How Intel ruined an Israeli startup it bought for $2B—and lost the AI race

Habana Labs was supposed to challenge Nvidia. Instead, Intel drove it into the ground.

In December 2020, Amazon announced with great fanfare that it would use Gaudi chips from the small Israeli startup Habana Labs to train its large language models (LLMs) in the cloud. Although generative AI was not yet a household term at the time, it was a major development in the ecosystem. Intel, which had acquired Habana for $2 billion the year before, boasted about the event, calling it “the first crack at Nvidia’s dominance in GPUs.” At the time, Intel and Amazon were the dominant players in the market, while Nvidia was primarily known to gamers who admired the graphics capabilities of its processors. However, Intel’s concerns about its young and ambitious competitor were already evident. Few could have imagined that just a few years later, Nvidia would be trading at a valuation of $3.5 trillion as the world’s largest company, while Intel would be worth only $80 billion.

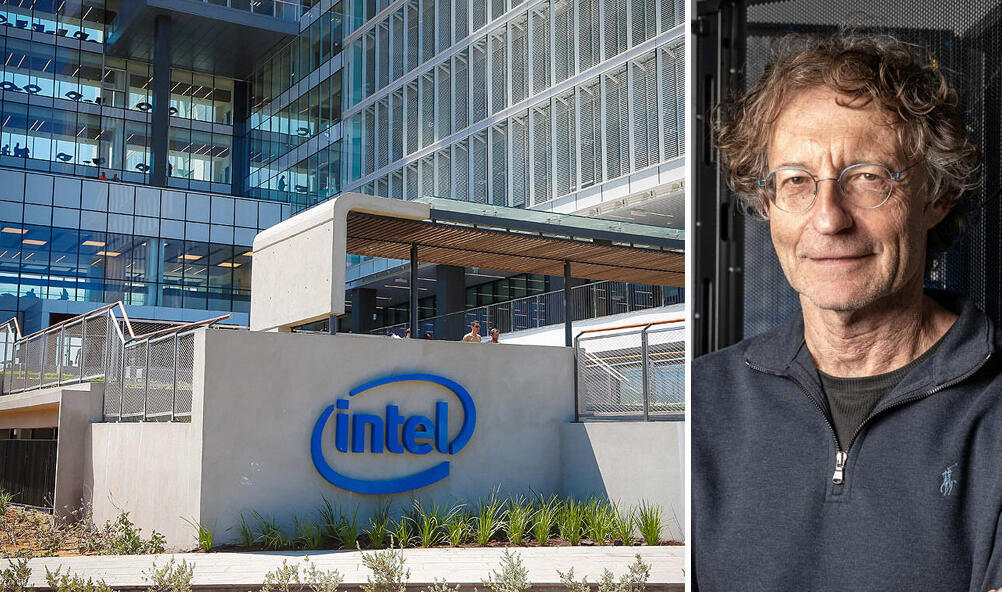

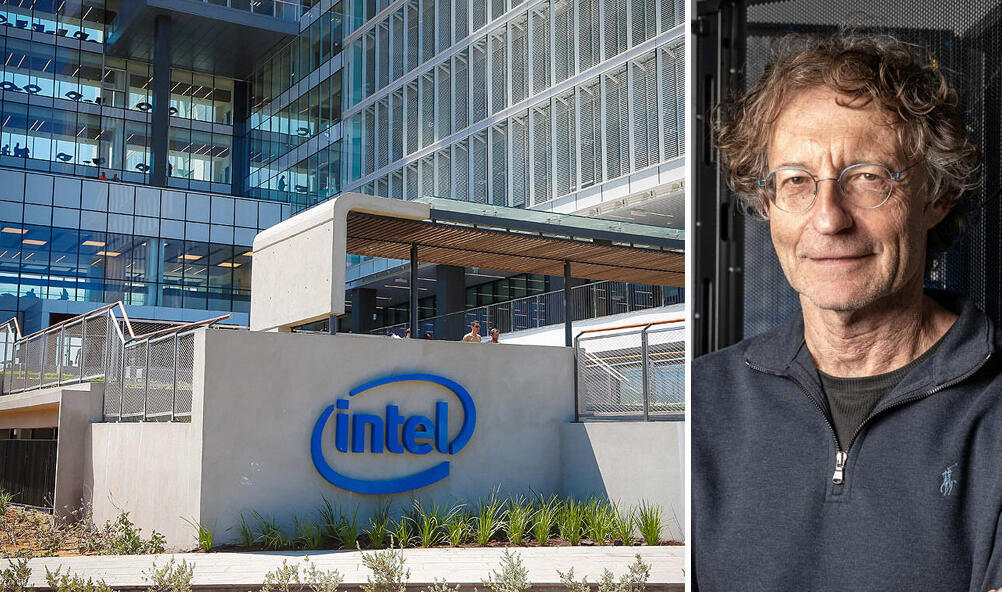

Last week, along with reporting disappointing financial results, Intel announced that its next-generation Habana processor, Falcon Shores, had received negative feedback from customers and would therefore not be marketed commercially. This follows an earlier announcement, about six months ago, that Gaudi had failed to meet expectations of reaching $500 million in revenue by 2024. As a result, Intel decided not to develop another generation of Gaudi beyond the existing Gaudi 3. This effectively marks the failure of Habana Labs as another entry in Intel’s long history of unsuccessful acquisitions. While this outcome may not be surprising for Intel, it is an unusual event in the track record of Avigdor Willenz, the Israeli entrepreneur behind Habana.

1 View gallery

Habana Labs founder Avigdor Willenz and Intel offices.

(Photos: Eyal Toueg and Nir Keidar)

