Is Intel’s time up? TSMC and Broadcom move in as the chipmaker falters

With AI advancements falling short, Intel's future may lie in a breakup, with two major players eyeing parts of the company.

On July 18, 1968, three individuals did something that would change the world. Gordon Moore (the inventor of "Moore's Law"), Robert Noyce (the inventor of the integrated circuit), and Arthur Rock (one of the early venture capitalists) founded a new chip company. They called it "Intel," a portmanteau of the words "Integrated" and "Electronics." Nearly six decades have passed since then, and Intel has become one of the most important companies in the technology world, shaping and advancing not only the chip market but also, to a large extent, the personal computing market. In a brilliant campaign from the 1990s, "Intel Inside," the company got consumers to take an interest in the internal components of the computers they purchased, making decisions based on the presence of a processor—a component many had previously overlooked.

However, it now seems that this once-great company is in a situation reminiscent of vultures circling a dying animal. Potential buyers are beginning to surround Intel, each hoping to carve out a different part of the company. According to reports from Bloomberg, The New York Times, and The Wall Street Journal, two chip giants are considering acquiring parts of Intel's operations: Taiwanese chipmaker TSMC, which is seeking to acquire the company’s manufacturing operations, and American chip developer Broadcom, which is interested in acquiring its chip design and marketing operations.

Both moves are still in the initial, largely unofficial stages. It is uncertain which, if either, will be finalized, and Intel’s intentions are not entirely clear (although interim chairman Frank Yeary is reportedly involved in talks with TSMC). There is a possible scenario in which no deal is made, or Intel sells only part of its operations and keeps the other half, making it more similar to modern chip companies like TSMC or Nvidia, which focus solely on either manufacturing or development. Alternatively, both deals might go through, marking the end of Intel as a company that once created revolutions but has since struggled to keep up with them.

Of the two deals, TSMC's appears to be at a more advanced stage. According to reports, Yeary has been in talks with executives at the Taiwanese company for several months regarding a deal to acquire Intel’s manufacturing operations. One possibility is that TSMC could acquire Intel's manufacturing operations in the U.S., with the option to include Intel's factories in other countries, including Israel. The move would likely involve collaboration with other players, such as technology giants like Nvidia and Apple, and investment firms.

Such a deal would require approval from the U.S. government. Sources indicate that Howard Lutnick, Trump’s designated Commerce Secretary, is involved in the talks and sees this as one of the key challenges in his new role. It is not certain that the administration will support the deal.

Broadcom’s interest is still in the very early stages. According to The Wall Street Journal, Broadcom is examining Intel’s chip design and marketing businesses, and has held informal discussions with its advisers about submitting a purchase offer. However, Broadcom is not expected to submit a bid without first finding a partner to acquire Intel’s chip manufacturing operations. At this stage, no formal request has been made to Intel on the matter. Broadcom and TSMC do not collaborate.

Most of the discussions so far are preliminary and largely informal. However, the involvement of senior executives from both companies and the Trump administration suggests this is more than a mere exploration, indicating that one or both deals may come to fruition. An examination of the interests of the various players reveals that some kind of deal is likely the preferred solution for many.

Missed the mobile revolution

The last two decades have been difficult for Intel. It completely missed the mobile revolution, allowing Qualcomm to dominate the field (and also Apple, which designs all the processors for its devices). Intel still technically has the chance to join the AI revolution and challenge Nvidia. However, its efforts to develop an AI processor capable of competing with Nvidia’s popular chips have faced significant challenges. Just this month, the company announced that the AI processor it developed with technology from Israeli startup Habana Labs would not reach the market, meaning Intel’s response to Nvidia has been delayed by several quarters.

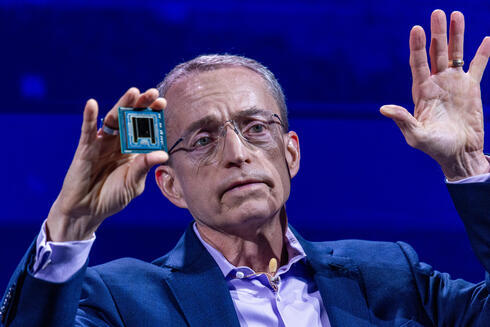

Former CEO Pat Gelsinger hoped to reinvigorate Intel with a strategic plan to establish a foundry division—manufacturing chips for other companies based on their designs—which could potentially bite into TSMC's profitable market share and attract customers such as Nvidia and Apple. While this move has potential, it also comes with fundamental problems (for example, would Nvidia really want to manufacture for its competitor?). Establishing a significant manufacturing division is an expensive and time-consuming process that requires patience from shareholders. Disappointing quarterly results and a surge in losses significantly shortened shareholders' patience, and Intel’s struggle to match the advanced manufacturing capabilities of companies like TSMC and Samsung has eroded confidence in its ability to execute this move. In the meantime, Intel has been forced to make significant cuts to its workforce and operations, and Gelsinger abruptly retired at the end of 2024, seemingly due to a lack of confidence from the board in his leadership.

