Analysis

Don’t count on advertisers to end hate speech on social media

Don't expect Unilever and Coca-Cola to hold hands and sing kumbaya together with the liberals. The history of the relationship between advertisers and social media platforms proves they have their own agenda

The immediate reaction to Unilever's announcement was a sharp drop in the share price of the digital giants, including Facebook, Google, Twitter and Amazon. The investors are naturally concerned that this ban could expand to include more large advertisers and hurt the income of these social platforms, resulting in a loss in value over the coming quarters. This is the moment the socio-economic commentators have been waiting for, with the financial pressure by the big advertisers finally accomplishing what governments couldn't achieve in the fight against online hate speech. An advertising ban is the most effective tool that can be turned against a media platform as it results in double damage, harming it both from a financial and reputation standpoint.

Unilever is pulling its advertising from Facebook, Twitter and Instagram until the end of the year. Photo: Unilever

Unilever is pulling its advertising from Facebook, Twitter and Instagram until the end of the year. Photo: Unilever

Does the ban on digital platforms truly come from a real and genuine belief in the change American society requires or is this just a case of cynical advertisers opportunistically riding the hypocritical and purist wave that characterizes some of the American corporations? Is a true ideological battle underway or is this no more than a power move to force the platforms to lower their prices during an economic crisis?

What happened over the past week that prompted Unilever, Verizon and North Face to act? What did they come to understand regarding the problems in U.S. society which they didn't already know two or three weeks ago, or six months ago when it comes to the conduct of Facebook, Google or Twitter?

This isn't the first or even second time that Unilever has threatened social media platforms with an advertising ban. Back in 2017 the heads of the company already expressed doubts regarding the effectiveness of online advertising. In June 2017, Keith Weed, Unilever's chief marketing and communications officer, said that he no longer believes in online advertising seeing no proof of its effectiveness and the company announced that it would be diverting budgets from Facebook and Google to more effective platforms. Weed explained that after a meeting with Snap and Twitter, who were at the time the rising rivals of Facebook and Google, that he expects the digital companies to improve their standard of reporting and only then will they “get more of my ad dollars." Weed also demanded that the advertisers adopt a more fastidious attitude regarding the calculation of what they are paying social media platforms as they can’t really be trusted to determine whether the campaign was successful or not.

Six months later, in February 2018, Weed continued his assault on Facebook and Google, but turned his focus from technological and professional claims to ideological arguments. Weed said at the IAB Annual Leadership Meeting conference in California that Unilever will not be investing in a platform that doesn't protect children and promotes hate and anger. He added that Unilever will prioritize investing "only in responsible platforms that are committed to creating a positive impact in society."

Coca-Cola, which spends $22 million a year on social media advertising, also made the most of the opportunity and announced over the weekend that it is suspending advertising on social platforms for 30 days, but will not be joining the official campaign. The drinks maker's chairman and CEO James Quincey said the company would use the pause to "reassess our advertising policies to determine whether revisions are needed" and demanded greater "accountability and transparency" from social media firms.

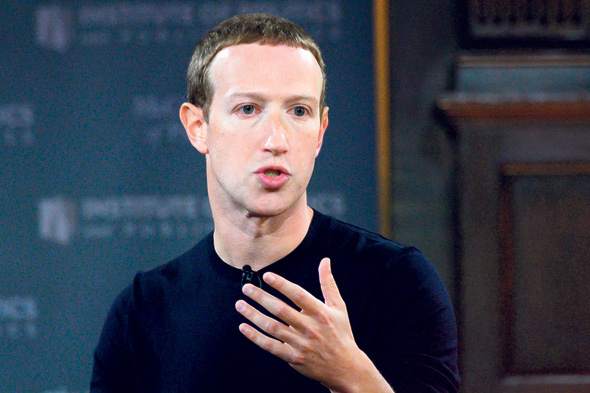

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Photo: AFP

Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg. Photo: AFP In November 2018, Coca-Cola made a similar move, albeit of a far less combative nature and far more marketing focused, when it deleted all its content from its Facebook, Twitter and Instagram feeds. In honor of World Kindness Day, the brand's feeds went dark on November 13, and were later flooded with almost 100 pieces of in-house content created by four street artists aimed at presenting a more optimistic and inspiring cohesive voice and visual language for the company. The financial connection between Facebook and Coca-Cola goes far beyond just advertising, with the two sharing several shareholders, including Blackrock, Vanguard, Fidelity and Capital Research.

2020 is a year of an economic crisis. The Covid-19 pandemic isn't just transforming the lives of hundreds of millions of people across the world, but it is also affecting their consumption patterns. Physical limitations, lockdowns and growing unemployment is changing buying habits and as a result also the ability of consumer corporations to create the same income and profit which their shareholders have grown accustomed to. Streamlining has become the name of the game for corporations in 2020. While mass firings could hurt the company's image, pulling advertising funds from Facebook with the excuse of creating a "safe digital space" can only improve their image.

Unilever can afford to cut a few million dollars from the $40 million it spends on social media advertising a year or invest them in advertising in other media outlets the way it promised to. On the other hand, this economic pressure could have a positive impact on the company from an unexpected source, with ad prices on social networks potentially dropping even further. For companies that invest millions in advertising, this could prove to be a significant sum.

The stance taken by Unilever against the violent and polarizing tone running rampant on social media is positive and resulted in Zuckerberg immediately promising to take action against hate speech. But history has shown that the relationship between Facebook and its big advertisers has a regular pattern: every time that there are differences between the sides, the advertisers raise their voices and speak out against Facebook. Neither Facebook's senior management nor its investors want to fall out with the advertisers, so Zuckerberg and co. are quick to apologize and promise to straighten matters out. The advertiser earns the image of a freedom and human rights fighter (and perhaps also a cheaper advertising rate) while Facebook puts out the fire. At least until the next time.