Willenz, considered a genius in the semiconductor world, has a long history of successful exits. His achievements include the sale of Galileo to Marvell for $2.7 billion in 2000, an acquisition that significantly boosted Marvell’s market position. He later sold Annapurna Labs to Amazon for a relatively modest $350 million—small compared to its current crucial role in Amazon’s cloud operations. More recently, he was one of the founders and early investors in the U.S. company Astera Labs, which went public last year at a valuation of $5.5 billion and is now worth $16 billion. Given his record, Habana Labs' failure is a rare misstep and raises the question: What went wrong? The simple answer is likely Intel itself and its well-documented struggles with acquisitions.

Even before the negative announcements about Gaudi and Falcon Shores, Habana Labs had already disintegrated. By 2024, nearly all of its founders, managers, and engineers had left Intel, most of them immediately after their four-year retention period ended. Many did not even wait for Intel’s voluntary retirement plan. Today, almost none of Habana’s original hardware engineers remain at Intel. Recognizing its difficulties in integrating acquisitions, Intel had previously experimented with keeping acquired companies as separate units. It applied this approach to Mobileye until deciding that the structure was ineffective and spinning it back out as a public company. Habana was also kept as a separate unit until last year, when it was dismantled and absorbed into Intel’s existing operations.

The beginning, as usual, was optimistic. Unlike some of its past failures—such as missing the mobile revolution—Intel correctly identified AI as the future. Five years ago, the company projected it would generate $25 billion in AI processor revenue by 2024, a target that remains far from reality. As part of its AI push, Intel acquired the startup Nervana for $400 million. Nervana specialized in processors for training language models, but Intel soon realized it had bet on the wrong technology. In 2017, seeing Nvidia’s rapid advancements in GPUs, Intel recruited Raja Koduri, a former AMD executive, to lead its AI efforts. However, customer feedback remained disappointing—Intel’s processors were underpowered and failed to meet market demands.

