Opinion

In the city of slaughter in the Jewish state

On a tour of Kibbutz Nir Oz, the site of one of the worst massacres on October 7th, CTech’s Ariela Karmel was reminded of Israeli National Poet Hayim Nahman Bialik’s “In The City of Slaughter” about the 1903 Kishinev pogrom. Today, on Yom Hashoah, in Nir Oz, in the Jewish state, the same horrors are still best articulated by Bialik - by a poet eulogizing a pogrom.

You can’t help but be struck by the ordinariness of Nir Oz. It looks like any other kibbutz you may have been to, or village or small town. The homes are simple and modest. Colorful murals decorate the bomb shelters, the gardens and the children’s playgrounds (which also function as bomb shelters).

There are few streets built for cars; bikes are the main mode of transportation and the landscape is filled with the incinerated skeletons of bicycles. Most of the houses are connected by small lanes, for neighbors and children of the kibbutz to walk freely through each other’s homes - the same lanes that would be used by their murderers.

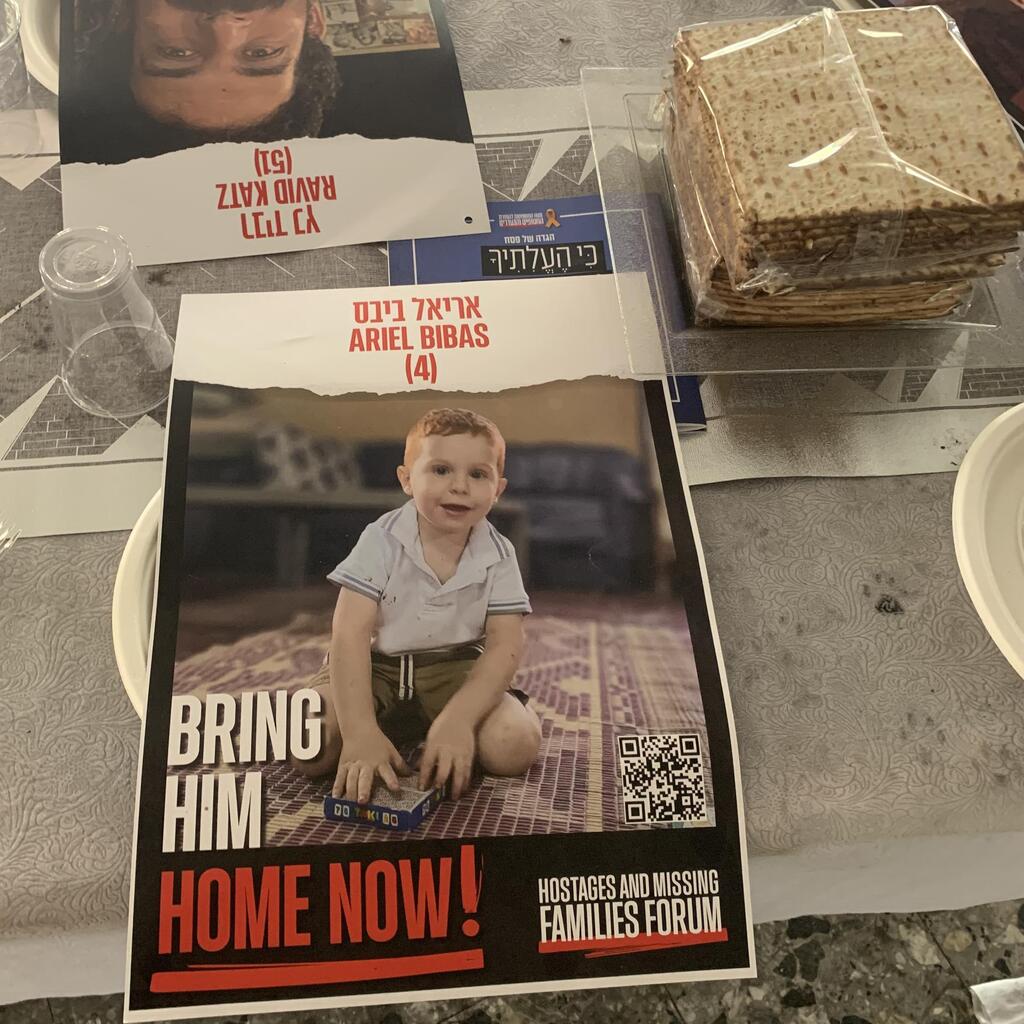

For six months, time has stood still at Nir Oz; an occasional sukkah remains standing as a corporeal timestamp. It’s mostly uninhabited, quiet and peaceful, as a graveyard should be, silent but for the birdsong and the wind rustling through the trees. But the specter of death is immutable. This is, after all, the site of an ongoing, indefinite, never-ending massacre as 36 members of the once 400-person community remain in captivity. Their faces are papered across the kibbutz, on the walls of their homes from which they were taken, at place settings in the communal dining hall [floors covered in glass and reeking of death] for the most disquieting makeshift seder held in decades.

Walking through the kibbutz feels disrespectful, even transgressive. You’re walking uninvited as tourists, as spectators, through the ruins of the homes of those who fled in terror, were brutally murdered, or stolen and remain languishing in Gaza.

Some of the houses are burned beyond recognition, their charred bones all that remain, windows and bullet holes like gaping wounds; in place of floorboards, you stumble through ashes. Houses that weren’t burned were destroyed and looted by the marauding hordes who descended upon the kibbutz in a frenzy, the belongings of its residents ruined and in tatters.

For no discernible reason, some things were left intact; a lone painting, leaning against a wall amid an array of unrelated objects cast into the yard; blue wind chimes with white flowers hanging from the rafters of a house which was otherwise burned black. Most likely they were of little use or interest to the thieves pilfering the treasures of Nir Oz's residents; unlikely that there were art or antique enthusiasts present in the mob.

There is a glaring juxtaposition between the post-apocalyptic scene and the awful beauty of the surroundings. Nir Oz, like most kibbutzim, especially in the Western Negev, remains beautiful. It’s very green and verdant, filled with palm trees, red and purple flowers, and hydrangea bushes. Plants continue to grow amid the carnage, flowers sprouting amid the rubble. But resist the urge to interpret this as some vulgar metaphor for rebirth or hope amid the carnage - it’s not.

If anything it mocks us. As if to say, 'yes, here too; in this community, in this state whose raison d'être is to prevent such mindless savagery.'

Hayim Nahman Bialik, Israel’s national poet, wrote “In The City of Slaughter” about the 1903 Kishinev pogrom, a scene of mass murder and rape against the Jews of Kishinev, a name which remains synonymous with slaughter to this day. It was a watershed moment for Bialik who concluded that a state was the only sure safeguard against the world’s insatiable desire to murder Jews.

He certainly never expected that such an event would be repeated in this very state. And one can't help but wonder how he would have despaired to see that today, on Yom Hashoah, in Nir Oz, in the Jewish state, the same horrors which beggar belief and defy description are still best articulated by him, in the familiar lamentation echoing throughout Jewish history of a poet eulogizing a pogrom.

“Arise and go now to the city of slaughter;

Into its courtyard wind thy way;

There with thine own hand touch, and with the eyes of thine head,

Behold on tree, on stone, on fence, on mural clay,

The spattered blood and dried brains of the dead.

Proceed thence to the ruins, the split walls reach,

Where wider grows the hollow, and greater grows the breach;

Pass over the shattered hearth, attain the broken wall

Whose burnt and barren brick, whose charred stones reveal,

The open mouths of such wounds, that no mending

Shall ever mend, nor healing ever heal.”