After losing almost 90% of its value: Is Selina on its way to becoming the next WeWork?

The Israeli-founded company, which completed its IPO in 2022 at a valuation of $1.2 billion, currently has a market cap of just $130 million

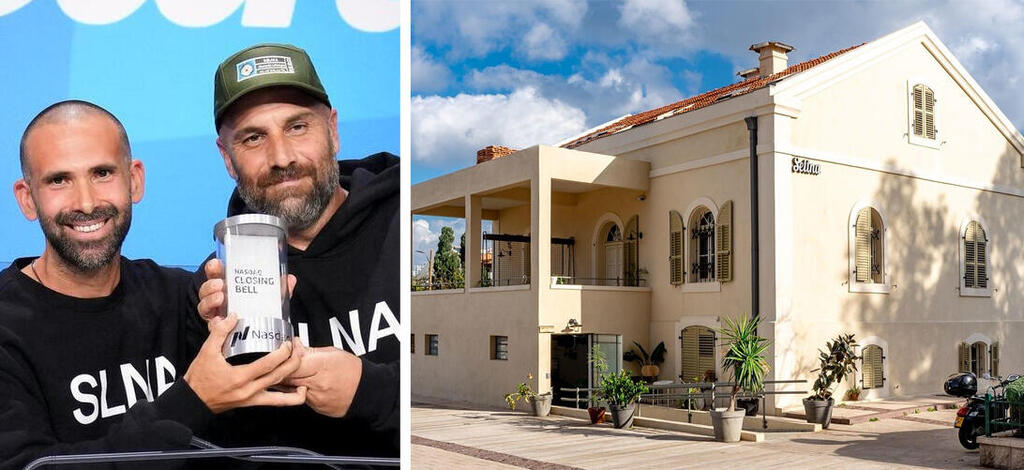

Hospitality company Selina published its first full financial reports - and the investing public was not impressed. The company, which was founded in 2015 by Daniel Rudasevski and Rafael Museri and completed its SPAC merger at the end of October 2022 at a valuation of $1.2 billion, currently has a market cap of just $130 million, a drop of almost 90%..

Interest in the company's stock is low and trading volume has been quite negligible for almost five months. It's hard to blame investors, even though the company shows an increase in revenues, a deliberate slowdown in growth and a reduction in salary costs, its results are still not impressive.

Selina revealed that it had accumulated a deficit of $725 million despite revenues of $184 million, a 98% increase compared to 2021. The company said its occupancy rate increased from 33% the previous year to 47%. Nevertheless, it registered a negative cash flow of $24 million and a bottom line of loss that increased from $185 million the previous year to $198 million.

The company did not provide a profit forecast for the coming year, but in a presentation to investors it stated that its goal is to reach a positive cash flow at the end of the year. In fact, Selina announced, in an uncharacteristic move for a hotel chain but one quite popular among tech companies, that it may never achieve profitability.

The company also reported that there were issues with its internal audit in regard to the company's financial statements for the years 2020-2022. Selina said that it did not have a sufficient level of regulatory procedures to detect errors that could be important, especially in relation to complex accounting matters, in particular tax accounting, share-based compensation accounting and derivative accounting. In addition, in 2021 it identified a substantial issue related to the lack of internal controls to prevent a cybersecurity breach. The company noted that it has not yet addressed all of the issues.

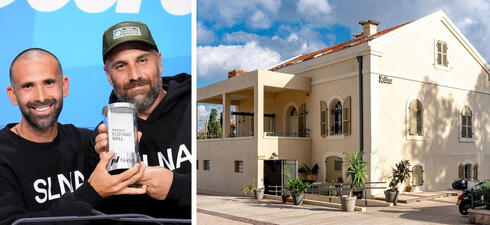

The main problem with Selina is rooted in its business model. The company presents itself as one of the world's largest operators of "lifestyle experiential hotels for millennials and Gen-Z.” It leads the sector because it invented it. Since its establishment in 2015 and until today, it has opened 118 hotels (or hostels) around the world. Its strategy includes finding cheap and unsuccessful sites, renovating them within a few months and with financing from local partners, and operating them at an accessible price that includes work spaces, convenient transportation and entertainment. The goal is to serve the so-called digital nomads. "We are democratizing the world of rooms," Rudasevski said.

Selina does not own most of its properties except for two. The company's greatest asset is the brand it has built. The major costs that lead Selina to ongoing losses since its establishment are from operating the hotels.

Here a question emerges: why does a hotel chain whose fixed expenses have generated only losses since its establishment choose global growth and expansion as a business strategy? In the hotel sector, there is no advantage to size, so there is no reason not to act in a more conservative and measured manner. Even Selina notes in its report that aggressive growth is also a risk factor.

One explanation is technology, which Selina says is responsible for "reducing costs,” among other things. It also allows us to think of Selina as a growth company, rather than a hotel chain. The technology "developed by the company" mainly includes an application through which you can book rooms, check-in and order transportation, as well as a system that analyzes the usage of spaces and can set timers for lighting, heating, air conditioning and water in order to reduce costs.

Selina's reports are very reminiscent of WeWork's reports, whose founder Adam Neumann is a large investor in the company (9%). In both cases, the same issues are evident, including defining an innovative segment for the younger generation and leading it, and using technology to explain why a company that operates in a traditional field like real estate allows itself to behave like a tech company and registers losses all along the way.

Like WeWork, Selina also invented a new index through which to measure the company's performance. In the case of Selina: TRevPOB or total revenue per bed occupancy. The company explains that this index is more relevant than standard occupancy because the rooms they offer can be converted, and therefore a new index is required to more accurately express the financial performance. However, the need for the index is confusing, since there is no explanation in the company's reports as to the mechanism used to convert rooms or its frequency.

What's more, Selina's business, as it itself defines it, is renting a "room" for a limited period, as they do in a hotel. The use of the room is customary because it defines the occupancy of the hotel in the strictest way. Selina offers private, double family and shared rooms, and therefore bed occupancy does not seem like an accurate measure of its activity. Does a hotel that rents a room to a family indicate in its financial reports that the family requested an extra bed?

The comparison to WeWork is warranted when it comes to their style, but when it comes to the company's business, it should be compared to hostel chains or hotels, although Selina tries to differentiate itself from them.

In practice, Selina is part of a traditional industry. If you look at it as such, the company's performance reflects a problem. Although there are not many public hostel chains to compare to, there is a large one, Hostelworld, established in 1999. Both companies offer varying room models (private and shared), but only Selina thought it necessary to define it in a sophisticated new way. Also only one of the two, Hostelworld, chose a conservative growth strategy and issued its shares to the public in a healthy way (in 2015), while showing a consistent net profit.

GreenTree is another chain of guest houses that went public in 2018. Like Hostelworld, GreenTree did it quite traditionally. Although in the prospectus for its IPO it defined itself as a "growth" company, it entered the New York Stock Exchange with a positive bottom line and a history of net profit, which it maintained until the outbreak of the pandemic. Atour Lifestyle, a Chinese chain of hotels established in 2012 which went public last November, ended last year with a net profit of $14 million.

These three hospitality companies which all went public in recent years demonstrate one small thing: net profit is not a dirty word, conservative growth is not a bad thing, and there is no need to emphasize innovation or technology. You can simply build a better product.