Analysis

Why the Fed's got it wrong with interest hikes

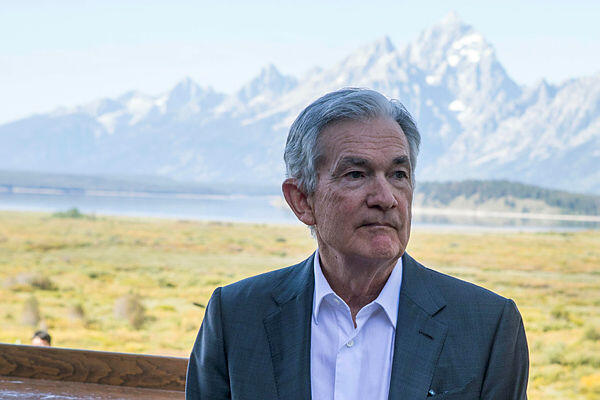

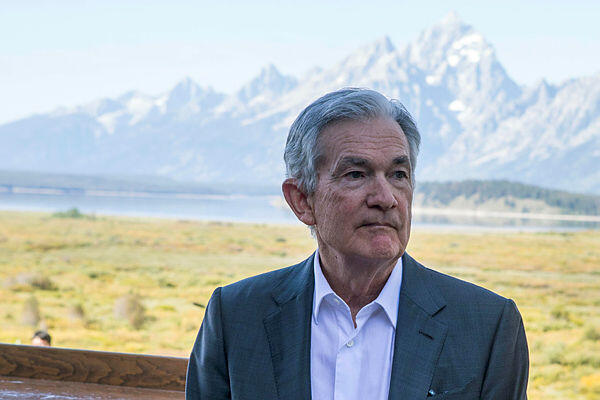

"We are ready to raise interest rates further if necessary," Jerome Powell said in his speech in Jackson Hole. The Fed's goal is to lower inflation to 2%, at the expense of the suffering public

In his annual speech at Jackson Hole, closely monitored by the banking system, Jerome Powell, the Chairman of the Federal Reserve, put all doubts to rest: the Fed's objective is steadfast - to bring inflation down to a target of 2%. He commenced his speech by stating that he wouldn't introduce anything new, immediately shifting to a hawkish tone: "Although inflation has come down from its peak - a welcome development - it remains too high," he said. "We are ready to raise interest rates further if necessary, and intend to hold policy at a restrictive level until we are sure that inflation is sustainably moving down towards our goal." Powell ended his speech this year the same way he ended it the year before: "We're going to keep at it until we get the job done."

The annual Jackson Hole Conference of the Federal Reserve Bank of Kansas City, held in Wyoming, represents a significant event in the banking world. Attendance is reserved for senior officials of central banks. The chairman's address is the only one broadcast to the general public and lasts under two minutes. Typically, the current chairman outlines the monetary policy for the upcoming months, attracting viewers, market participants, analysts, and others. This year, Powell's remarks, indicating a continued strategic approach from the prior year, did not trigger an aggressive market reaction. The Fed will proceed "with caution," he explained, attempting to convey some openness by acknowledging their vigilance regarding the possibility of the economy not cooling down as anticipated.

In July, the Fed raised the interest rate for the 11th time in 17 months, reaching 5.5%, the highest level in 22 years. These assertive hikes significantly impacted the housing market, propelling mortgage rates to a two-decade peak and causing a steep decline in home sales. However, the hikes yielded positive outcomes as well. Over the past 12 months, following the peak of 9.1% inflation in March 2022, inflation in the United States has been on a declining trajectory. Although it slightly rose to 3.2% in July, following a 3% rate in June, the same month witnessed a modest drop to 4.3% in core inflation (excluding food and energy). Furthermore, at the beginning of the month, the US Department of Labor announced a 3.7% increase in labor productivity during the second quarter of the year, following five consecutive quarters of decline.

