Why robots aren’t taking over jobs yet: the realities behind the hype

The much-anticipated robotic revolution in the workforce hasn't fully materialized, but will it soon?

From the moment the concept of robots was born, they have been assigned ambitious and often fantastical tasks. Perhaps the first infamously absurd task was the U.S. Department of Defense’s mechanical elephant - an American military project that sought to replicate a mechanized version of the elephants used by Viet Cong soldiers in the Vietnam War to transport food and ammunition through areas inaccessible to jeeps and helicopters. The idea was quietly buried by the agency out of fear of ridicule if the news got out.

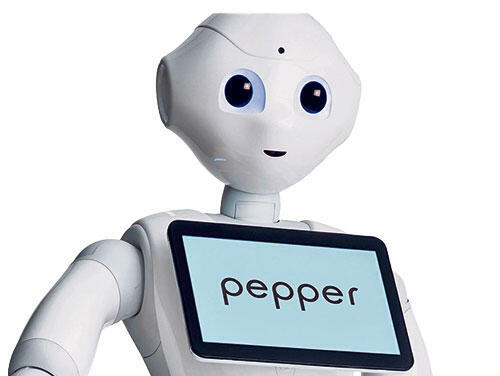

Fast forward to 2014, and the conversation sharply shifted from Terminator-style fantasies to life-changing applications. The image of robots quickly evolved from metal beings to white plastic figures with constant smiles, wheels, and screens on their chests. SoftBank introduced Pepper to the world as "the world's first personal robot that reads emotions," though it was almost incapable of doing anything. Pepper was supposed to serve as a solution to the shortage of elderly care staff, overseeing medication intake, and as a companion.

From that point on, the idea that we need to prepare for the era of robots began to take root. Google purchased five different robotics companies that year, the UK government announced that they would invest tens of millions of pounds in the development of therapeutic robots, and Japan declared that every nursing home patient would receive a robot. Newspapers began sounding the alarm. "Welcome to the dawn of the age of robots," declared headlines in "The Washington Post"; "Age of Companion Robots," wrote "Forbes"; "Will you lose your job to a robot?" asked "The New York Times," to which "The Guardian" responded: "Robots will destroy our jobs - and we’re not ready for it."

Tax on robots

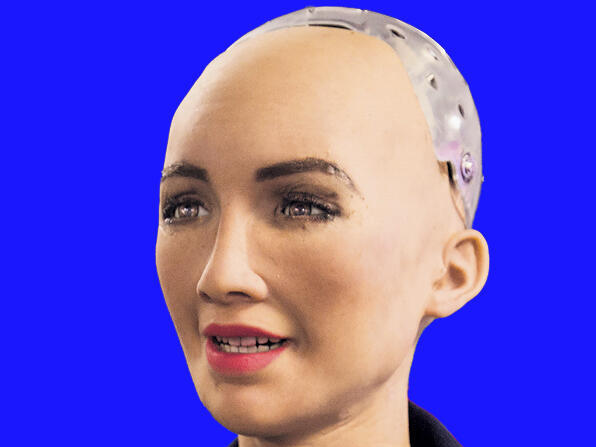

In 2017, after the White House’s Council of Economic Advisers estimated that a significant percentage of jobs in the labor market would be made redundant due to robots, Bill Gates proposed a tax on robots. The idea was negatively received by economists and Silicon Valley insiders who deemed it terrible and began debating tax issues, all while robots were far from being capable of executing such a massive replacement project. That same year, Saudi Arabia granted citizenship to the social robot "Sophia."

In practice, however, there are almost no robots in nursing homes, not in the UK or Japan, either because robots are expensive or simply because they don’t do much. That’s how it goes: the tech industry is great at selling stories to the public, often joined by consulting firms, banks, and investment funds that stoke the imagination with predictions of how robots will replace us and dramatically change the job market. But in practice, this has not been the case.

In 2020, six years after the hype began, one MIT study put things in perspective: maybe the Boston Dynamics robot can do a cartwheel, but it can’t do office work. We can relax, at least for now, because industries are adopting robots to varying degrees, and they are primarily present in the automotive industry and in replacing various manual labor jobs in fields, factories, and warehouses, not at home. The most successful robotics companies today produce less anxiety-inducing products, like the iRobot vacuum cleaner, or ABB’s successful line of robotic arms used in the automotive, medical, and warehouse industries.

Not that the market has stalled: "The global market for humanoid robots could reach $38 billion by 2035," Goldman Sachs estimated in a February report that garnered enthusiastic headlines. And yet, the use of robots, especially humanoids which promise everyday applications for private users, is still limited and mainly amounts to vacuum cleaners, floor scrubbers, and pool cleaners.

Humanoid robots - the main trend in robotics today - promise much more than they can deliver, are in very early development stages, and carry astronomical price tags, reaching at least tens of thousands and up to several million dollars. For example, Hello Robot developed Stretch, a column on wheels with an arm that can lift objects remotely, hold a phone, brush hair, or take a picture. This could certainly be useful for people with various disabilities, and it can be yours for the relatively modest price of $18,000.

Why can't a robot fold laundry?

How do machines manage to pass the bar or medical exams but fail at simple tasks like folding laundry? Hans Moravec, a robotics expert at Carnegie Mellon University, identified this paradox back in the 1980s: What is difficult for humans to do is easy for machines, and what is easy for humans is hard for machines. A robot can defeat a Chess grandmaster or replicate Da Vinci’s sculpting skills by elegantly chiseling marble, but it struggles to tie shoelaces.

The reason, Moravec explained, is that things we do as a matter of course, without much thought, using spatial perceptions, vision, hearing, and innate intuition, are difficult to reverse-engineer. "It is comparatively easy to make computers exhibit adult-level performance on intelligence tests or playing checkers," he wrote, "and difficult or impossible to give them the skills of a one-year-old when it comes to perception and mobility." For example, even when robots succeed in picking up objects without dropping them, they are usually controlled by a human.

The reason for this counterintuitive relationship is that the simpler a human skill, the older it is evolutionarily. In other words, it’s a skill that has undergone more optimization processes. Mathematical or abstract thinking, which is a relatively recent skill compared to sensory skills, has undergone fewer optimization processes, requires more "computing power," and is therefore easier for computers to perform.

As Moravec wrote: "We should expect the difficulty of reverse-engineering any human skill to be roughly proportional to the amount of time that skill has been evolving in animals." This means ancient skills that seem effortless, such as skipping a step while jumping or picking a flower gently, are difficult to compute, while skills that require effort, like solving a math problem or playing chess, are less difficult to compute.

And what about emotional intelligence and the promise that robots will be able to care for the elderly and children, alleviate loneliness, and help reduce the burden on social services? There is no evidence that robots are capable of this. Studies actually suggest that they may work only with assistance from staff who know the patients, and many of the patients treated robots as they would treat an iPad.

Until there’s a solution to Moravec’s paradox, robots will thrive primarily where they are of little interest to the general public - in warehouses, operating rooms, and as vacuum cleaners. So, don’t expect an Amazon delivery robot any time soon, or a robot acting as a hotel receptionist or the server at a restaurant.

First published: 11:16, 26.08.24