might imply that if the same chip, for example, used by Apple, is manufactured in TSMC's factory in Arizona, it would cost 50% more than if it were produced in the company's factory in Taiwan. The question remains whether, following the Chinese announcement of export restrictions on metal products, chip manufacturers will be affected in their profit margins or if the price increase will be passed on to Apple - and whether the latter will impact the broader profit margins of iPhone sales or pass the cost on to consumers.