This momentum has triggered a public debate among senior Fed officials in recent weeks regarding the aggressiveness of interest rate hikes. Some have advocated maintaining the current levels rather than making further adjustments. Some even suggested revising the Fed's inflation targets to raise them to 3%. In his speech, Powell aimed to present the intricate discourse: "Doing too little could allow inflation above the target to become established," he said, "Doing too much could also cause unnecessary damage to the economy." The words continued the trend of ambiguity and uncertainty: "Additional evidence of persistently above-trend growth could put further progress on inflation at risk and could warrant further tightening of monetary policy,” he said, emphasizing: "We are prepared to raise rates further if appropriate, and intend to hold policy at a restrictive level until we are confident that inflation is moving sustainably down toward our objective." But he also made a reservation and noted that "We are navigating by the stars under cloudy skies...Considering where we have come, we will proceed carefully as we decide whether to tighten further or, instead, to hold the policy rate constant and await further data."

A decrease in interest rates is unlikely before 2024

In September, the Fed is expected to announce its next interest rate decision. Current market estimates suggest no further hikes at this point, though another increase later in the year remains plausible. Those anticipating a decline in interest rates may need to wait until possibly 2024. Powell cited better-than-expected GDP growth and robust consumer spending as indicators potentially necessitating additional interest rate hikes. He also highlighted the strength of the labor market, even though the rate hikes cooled it down and curbed consumer spending.

In practice, the U.S. unemployment rate stands at 3.6%, nearing historic lows, maintaining the same rate since the Federal Reserve began its aggressive interest rate hikes. Additionally, the rate hikes have not notably impacted job seekers' or employers' expectations. Data from a consumer expectations survey at the beginning of the month indicated a year-over-year wage increase of 11.8% for job seekers, reaching $67,000 annually - the largest jump since 2014. Simultaneously, the average full-time salary for job seekers rose by 14% in July compared to the previous year, reaching a record $69,500. Against this backdrop, the U.S. is witnessing its most significant surge in labor unionization since the 1980s. Negotiations for collective agreements and improved employment terms are underway across sectors such as hospitality, transportation, education, medicine, and restaurants.

The stability of the labor market starkly contrasts with alarmist warnings and dire predictions from some of the prominent voices in the economy. As highlighted by Barron's, former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers recently asserted that "five years of unemployment above 5%" would be required to control inflation, cautioning that all data points towards a recession. Frederick Mishkin, a former member of the Fed's Board of Governors, echoed similar warnings, stating, "The bottom line is that a recession is probably in the cards." Jason Forman, the former chairman of the White House Economic Council, noted, "To bring the inflation rate to the Fed's target of 2% would necessitate an average unemployment rate of approximately 6.5% in 2023 and 2024."

Related articles:

- Fed chairman Powell’s revolution has major ramifications for Israel’s monetary policy

- Former World Bank Chief Economist: "Inflation is still sticky. The test of the Fed's determination is still ahead of us"

- "Anyone who believes that central banks should halt interest rate hikes lacks an understanding of history"

Changing perceptions

In curbing inflation, all, including Powell and the Fed's approach, seem willing to tolerate high unemployment - or the suffering of the American public, particularly the lower classes. This method of managing inflation, however, is far from grounded in reality and was initially introduced by Paul Volcker, who assumed the Fed's chairmanship in 1979. "The standard of living of the average American needs to decline," he stated, aiming to contain the "great inflation" of that era. In June, progressive economist James Galbraith noted that subjecting the American public to suffering isn't the sole way to address inflation: "In turbulent and uncertain times," he wrote, "increased margins serve as a hedge against cost uncertainties. A climate of 'get what you can, when you can' develops. The result is a cycle of rising prices, escalating costs, and rising prices again — with wages consistently lagging behind."

According to economist Elizabeth Weber, inflicting hardship on the public is unnecessary; rather, governmental intervention is needed to rectify the situation. She suggests that price controls could disrupt the current pattern. This isn't a novel concept; between 1942-1946, Roosevelt led the Office of Price Administration (OPA), effectively curbing inflation during that period. Unfortunately, this experiment ended in 1946, and since then, the responsibility for managing inflation has rested solely with central banks. They are prepared to endure elevated unemployment to achieve a fixed inflation target, the appropriateness of which remains debatable.

First published: 16:21, 27.08.23