Intel today is battered and bent, and it seems to have realized that it cannot maintain both manufacturing and design under one roof. While this model worked in the company’s early decades and was central to its success, the structure of the market today suggests that it is better for a chip company to focus on one strength. Nvidia is successful because it dedicates all its resources to designing and developing the best chips. TSMC thrives because it focuses solely on bringing other companies' designs to life and creating the processes needed to develop increasingly advanced chips. If one of the deals goes through, Intel will be free to focus its resources on one of these activities, potentially positioning itself as a leader again.

If both deals go through, it would likely mark the end of Intel as an independent company (although it may continue as a subsidiary or under a different brand name). In such a case, shareholders are likely to benefit from a decent return on shares that have been on a downward trajectory for some time. For Intel's board of directors, this might be the safest bet if their main goal is to ensure shareholder value.

For Taiwan, TSMC is a critical national security asset. The country, which China considers a part of its territory, lacks desirable natural resources and has a military not strong enough to deter Chinese invasion. However, it does have a world-leading chip manufacturing industry that the global economy depends on for smartphones, computers, data centers, and other products. Whoever controls the chips controls the world, and Taiwan understands this well. Its industry is its best defense against Chinese invasion, as no Western country wants China to control the global chip supply.

In this respect, TSMC has a clear interest in strengthening its position and ties with the U.S. It is already doing this by building a chip manufacturing plant in Phoenix, Arizona, with a $65 billion investment (including a $6.6 billion U.S. government grant). The acquisition of Intel’s manufacturing operations, particularly in the U.S., would strengthen TSMC's ties with the Trump administration and further the administration's interest in preventing Chinese control over the U.S. chip manufacturing system. Additionally, the deal would help TSMC rapidly expand its manufacturing capacity and solidify its dominance in the sector by eliminating a potential competitor.

Although no tech giants currently want to become chip manufacturers themselves, they certainly have an interest in holding stakes in such manufacturers. Apple, for example, has deep control over its entire supply chain and would likely want a stake in any chip manufacturing company. This would ensure it has a seat at the table and some influence over the direction of chip production. Similarly, for Nvidia, having a stake in the manufacturer could secure preferential treatment in chip production, helping it maintain its leadership position in the market and making it harder for competitors to gain a foothold.

Broadcom, one of the most successful chip companies, largely focuses on chips for networking, communications, storage, and industrial applications. It doesn’t have significant involvement in CPUs or GPUs, which are the foundation of modern AI processors. Acquiring Intel’s design operations would allow Broadcom to expand its product offerings and compete with Nvidia. While Intel has faced difficulties in developing AI processors, it’s possible that under new management, the company could quickly overcome these obstacles and present a comprehensive solution to the market. This is likely the reasoning behind Broadcom’s interest.

The deal and Israel

Intel is one of the largest employers in Israel, and the country plays a central role in the company’s operations, with its large factory in Kiryat Gat and significant R&D activities responsible for the development of Intel’s processors. Any deal would bring uncertainty to these local operations, likely resulting in layoffs and cutbacks. However, it can be reasonably assumed that Intel’s operations in Israel will not disappear completely in any scenario.

Intel has already invested billions of dollars in its existing factories and the construction of a new plant in Kiryat Gat. This investment supports advanced production facilities and quality products. TSMC has no economic interest in halting this activity, and is likely to integrate the plant into its existing production system. However, if TSMC identifies duplication in the factory’s operations in Israel, it might decide to close the plant or sell its assets.

Less uncertainty surrounds Intel’s R&D activities in Israel. The country has become a global center for chip development, not only because of Intel but also due to local R&D centers from Apple and Nvidia. Broadcom already has significant R&D operations in Israel, making it likely that the company would want to preserve Intel’s chip development activities and integrate them into its business strategy. It makes no sense for Broadcom to acquire such an important part of Intel’s operations only to discard it.