To signal its commitment to AI, Intel sought a dramatic move. It attempted to acquire Mellanox but refused to pay the $7 billion that Nvidia ultimately offered in a deal that stunned the industry. Nvidia CEO Jensen Huang had a clear vision for Mellanox’s strategic importance, while Intel hesitated. After losing out, Intel turned to the second name customers had recommended for competitive AI processors: Habana Labs. Founded in 2016 by David Dahan and Ran Halutz—both veterans of PrimeSense, the Israeli company behind Apple's facial recognition technology—Habana already had a functional AI training processor, Gaudi. Unlike Nvidia’s GPUs, Gaudi was based on a different architecture, and Amazon later claimed it was 40% more efficient than Nvidia’s offering. At the time, Amazon was rumored to be interested in acquiring Habana, but Intel, eager to recover from the Mellanox debacle, was willing to pay more. Intel completed the acquisition in 2020, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, and simultaneously shut down Nervana.

Nvidia finalized its Mellanox acquisition around the same time, but the outcomes for the two Israeli companies diverged sharply. Nvidia successfully integrated Mellanox, which now generates over $13 billion in annual revenue and employs thousands in Israel. Meanwhile, Habana Labs floundered under Intel’s leadership.

Sources who spoke to Calcalist about Habana’s downfall unanimously agree that Intel mismanaged the acquisition by pursuing multiple competing AI strategies without fully committing to any. Some believe Intel acquired Habana simply to cover up Nervana’s failure and signal to investors that it was investing in AI—without necessarily intending to challenge Nvidia through Habana. This was evident in Intel’s organizational structure: Habana was not placed under Koduri’s GPU division (AXG) but instead under the data platform group (DPG). Koduri, a high-profile hire at Intel, wielded significant influence and reportedly received the bulk of development and marketing budgets.

"From the moment the Habana acquisition was completed, people inside Intel couldn’t understand why the company was running both Habana and the GPU division, which were developing competing architectures," said a former Intel executive. Former Habana employees also described Intel’s bureaucratic inefficiencies as a major obstacle. "At Habana, we could make a decision in a five-minute hallway conversation. At Intel, that same decision required three meetings with dozens of participants, and nothing moved forward," one former Habana employee recalled.

Until 2022, Intel pursued both strategies simultaneously, selling Gaudi processors while also developing its competing GPU, Ponte Vecchio. However, with the rise of ChatGPT and other generative AI models, Nvidia’s dominance became undeniable, and Intel once again received negative customer feedback. Ponte Vecchio was discontinued in 2024, just two years after its launch, and later that year, Intel announced it would not develop new Gaudi generations. In 2022, following Koduri’s departure, Intel attempted to consolidate its efforts by merging Habana and its GPU division to develop a new AI processor, Falcon Shores—a hybrid chip combining a GPU (like Nvidia’s) with a CPU (Intel’s specialty). At Habana, the move was met with skepticism and wry humor: "Suddenly, they remembered us," some employees joked.

Now, it turns out that Falcon Shores has failed to meet expectations and will be used only for Intel’s internal testing. The company is shifting focus to a new chip, Jaguar Shores, attempting to leapfrog several generations to catch up with Nvidia. However, industry experts believe that closing the gap is nearly impossible. Nvidia has spent the last two decades refining its AI processors, while Intel has only recently recognized the opportunity—arriving late, like a sluggish hippopotamus at a sprinting contest.

Meanwhile, the former Habana team, along with Willenz, has already moved on to its next AI venture from new offices in Tel Aviv. They cannot complain too much—Intel paid in cash, and estimates suggest that Willenz, the founders, and the startup’s 100 employees collectively received around $1 billion. But despite the financial windfall, Habana’s failure is a rare blemish on Willenz’s record and, more importantly, a missed opportunity for Israel. With better execution, Habana could have become the foundation of Intel’s AI strategy instead of another casualty of its troubled acquisition history.

Intel said in response: "Our AI opportunity is centered on solving our customers' most pressing challenges, particularly reducing compute costs and increasing efficiency. A one-size-fits-all approach will not suffice. Instead, we see clear opportunities to leverage our core and existing assets in new ways with the goal of delivering the most compelling total cost of ownership across this continuum.

"Following customer feedback and market dynamics, we are planning to leverage Falcon Shores as an internal test chip and instead focus resources to bringing Jaguar Shores to market. As the foundation of Jaguar Shores, Falcon Shores remains critical to our significant work and its learnings will feed directly into Jaguar Shores."